There’s wide consensus around the video: Walter Scott was shot and killed in cold blood as he ran for his life from Michael Slager, the cop who stands charged with his murder in North Charleston, South Carolina. But Scott’s demise was set in motion moments earlier, when Slager decided to pull him over for a traffic violation—a stop that never should have happened.

The dashcam video leaves no doubt as to why Slager pulled over Scott: “The reason for the stop is that your third brake light’s out,” Slager told Scott, minutes prior to the fatal shooting.

Slager’s asserted “reason” had no premise in South Carolina law: Scott’s vehicle was in full compliance. Lacking reasonable suspicion that Scott was doing something illegal, Slager should’ve never pulled him over in the first place, unless his true motive was something other than a concern for enforcing the laws he took an oath to uphold.

Policing minor traffic violations as a pretext for more intrusive, “crime-fighting” stops is a real and dangerous problem—Slate’s Jamelle Bouie broke down the numbers of how people of color are hit hardest by this rampant style of roadside discrimination.

But there’s another problem: The legal pretexts police use for such traffic stops can be plainly mistaken or made up.

South Carolina law is straightforward on the issue of third brake lights. Motor vehicles must be equipped with “a stop lamp on the rear”—a singular brake light, which is to be maintained in good working order. A South Carolina appeals court confirmed this reading: A single operating brake light means a vehicle is “in full compliance with all statutory requirements regarding rear vehicle lights,” and a stop premised on requiring anything more is “unreasonable” and thus a violation of the driver’s constitutional rights. However, the decision was later overturned on appeal.*

So why did Slager pull over Scott? If what he said, as captured on the dashcam account, is to be believed, Slager made a mistake and decided to “seize” Scott for a law not in the books. In a perfect world, such errors should never give a police officer an opportunity to stop anyone.

That perfect world was shattered in December, when the Supreme Court blessed the shady police practice of pulling someone over for breaking a law that doesn’t exist. The case was Heien v. North Carolina, involving the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches and seizures—the only shield against police overreach during close encounters with law enforcement. In an 8-to-1 decision, the court ruled that “reasonable” mistakes about what the law is can justify police stopping an otherwise law-abiding citizen.

Chief Justice John Roberts, who doesn’t seem to get pulled over often, announced the Heien reasoning with elegance: “To be reasonable is not to be perfect, and so the Fourth Amendment allows for some mistakes on the part of government officials, giving them fair leeway for enforcing the law in the community’s protection.”

It’s hard to argue with any of that, except for the fact that nowhere in the pronouncement is there any mention that the Fourth Amendment exists to protect the community from the government. Roberts’ formulation makes it seem as if the provision exists to protect the community from criminals.

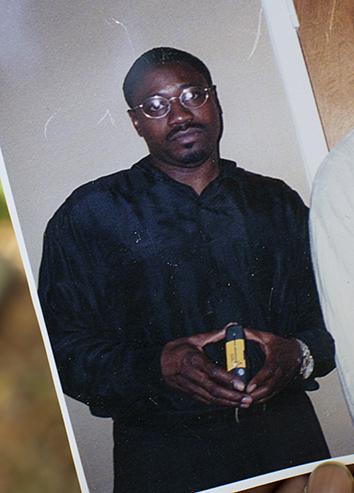

Photo by Randall Hill/Reuters

And maybe Nicholas Heien, the petitioner in that case, was a criminal. When a North Carolina police officer pulled over Heien and Maynor Javier Vasquez in 2009, the officer informed them that they had been stopped “for a nonfunctioning brake light”—the same line Slager used on Scott. Heien, the owner of the car, got a warning citation and everything should’ve ended there. But the officer, for some unexplained reason, decided to ask Heien if he could give the car a “quick check” to ensure there were no “drugs or guns or anything like that.” That’s when Heien—against his better judgment—consented to the search, which revealed a baggie of cocaine, and everything went downhill for the two men.

Perhaps Heien and Vasquez got what they deserved, but should the car have been pulled over in the first place? Like South Carolina’s, North Carolina law only requires one working “stop lamp” in vehicles. (In the vast majority of states, the norm is two such lamps.) So if Heien’s single working brake light meant he was in compliance with the law, what legal justification did the officer have to perform the traffic stop to begin with? Shouldn’t the law enforcer know the essence of the traffic laws he’s enforcing, especially for something so common and straightforward as properly working taillights?

Not exactly, said the Supreme Court. Roberts and seven other colleagues were largely unpersuaded by the argument that if ignorance of the law is no excuse for the average citizen, it shouldn’t be an excuse for police officers, either. To the court, cops are just different. They get a pass for being ignorant about the law, so long as the ignorance is “reasonable.”

The lone dissenter, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, seemed to grasp the consequences of the court’s lopsided logic. Acknowledging that traffic stops “can be annoying, frightening, and perhaps humiliating,” Sotomayor argued that “an officer’s mistake of law, no matter how reasonable, cannot support the individualized suspicion necessary to justify a seizure under the Fourth Amendment.” More strikingly, she seemed to speak to our recent conversations around policing, portending that the Heien decision would lead to an erosion “of civil liberties in a context where that protection has already been worn down.”

The video of Scott running for his life as a result of a mundane traffic stop makes it clear that Sotomayor was right. Her focus on the experience of being confronted by the police, especially for communities where constitutional protections are thinner than anywhere else, was the more realistic approach. Other systemic factors surely played a role in Scott’s death—starting with the fact that too many police officers find it odd for someone to drive a luxury car while black. But it all began with that initial traffic stop, an unjustified intrusion on Scott’s freedom premised on Slager’s apparent ignorance of South Carolina law. Ignorance, the Supreme Court has now ruled, is an excuse for cops to get away with things you and I can’t.

Update, April 15, 2015: This story originally stated that a South Carolina appeals court ruled that it is unreasonable for police to stop a vehicle based on a missing light. That ruling was overturned on appeal. (Return.)