Just before the Supreme Court closed out its term on Monday, it condemned a man to death. Richard Jordan, who has been on Mississippi’s death row for 38 years, had asked the justices to reconsider an appeals court’s ruling that blocked his access to the courts. Without explanation, they declined. The justices’ refusal to examine Jordan’s case clears the way for his execution. It may be remembered as their most gallingly unjust decision this term.

Jordan’s saga began in 1976, when Jackson County Assistant District Attorney Joe Sam Owen prosecuted him for the murder of Edwina Marter. Under Mississippi law at the time, a capital murder conviction resulted in an automatic sentence of death. But later that same year, the Supreme Court held that automatic death sentences were “cruel and unusual,” in violation of the Eighth Amendment.

The trial court gave Jordan a new trial. Owen once again served as prosecutor. During his closing argument, Owen told the jury that “each of you have to determine what is an aggravating circumstance” necessary to sentence someone to death. That was absolutely false: Under Supreme Court precedent, jurors must be given “clear and objective standards” and “specific and detailed guidance” about aggravating circumstances when weighing the penalty of death. A broad instruction like Owen’s could lead juries to consider irrelevant factors, leading to the unconstitutional “arbitrary and capricious” infliction of death. An appeals court set aside Jordan’s sentence.

In 1983, Jordan was granted a new sentencing trial. By this point Owen had moved to private practice—but at the behest of Marter’s family, he represented Mississippi as a special prosecutor. Owen secured yet another death sentence. But to do so, he persuaded the court to bar Jordan from introducing mitigating evidence—namely, testimony from several family members and a prison guard. The Supreme Court later held that convicts must be allowed to introduce such testimony, and Jordan’s death sentence was vacated.

At that point Owen entered into a plea agreement with Jordan. Under the agreement, Jordan would be sentenced to life without parole in exchange for his promise not to challenge his new sentence. A trial court accepted the plea and sentenced Jordan accordingly.

But the plea agreement Owen prepared turned out to be defective. Mississippi law allowed life without parole only for habitual offenders—which Jordan was not. Jordan asked the trial court to fix his unlawful sentence by changing it to life with the possibility of parole. The Mississippi Supreme Court agreed that Jordan’s previous sentence was invalid and sent the case back to the trial court. In the meantime, Mississippi had amended its laws to permit life without parole for all capital murder convictions.

Jordan asked Owen—who reprised his role as special prosecutor—to simply reinstate their previous life-without-parole agreement, which would now be valid. Owen refused. Instead, he sought a new sentencing trial—and asked the jury to sentence Jordan to death. The jury complied. After an extensive reprieve, Jordan found himself once again awaiting execution.

Repeatedly ensnared by the vagaries of Mississippi state law, Jordan had one final hope: the United States Constitution. Jordan argued in federal court that his new sentence violated the Due Process Clause, which prohibits prosecutorial vindictiveness. Owen, Jordan pointed out, had previously agreed to let Jordan live. But he later reneged on that agreement because—by his own admission—he was irked that Jordan had violated their original agreement. Yet Jordan only violated this agreement because it was illegal, something Owen should have realized before he crafted it. Jordan claimed that Owen’s refusal to negotiate another non-capital plea amounted to unconstitutional retaliation.

The district court rejected Jordan’s argument—and it refused to give him a “certificate of appealability,” or COA, which would permit him to appeal the court’s decision. He asked the 5th Circuit to consider granting him the COA so he could appeal his case. It refused—and, in the process, utterly botched the relevant case law. The 5th Circuit held that Jordan had “fail[ed] to prove” that Owen had acted out of vindictiveness, and thus could not appeal his case. But the Supreme Court has explicitly held that a prisoner need not prove his claim on the merits to obtain a COA. Instead, he need only show “something more than the absence of frivolity.”

By any measure, Jordan demonstrated that he had a serious—if not watertight—due process claim. Under established precedent, the 5th Circuit should have recognized that fact and given him a COA. Instead, it went ahead and evaluated the merits of Jordan’s case and ruled against him—in direct contradiction of the Supreme Court’s instruction. Jordan asked the justices to fix the error. On Monday, they refused.

