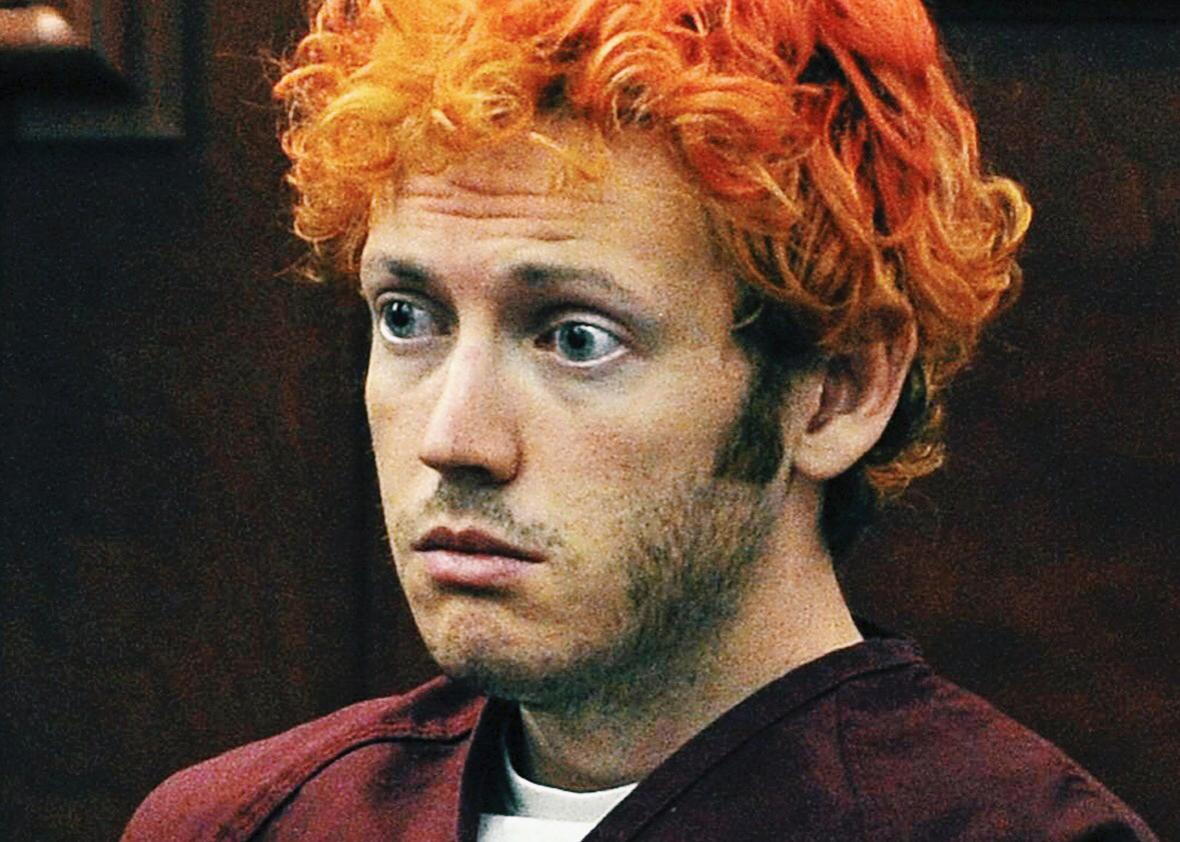

Late last week, after 12 weeks of testimony from more than 250 witnesses, and after a day and a half of deliberation, jurors in the trial of James Holmes found him guilty of murder for killing 12 people in an Aurora, Colorado, movie theater in July 2012. Holmes was deemed guilty on 24 counts of first-degree murder, 134 counts of first-degree attempted murder, six counts of attempted second-degree murder, and one count of explosives possession. This week, the sentencing phase begins, and Holmes faces the possibility of the death penalty for his crimes.

This will be the first death penalty sentencing hearing in Colorado in six years. It may go on for as long as a month. The same jurors who determined his guilt will now determine the sentence. The system in Colorado is designed to make imposition of the death penalty as difficult as possible. But the failed neuroscience graduate student, now 27, who became one of the nation’s worst mass shooters in a midnight killing spree, also faces a dedicated prosecutor and distraught victims who feel that if the ultimate punishment is appropriate for anyone, it’s Holmes.

As the Denver Post lays it out, this sentencing segment of the trial has three phases: The first is the aggravation stage, at which prosecutors must show that at least one aggravating factor makes this crime particularly heinous. There are 17 aggravating factors defined by statute in Colorado. Five are at issue in Holmes’ case, including the death of a child under 12 and killing multiple victims—both of which will likely be uncontested. The second phase is called the mitigation stage, at which the defense is expected to call Holmes’ parents and bring in evidence of his character, upbringing, and mental illness to show that despite the horrific nature of the crimes, life in prison is more appropriate than capital punishment. The jurors then have to weigh each mitigating factor against any aggravating factors. The third phase is the “victim impact” component at which the relatives of the murder victims will be asked to talk about how the killings affected their lives.

Finally, each juror must apply his or her reasoned, moral judgment to whether death is the appropriate penalty, beyond a reasonable doubt. At any stage in the sentencing hearing, the jurors can simply opt for life in prison. If they decide to impose capital punishment, they must wait until the end of the sentencing stage, and they must be unanimous. One juror holding out for a life sentence means no execution.

