“I think we need to kill more people,” Dale Cox, a prosecutor in Caddo Parish, Louisiana, said recently. He was responding to questions about the release of Glenn Ford, a man with Stage 4 lung cancer who spent nearly three decades on death row for a crime he did not commit. Cox acknowledged that the execution of an innocent person would be a “horrible injustice.” Still, he maintained of the death penalty: “We need it more now than ever.”

Cox means what he says. He has personally secured half of the death sentences in Louisiana since 2010. Cox recently secured a death sentence against a father convicted of killing his infant son, despite the medical examiner’s uncertainty that the death was a homicide. Rather than exercising caution in the face of doubt, Cox told the jury that, when it comes to a person who harms a child, Jesus demands his disciples kill the abuser by placing a millstone around his neck and throwing him into the sea.

The nation suffered more than 10,000 homicides last year, yet only 72 people received death sentences—the lowest number in the modern era of capital punishment. The numbers have been steadily declining for the better part of a decade. Most states are abandoning the practice in droves. Even in states that continue its use, capital prosecutions are being pursued in only a few isolated counties.

What distinguishes these counties from neighbors that have mostly abolished the death penalty, in fact if not in law? Perhaps the biggest factor is the presence of a handful of disproportionately deadly prosecutors who represent the last, desperate gasps of a deeply flawed punishment regime. Most of their colleagues are wisely turning away from a practice that has revealed itself to be ineffective at deterring crime, obscenely expensive, inequitably administered, and not infrequently imposed upon the innocent. But America’s deadliest prosecutors continue to pursue death sentences with abandon, mitigating circumstances and flaws in the system be damned.

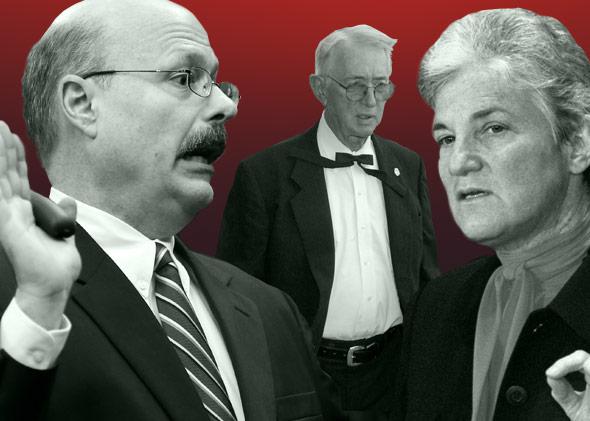

Cox is one of them. Jeannette Gallagher of Maricopa County, Arizona, is another. She and two colleagues are responsible for more than one-third of the capital cases—20 of 59—that the Arizona Supreme Court reviewed statewide between 2007 and 2013. Gallagher recently sent a 19-year-old with depression to death row even though he had tried to commit suicide the day before the murder, sought treatment, and was turned away. She also obtained a death sentence against a 21-year-old man with a low IQ who was sexually abused as a child, addicted to drugs and alcohol from a young age, and suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. She then sent a U.S. military veteran with paranoid schizophrenia to death row. Her response to these harrowing mitigating circumstances has not been to exercise restraint, but rather to accuse each of these defendants of simply faking his symptoms. The Arizona Supreme Court has found misconduct in three of her cases, labeling her behavior as “inappropriate,” “very troubling,” and “entirely unprofessional.”

Gallagher’s colleague in the district attorney’s office, Juan Martinez, has a comparable record. He once likened a Jewish defense lawyer to “Adolf Hitler” and his “Big Lie,” a tactic the Arizona Supreme Court deemed “reprehensible.” One judge noted of Martinez: “You’re at war, almost nuclear war, the minute you come up against him.” The recent trial of Jodi Arias, a woman who claimed that she killed her boyfriend in self-defense, was a rare case in which Martinez failed to secure a death sentence. When defense counsel Jennifer Willmott asserted that the victim had been suicidal, he responded: “If Ms. Willmott and I were married, I certainly would say, I fucking want to kill myself.” The Arizona Supreme Court has found his behavior, like Gallagher’s, to constitute prosecutorial misconduct.

Meanwhile, in Duval County, Florida, Bernie de la Rionda has personally obtained 10 death sentences since 2008. (He failed to secure the conviction of George Zimmerman, however, for chasing down and shooting teenager Trayvon Martin.) The Florida Supreme Court reversed three of those cases; one for law enforcement misconduct and two after concluding that death was too severe a punishment. That court also reversed an earlier death sentence because de la Rionda repeatedly harped about the defendant’s sexual preferences and views on homosexuality, despite the trial court’s warning that the evidence was irrelevant.

Excessive charging in Duval County reaches all the way up to elected State Attorney Angela Corey. About one-quarter of Florida’s death sentences come from Duval County even though it holds only 5 percent of the state’s population. Stephen Harper, a law professor and former defense attorney, told the Florida Times-Union that Duval County has more death sentences than the much more populous Miami-Dade County due to “the simple fact … that Angela Corey prosecutes cases that [Miami-Dade State Attorney] Katherine Rundle wouldn’t touch.” “Rundle’s prosecutors were reluctant to put anyone on death row who had been repeatedly abused as a child,” the Times-Union reported. “Corey hasn’t shown the same restraint.”

Corey drew national attention when she transferred Cristian Fernandez, then a 12-year-old boy, from the juvenile system to adult court, where he faced up to a life sentence for the murder of his 2-year-old half brother.* She did so despite his young age and the persistent sexual and physical abuse that Cristian endured as a child. Corey is also the prosecutor who sent Marissa Alexander, a woman with no criminal record, to jail for 20 years after she fired a warning shot at her horribly abusive husband that hit neither him nor anyone else.

Not surprisingly, death sentences drop precipitously after these prosecutors leave office. Bob Macy sent 54 people to Oklahoma’s death row before retiring in 2001. Over the past five years, Oklahoma County has had only one death sentence. Lynne Abraham secured 45 death sentences as the Philadelphia district attorney. Since she retired in 2010, the new district attorney has obtained only three death sentences. Joe Freeman Britt, dubbed the deadliest prosecutor in America, secured 42 death sentences during his tenure in Robeson County, North Carolina. Last year DNA evidence led North Carolina officials to release two intellectually disabled half brothers, Henry Lee McCollum and Leon Brown, each of whom served 30 years—with McCollum under a sentence of death—for a rape and murder they did not commit. Britt is the prosecutor who sent McCollum, a man with the mental age of a 9-year-old, to death row. Britt retired in the 1990s, and the county has imposed only two death sentences in the past decade.

These drops underscore the degree to which prosecutors such as Dale Cox, Jeannette Gallagher, Juan Martinez, and Bernie de la Rionda are out of step with the times. Twenty years ago, when support for capital punishment was at an all-time high, these prosecutors often touted their death sentences proudly, like medals of honor to display to a receptive public. Today the electorate is in a decidedly different mood. The curtain has been pulled back not just on our nation’s deeply flawed application of the death penalty, but on broad swaths of the justice system. These prosecutors increasingly look irresponsible and reckless, wasteful of precious public resources, and decidedly lacking the humility or judgment required of public officials entrusted with life-and-death decisions. We can only hope that, unwittingly, their inability to temper their own bloodthirsty impulses will further illuminate the ugly truth about capital punishment, and hasten its demise once and for all.

*Correction, May 15, 2015: This article originally misstated that Cristian Fernandez was 13 years old when Florida State Attorney Angela Corey transferred him from the juvenile system to adult court. He was 12 years old. (Return.)