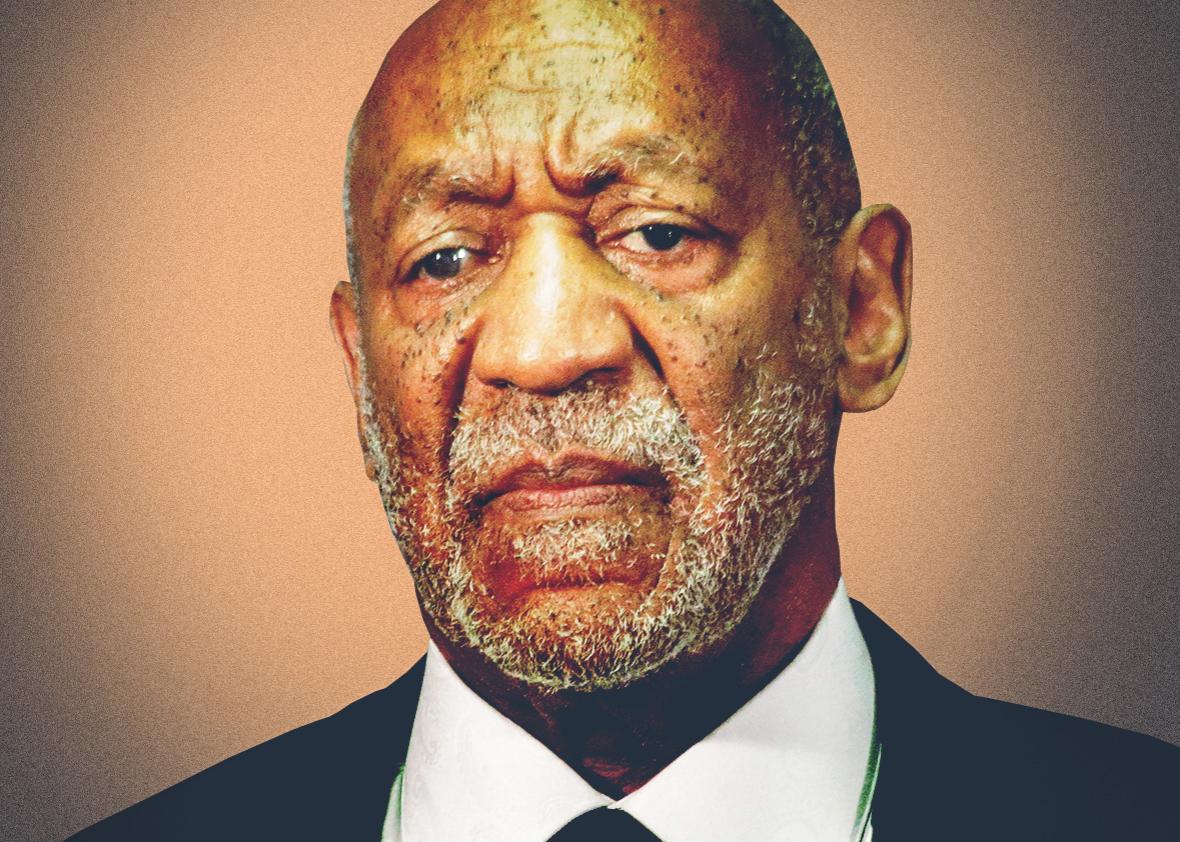

If Bill Cosby had resisted the urge to moralize, the 2005 deposition obtained this week by the Associated Press might have never come to light. In that document, Cosby acknowledged that in the 1970s he obtained Quaaludes, a now-illegal sedative, to give to women he wanted to have sex with. The deposition was sealed and remained so for a decade. But Monday the AP revealed that it convinced a judge to unseal a portion of the deposition—not because Cosby has been thrust into the news but because Cosby thrust himself into a public campaign of moralizing at black Americans.

Although the press and the public have a First Amendment right to access judicial proceedings in criminal cases, that right gets muddled in a civil complaint like this one. (Cosby’s accuser wasn’t trying to send him to jail; the statute of limitations had passed. She was suing him for damages.) Depositions are part of “discovery”—the phase of a lawsuit when each party makes the other produce relevant information. There’s no presumptive right for the press or public to access discovery materials, even when they’ve been filed with a trial court, as Cosby’s deposition had. Still, the American legal tradition frowns on absolute secrecy for any kind of court materials. So any party seeking to keep a deposition sealed must show “good cause” to keep the information out of the public eye.

In many cases, privacy interests constitute the good cause necessary to keep a deposition sealed. Private figures shouldn’t fear that intimate details of their lives will be revealed just because they’re involved in a lawsuit. And even public figures, like politicians and celebrities, maintain some privacy rights in civil suits. Cosby’s overall fame—his TV celebrity, his standup comedy—doesn’t automatically destroy his privacy rights as soon as he’s sued. As U.S. District Judge Eduardo Robreno explains in his order, that would create perverse incentives, encouraging gossip rags to file frivolous lawsuits just to get ahold of and publish information about celebrities’ private lives.

Instead, Robreno notes that a very specific aspect of Cosby’s public persona is at issue here: Cosby’s decision to don “the mantle of public moralist” and mount the “soap box to volunteer his views on, among other things, childrearing, family life, education, and crime.” As a mere comic, Cosby might maintain most of his privacy rights. But as a “public moralist,” he has “voluntarily narrowed the zone of privacy that he is entitled to claim.”

To prove his point, Robreno cites three of Cosby’s most infamous criticisms. First, Robreno describes the “pound cake” speech, delivered at an NAACP event celebrating the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education. During the speech, Cosby scolded black Americans for, among other things, allegedly stealing food:

Looking at the incarcerated, these are not political criminals. These are people going around stealing Coca Cola. People getting shot in the back of the head over a piece of pound cake! Then we all run out and are outraged, “The cops shouldn’t have shot him!” What the hell was he doing with the pound cake in his hand?

Robreno than cites a CNN interview with Don Lemon in which Cosby chastised black men for ostensibly abandoning their children and railed against the “no-groes” who defend black culture.

Finally, Robreno cites Cosby’s speech to Temple University graduates in which he told them that algebra is easier than cotton picking.

Because of harangues like these, Robreno writes, the AP has a legitimate interest in accessing Cosby’s deposition:

The stark contrast between Bill Cosby, the public moralist, and Bill Cosby, the subject of serious allegations concerning improper (and perhaps criminal) conduct, is a matter as to which the AP—and by extension the public—has a significant interest.

Weighing Cosby’s “diminished privacy interest” against the public’s interest in accessing his deposition, Robreno decided that the public’s interest should win out. Cosby failed to show “good cause” as to why his deposition should remain secret. As should usually happen in situations like these, transparency trumped secrecy.

A remarkably uninformed op-ed in the Federalist by Bill McMorris claimed that Robreno “unsealed Bill Cosby’s criminal record to punish him for saying things the judge doesn’t like.”* That is wrong as a matter of fact and a matter of law. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure lean toward judicial openness and thus require Cosby—not the AP—to show good cause for keeping his deposition sealed. Cosby failed to meet this standard, in large part because his moralization actually increased the public’s interest in the content of his deposition. McMorris and Cosby’s other defenders want to turn Robreno’s order into a political issue. It’s not. It’s an issue of law—and Cosby found himself on the wrong side of it.

Correction, July 8, 2015: This article originally misstated that an op-ed by Bill McMorris ran in the Washington Free Beacon. It ran in the Federalist. (Return.)