Neal Horsley died last month at the age of 70. You may not recognize his name, but chances are you’ve heard of how he terrorized abortion providers and made them fear for their lives. His tactics, still in effect today, continue to threaten abortion providers across the country.

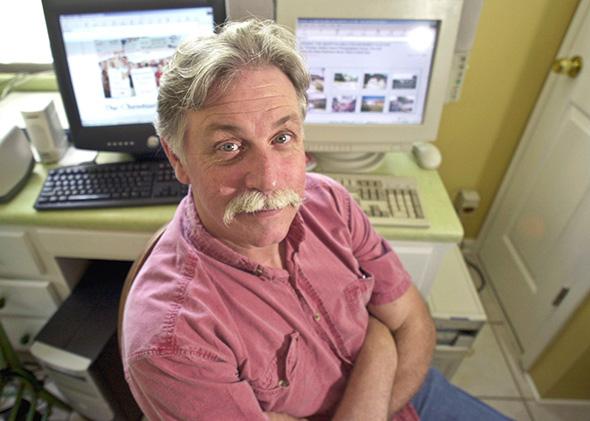

Horsley was the anti-abortion extremist responsible for assembling the infamous “Nuremberg Files” website. The website was ultimately the subject of a lengthy legal battle testing the line between free speech and a true threat, a legal boundary the Supreme Court is currently reconsidering.

Horsley’s website, created in 1997, listed roughly 200, as the website called them, “abortionists.” These abortion providers were listed in three different fonts, as described by the site’s legend: “Black font (working); Greyed-out Name (wounded); Strikethrough (fatality).” In addition to this list, the website included the abortion providers’ personal information, such as their home addresses, phone numbers, and photographs.

The website, donned with blood-dripping graphics, both celebrated providers’ deaths and, with a wink and a nod, encouraged others to harm the remaining providers on the list so that more names could be crossed off.

An Oregon Planned Parenthood affiliate and several individual abortion providers brought a lawsuit against the website under the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act. This law, enacted in 1994, prohibits, among other things, the use of “force or threat of force” to intentionally intimidate any person seeking to obtain or provide reproductive health services. Planned Parenthood argued that such a “threat” existed based on Horsley’s website as well as two posters from an anti-abortion group associated with Horsley. One poster, displayed at anti-abortion events and reprinted in anti-abortion publications, displayed the images and identifying information of 13 abortion providers and labeled them as the “Deadly Dozen” who were wanted as “GUILTY.” Another “wanted” poster, displayed publicly outside of a courthouse, targeted a specific abortion provider and likewise labeled him “GUILTY.”

After a lengthy legal battle, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit agreed with Planned Parenthood, ultimately finding that, in conjunction with being named in the posters, the providers’ listing on the Nuremberg Files website constituted a true threat. The court concluded in 2002 that “being listed on a Nuremberg Files scorecard for abortion providers impliedly threatened physicians with being next on a hit list.” As a result of the case, Horsley removed the Nuremberg Files website.

However, the site lives on, both in Internet remnants hosted by anti-abortion extremists as well as in tactics that anti-abortion extremists continue to use to harass and terrorize abortion providers to this day. Based on research that we’ve conducted over the past four years that forms the basis of our new book, Living in the Crosshairs: The Untold Stories of Anti-Abortion Terrorism, one of the most common forms of harassment that abortion providers live with on a daily basis is the distribution of personal information online.

Many abortion providers throughout country have experienced this type of harassment: Abortion opponents take photos or videos of providers and post them online; anti-abortion extremists post personal and identifying information about providers, such as their names, addresses, and phone numbers; opponents dig up and publicize information such as providers’ educational backgrounds, the names and occupations of family members, the schools their children attend, even the names of charities to which providers donate money.

In finding and publicizing this personal information, the message is clear, and it’s the same one Horsley conveyed through the Nuremberg Files. As one abortion provider, whose personal information was recently put on the Internet and whose house was picketed, told us: “They think that if people are identified, if videos are put on YouTube, if they have our license plate and home address, it’s just a way of bullying and harassing people.” Another provider explained the intimidation involved: “The protesters make the assumption that abortion providers are intimidated when personal information is in the hands of antis. It is never with the intent of ‘I know you’re an abortion provider,’ but more specifically, ‘I know who you are and you should be concerned that I know who you are.’ ”

Even more concerning, as one provider told us, the use of this personal information is “terrifying because what they’re doing is trying to provoke nutty people to take action.” Or, put differently by another provider, it “facilitates the crazies doing their thing.”

This fear is justified. Since 1993, eight abortion providers have been murdered because of their jobs (and a possible ninth, though there is a dispute over whether the murder was abortion-related). The most recent assassination was of Dr. George Tiller in 2009, shot while he was serving as an usher in his church. Several of the murders were preceded by Old West–style “wanted” posters that featured providers’ personal information, a tactic still in use today.

Just as Horsley capitalized on past murders with his website, the current anti-abortion extremists who employ the same tactics are capitalizing on them as well. They are threatening abortion providers in a way that raises the same concerns that came before the 9th Circuit when it ruled that the Nuremberg Files website was part of a threat not protected by the First Amendment.

This issue of what constitutes a “threat” and is thus not constitutionally protected free speech is currently before the Supreme Court. In Elonis v. United States, which was argued in December and will be decided by the end of June, the court is considering a case in which a man posted alleged threats to Facebook. The relevant legal issue is the extent to which courts should determine whether a statement is a “threat” based on the speaker’s own subjective intent or based on whether a reasonable person would find the statement threatening.

The outcome could have big implications for abortion providers who live with the ongoing legacy of Horsley’s online threats. It is imperative that, beyond merely the speaker’s subjective intent, context also be considered a critical aspect of the inquiry into what constitutes a “true threat.” Providers go to work every day with the collective memory that people who worked in their same job have been terrorized, violently attacked, and murdered. In this profession, a statement that is otherwise not threatening to a layperson unaffiliated with abortion care may in fact be terribly threatening to an abortion provider, and the legal standard should reflect that.

As threatening as these tactics are, though, only a small number of abortion providers leave the field as a result. Instead of giving in, they remain committed to their patients, to women’s rights, and to public health. In continuing despite the threats, they have ensured that Neal Horsley died without accomplishing his goal of ending abortion in the United States.