The issue at trial was not what Holmes did. This was never in dispute. He killed 12 moviegoers and wounded 70 others while they were trapped in a theater watching a midnight showing of The Dark Knight Rises, and he was arrested outside the theater with an AR-15 assault-style rifle, a Remington shotgun, and a Glock pistol. Had one of the weapons not jammed, there would have been many more deaths. The question was whether the attack was the product of months of deliberate planning, as asserted by the prosecutors, or a severe mental health problem, as asserted by his defense team.

As the prosecutor described it, Holmes’ careful actions on the night of the shootings, which included dressing in protective gear and booby-trapping his apartment, were the thinking of a calculating, evil, sane person. The lead prosecutor also emphasized that Holmes had what he called a “superior intellect.” Jurors were shown nearly 22 hours of videotaped interviews of Holmes speaking in a flat, mechanical tone about how he wanted to kill strangers to increase his self-worth. He explained that he felt nothing as he fired while, as the Boston Herald described it, “blasting techno music through his earphones to drown out his victims’ screams.”

Despite the fact that two court-appointed doctors who evaluated Holmes after the shooting found him legally sane at the time of the attack, the evidence of Holmes’ mental illness is pretty overwhelming. At trial, defense counsel argued that mental illness ran through both sides of Holmes’ family, that Holmes had attempted suicide at age 11, that he had “intrusive thoughts” in high school, and that by grad school, his “psychosis bloomed.” The defense team put into evidence a journal full of delusional rants Holmes had mailed to his therapist just before the shootings. (One excerpt: “Why? Why? Why? Why? Why? Life has no value whatsoever … Untruth is converted to truth by violence times zero, problem equals question mark, zero times problem equals question mark times zero, based on an incorrect theorem, zero equals zero, problem solved.”)

Holmes appears to have suffered a psychotic break in custody in prison, with footage that shows him banging his head on walls and babbling. He heard voices telling him not to eat red foods, and he smeared the walls with feces. He believed Barack Obama was talking to him through a television, ran head first into a wall, and licked the walls.

The defense’s star witness, Raquel Gur, head of the neuropsychiatry program at the University of Pennsylvania medical school, testified that extensive interviews with Holmes and assessment of his writings and brain scans indicated that he was severely delusional and legally insane at the time of the shootings. Holmes’ public defender argued that 20 different doctors who examined him in custody, plus the therapist who had been treating him before the shootings, said he was mentally ill, indeed all experts ultimately agreed he is on the schizophrenia spectrum. They simply disagreed over whether he was legally insane.

But the jurors determined that Holmes knew what he was doing the night of the shootings and that it was wrong. The legal standard for the insanity defense is notoriously high—the defense must show that mental illness prevented someone from understanding the wrongness of his criminal undertaking at the time of the offense. Because this common legal definition of insanity is so removed from the medical definition, only a small number of those who invoke the insanity defense succeed, and almost none of them prevail in high-profile cases like this one.

At trial, Judge Carlos Samour instructed jurors that Holmes could be determined legally sane if he had “a culpable state of mind” and acted with deliberation and intent—even if he had a mental illness.

This is an entirely different question from whether he should be executed for his crimes. Perhaps because the legal standard for insanity is so very difficult to meet—not just insane but also unaware of the difference between right and wrong—many trial watchers argued that the whole guilt phase was simply, as Frederick Leatherman put it, “a slow-motion guilty plea.” As he explained of capital defense lawyers, “when we lack a defense, instead of pleading guilty, we use the guilt phase to introduce evidence that mitigates the seriousness of the offense.”

What this means is that the evidence of Holmes’ schizophrenia probably couldn’t have helped him at the guilt phase, but it may yet become important to jurors at the sentencing stage. As Leatherman goes on to argue, “Holmes’s insanity defense [was] doomed because he admitted to police that he knew killing was wrong. But there is no dispute that he was mentally ill. While not a defense, mental illness is a powerful mitigating factor.”

We have written often here at Slate about the problem that while in 2002 the Supreme Court did away with capital punishment for anyone deemed “intellectually disabled”—generally with an IQ less than 75—having a mental illness, even a very severe mental illness, does not necessarily render you ineligible for the death penalty. While the high court technically forbids executing the “insane,” this prohibition is evaluated and implemented in all kinds of ways in the various states. The Death Penalty Information Center estimates that between 10 percent to 15 percent of people on death row in this country have some form of mental illness.

This is where it may matter that Colorado is not as enthusiastic about the death penalty as a state like, say, Texas, even in the face of one of the nation’s most horrific mass murders. Since 1977, only one person has been put to death in Colorado, and just three people currently sit on the state’s death row. One of those three received a “temporary reprieve” from Gov. John Hickenlooper, which began what seems like an unofficial moratorium in the state. But a new governor will hardly be bound by such a decision if and when Holmes’ case comes up for review, which may take up to 10 years. Colorado is also in the minority of states in that it places the burden of proof for an insanity plea on the prosecution instead of on the defense: Prosecutors had to show that Holmes was affirmatively sane at the time of the murders, which they were able to do at the guilt phase.

The majority of Holmes’ victims’ families have expressed a wish to see the death penalty imposed—even those who have personal moral qualms about capital punishment. The trial has been full of harrowing images and testimony that reveal just how profoundly the victims and the families of those killed or wounded in the attacks have suffered. Which means that the question for the jury, in the simplest form, is whether executing someone who is undisputedly mentally ill is something with which they are morally comfortable. This, then, will be the hard part, and it should be. Jurors at the guilt phase had to determine whether Holmes knew that killing those innocents was wrong. Now they need to decide whether killing a delusional schizophrenic is wrong.

The insanity defense is effectively a legal test unmoored from medical science. And the question of whether to execute the insane is a moral test almost completely unmoored from the law.