In a subtly searing dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor—joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Elena Kagan—reprimanded her colleagues for refusing to address the 5th Circuit’s obvious mistake. She then noted six other cases in which the 5th Circuit refused to grant a COA by essentially ruling on the merits of the underlying claim. That’s unlawful, and the Supreme Court should have said so. Instead, the justices ignored the miscarriage of justice, allowing Jordan’s execution to move forward.

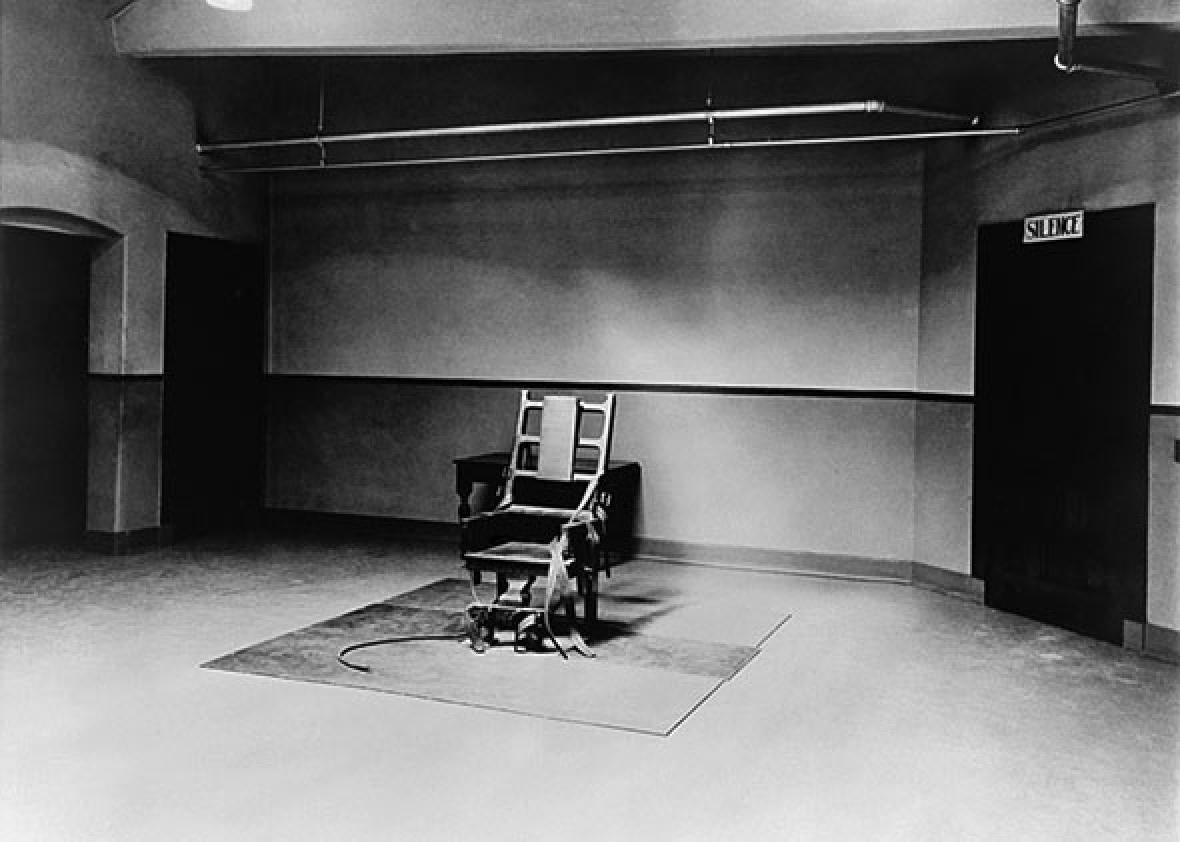

Mississippi’s attorney general will likely soon file a motion for an execution date. Soon after it is granted, Jordan will be put to death by lethal injection, ending his nearly four decades on death row. Owen may celebrate the long-awaited execution of the man he tried over and over again. But he should not pretend that his prosecution of Jordan came close to fulfilling the Constitution’s commands.