DNA testing has been used 329 times now to prove the innocence of people wrongly convicted of a crime. But what happens when there is no DNA evidence to prove someone’s innocence? What happens when there is only his word, and the mounded doubts of the team that prosecuted and convicted him? And what happens when—despite growing certainty that it has imprisoned the wrong man for more than 20 years—the Commonwealth of Virginia stands poised to keep him locked up, possibly forever?

Of all the maddening stories of wrongful convictions, Michael McAlister’s may be one of the worst. For starters, he has been in prison for 29 years for an attempted rape he almost certainly did not commit. For much of that time, the lead prosecutor who secured his conviction, the original lead detective on the case, and more recently, the current Richmond Commonwealth’s Attorney, Michael Herring, have argued that McAlister is innocent and that someone else—a notorious serial rapist with the same MO as the perpetrator of the crime for which McAlister was convicted—is in fact the real criminal. “I think our justice system is one of the best on the planet,” Herring told the Richmond Times-Dispatch last week. “But this case makes me ashamed of it.”

Beyond the injustice of his wrongful conviction, McAlister, now 58, faces yet another legal nightmare: His release date of Jan. 15, 2015, has come and gone, and he is still locked up. He faces the possibility of almost indefinite commitment because Virginia plans to hold him as a sexually violent predator based largely on his 1986 conviction, a conviction that prosecutors long ago began to doubt. The indispensible Frank Green of the Richmond Times-Dispatch, who has been reporting on this case since 2002, has the whole story here. The short version is that McAlister may well continue to be imprisoned indefinitely by a justice system that operates along your basic “Hotel California” principles: You can check out anytime you like, but you can never leave.

In a last-ditch effort to end this march of the surreal, McAlister’s lawyers and Herring filed a petition Wednesday to Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe for an absolute pardon. Absent that, the system will grind onward and an innocent man may be incarcerated for years for a crime nobody truly believes he committed.

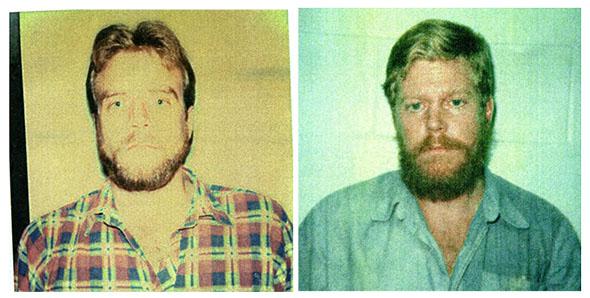

Here are the facts: In 1986, McAlister was convicted of attempted rape and abduction with the attempt to defile, after a 4½-hour bench trial. The only evidence presented was the victim’s identification based on her partial glimpse of her assailant’s face, much of which was covered with a mask. The photo array she was shown by the police did not include a picture of Norman Derr, a serial rapist who had already attempted to attack another woman in the same apartment complex. But it did include a photo of McAlister, and the two men looked astonishingly similar.

Derr is currently serving three life sentences. He was caught after the brutal rape of a woman in 1988 and is now linked to six other violent offenses through DNA cold-case testing. (There was no biological evidence from the crime McAlister was convicted of, and thus nothing to implicate Derr and exonerate McAlister.) But the similarities between Derr’s crimes and the alleged McAlister assault are remarkable: Derr attacked women with a knife in apartment-complex laundry rooms, wearing a plaid shirt and a stocking mask. These details all match the crime for which McAlister is still in prison. Subsequent police affidavits reveal that Derr was already being trailed by the police in 1986 and that he had in fact pulled on a stocking mask and approached a female undercover cop in the same apartment complex in which McAlister allegedly later assaulted his victim. Several other laundry room attacks happened after McAlister was already in jail but before Derr was caught.

In the petition asking McAuliffe to release McAlister, his lawyers write that the officers who convicted him are now certain Derr was in fact to blame and that they “believe it is highly improbable that another stocking-mask-wearing, knife-wielding, 6-foot-tall white man with shoulder-length blond hair was terrorizing women at night in the Town & Country apartment complex laundry rooms during that same period in time.”

