On Dec. 18, 2012, in Durham, North Carolina, police officer Kelly Stewart pulled over Carlos Antonio Riley for a routine traffic stop. What happened next is a matter of intense dispute. Riley, who is black, says the officer racially profiled him then attacked him. Stewart, who is also black, says Riley engaged him in a violent, physical struggle. The encounter ended when Stewart accidentally shot himself in the leg with his firearm. Soon after, the police department logged the gun’s discharge: “1 shot fired by officer.”

District Attorney Roger Echols, working closely with the police department, then launched a criminal case against Riley—claiming that Riley shot Stewart with Stewart’s gun. The DA kept mounds of evidence away from the jury that proved Stewart shot himself. And he pressed his case against Riley all the way to trial, where Stewart testified, under oath, that he did not shoot his gun.

Earlier this month, a jury acquitted Riley of shooting Stewart, bringing a just end to a deeply troubling story. During the trial, defense attorney Alex Charns repeatedly described the prosecution’s strategy as “a shell game, a cover up, and a railroad.” Examining the evidence, it is nearly impossible to come to any other conclusion.

From the start, Stewart’s attempt to detain Riley looked like bad policing. Stewart was driving an unmarked vehicle and dressed in plainclothes when he pulled Riley over—for “fishtailing” down the road, he alleges. Riley says he was pulled over for driving while black. Stewart claims the car slid forward during the stop, and he dove in to grab the emergency brake. Riley claims the officer pulled out his gun and screamed, “Get back, I’m gonna fucking shoot you!” At one point, Stewart claimed he was standing outside the car during the fight. Later, he claimed Riley wrestled him onto his back in the passenger seat then climbed on top of him.

Both men agree about what happened at the end of the encounter: One bullet was fired from Stewart’s gun into Stewart’s leg. The officer made a quick recovery. Riley was sent to prison.

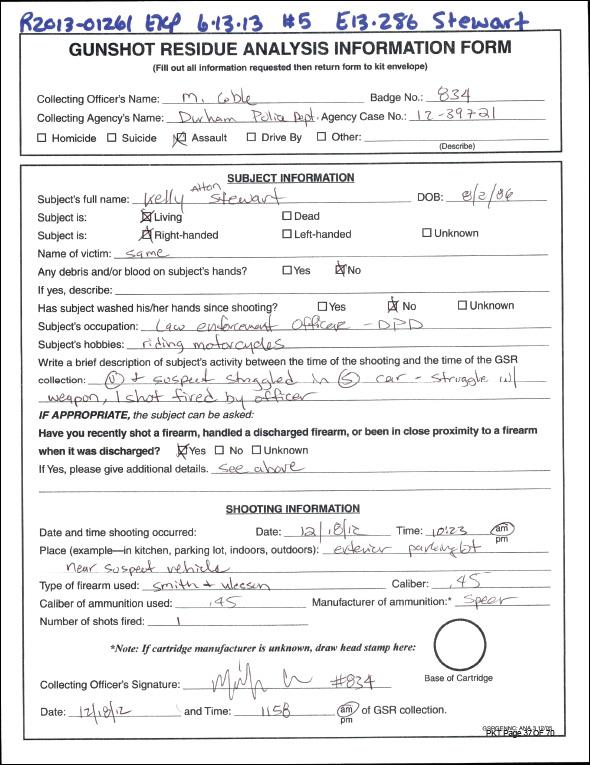

It’s not clear when the police department decided to assert that Riley shot Stewart, bringing in the DA to prosecute what had theretofore been treated as an accident. But it certainly didn’t happen immediately. Ninety-five minutes after the shooting, an official at the department filled out a gunshot residue analysis information form, which plainly declared that the officer—not the suspect—fired the shot. On the day of the shooting, Stewart appears to have acknowledged that he fired his own gun.

Document via Durham Police Department

But by the time the case went to trial, Stewart’s story had changed, and no officers came forward to contradict it. Now Stewart alleged that his finger was off the trigger when the gun went off. In his new memory of the altercation, Stewart testified that Riley brutally beat him after he pulled the car’s emergency brake. (An emergency medical services witness said Stewart had no injuries that would indicate a physical assault—no bruising, cuts, or blood.) Stewart alleged that Riley then grasped the muzzle of his gun, turned it toward the officer, and fired it.

If that were true, Riley’s hand would have burns from grasping the hot muzzle of a smoking gun. Riley had no such burns.

Stewart’s story had other problems. The officer claimed he pulled over Riley for swerving excessively—yet, oddly, he declined to call the stop in to police communications, in violation of department policy. (Charns speculates that Stewart did not want to boost his traffic-stop statistics for blacks, which were already uncomfortably high.) Stewart also said he had to dive into Riley’s car to pull the emergency brake—but the brake’s handle is quite large and seemingly accessible from outside the driver’s door. Finally, Stewart claims Riley savagely pinned him down on his back in the passenger seat. This, however, is physically improbable. Riley’s Nissan is tiny, with minimal room to maneuver. Stewart alleges that he jumped into the car face-first, somehow wound up on his back in the passenger’s seat seconds later. Charns told jurors that Stewart would have to be a “shape shifter” to accomplish this feat.

The prosecution kept all inconvenient evidence—including the critical gunshot report—out of the trial. That strategy forced the defense to make a tough decision. Under North Carolina law, the defense is allowed to make the first and last closing arguments. But it loses that right if it introduces its own evidence. Charns weighed the benefit of an impassioned closing argument against the dry but revealing gunshot analysis form. He decided he would rather send the jury into deliberations after hearing his vehement closing plea.

As Charns prepared for trial, he received an unsettling surprise. Prosecutors asked for an in-chambers, off-the-record meeting—and asked the judge to remove Charns as Riley’s counsel. Charns, they claimed, was insufficiently informed about “criminal rules and procedures.” This extremely unusual request came as a shock to Charns, a renowned attorney with 32 years of experience who specializes in police misconduct cases and criminal trials. Charns, who was appointed to the case by a public defender specifically because of his stellar qualifications, demanded that the discussion be moved to open court and put on the record. The judge denied the prosecution’s request in open court before the trial began.

Riley was found not guilty of assaulting Stewart by a jury of 10 men and two women. After the jury announced its verdict, Charns asked the judge to sanction the prosecution for its alleged misconduct. The judge denied the request.

Durham Police Chief Jose L. Lopez Sr. released a statement on behalf of the Durham Police Department following Riley’s acquittal, stating that “we’re disappointed with today’s verdict.” The department also clarified that it “has no further comment on this case.”

Although Riley has been acquitted of shooting Stewart, he will not walk free. Because Riley fled the scene with Stewart’s gun, the jury convicted him of robbery. (Riley is appealing this conviction.) Moreover, Riley previously pleaded guilty to possession of a firearm by a felon in a separate federal prosecution centered around the same incident. (The firearm he possessed was Stewart’s gun.) For that crime, Riley was sentenced to an unexpectedly severe 10 years in prison—the maximum sentence he could have received for the crime.

Shortly after I interviewed Charns, he sent me an email telling me that someone called him, claiming to be Mark Joseph Stern, asking about the Riley case.

“Please let me know if this was in fact not you who called,” he wrote.

I responded, confirming that it was I who called, but that I understood his concern.

“You can never be too sure,” I wrote.

He responded immediately.

“Not the way this case went down.”