Bureaucracy and haste were responsible for the fact that in the moment the cops failed to draw the obvious conclusions. Instead, they focused their investigation on McAlister, who had been involved in several incidents of alcohol-related public indecency. A detective investigating the rape asked McAlister to wear a plaid shirt, took his photograph, and then included it in a photo lineup shown to the victim. The attacker had worn a plaid shirt. McAlister was the only one in the photo array wearing one. Derr was not in the original photo array at all.

The original assistant commonwealth’s attorney assigned to the case, Mark Krueger, was reluctant to prosecute from the very outset because the victim was unable to give a definitive description of the suspect. He admitted to one Richmond police officer that he was feeling “he may have the wrong suspect.”

Based only upon the identification testimony, McAlister was sentenced to 35 years in prison. After he was convicted, evidence continued to pile up that Derr had committed the crime. In 1993, both the prosecutor and the investigator appeared at a parole hearing for McAlister, testifying that they both believed the wrong man had been convicted. McAlister was not paroled or pardoned then, and he served out most of his sentence. In 2002 the Richmond Times-Dispatch’s Green began writing about the case, quoting the prosecuting commonwealth’s attorney, Joe Morrissey, saying “it’s the one case out of thousands that has always troubled me. I’m literally shocked that he’s still locked up.” McAlister’s 2002 petition to then-Gov. Mark Warner was denied in 2003 because there was no DNA evidence to exonerate him.

McAlister was finally paroled in 2004. He fell into a depression, started drinking, and violated parole by driving under the influence. He was sent back to prison the following year and has been there ever since. His release date should have been in January of this year.

Here is where we are stuck. Virginia passed a statute in 1999 requiring civil commitment for “sexually violent predators,” a designation that includes McAlister because of his initial, almost certainly wrongful conviction. As the time neared for his release, rather than being freed, he was shuttled into a system that will determine whether he is too sexually dangerous for release. He faces a probable cause hearing on May 18 at which a judge will decide whether he is a sexually violent predator and whether to initiate proceedings that could result in his indefinite detention at a secure state rehabilitation facility.

At this upcoming civil commitment hearing, McAlister is not allowed to challenge the validity of his prior convictions, and he cannot ask the judge to consider his actual innocence. Moreover, if McAlister declines to admit to the offense for which he served time, it will likely count against him. (It gets worse: McAlister admits to having a sexual disorder—exhibitionism—but he was not able to get sex offender treatment while in prison without first admitting to his guilt with respect to the attempted rape.) To summarize, he was jailed for a sexually violent act he maintains he didn’t commit, and in order to avoid prolonged civil commitment for that act, he needs to admit that he did it. A Catch-22 without the laugh line.

Herring, the current Richmond Commonwealth’s attorney, told the Richmond Times-Dispatch that, “McAlister’s case presents the nightmare scenario we all fear—overwhelming evidence of systemic failure at just about every juncture.” He added that although the prosecution team had contemporaneous doubts about his guilt, “the concerns were ignored. Roughly 29 years later, the commonwealth is poised to double down on its mistake by seeking to have him declared and held as a sexually violent predator for a crime he didn’t commit.”

Seeking an absolute pardon is a serious remedy. But unless he is pardoned for the underlying crime that will trigger civil commitment, McAlister is trapped in a world that makes no legal sense: Nobody believes he did the crime, but he will never, ever stop doing the time. As the petition filed with McAuliffe notes: “The power of the pardon is a weighty responsibility and is not to be exercised lightly. But there is unlikely to be another non DNA-based pardon petition in which the evidence of innocence is as strong as it is here.”

Shawn Armbrust, executive director of the Mid-Atlantic Innocence Project, which involved itself in McAlister’s case last year, choosing it from among thousands, explained in a phone interview that allowing this to play out in the civil courts may take years and years and that really the only recourse that could free McAlister immediately is action by the governor: “The only person who can end this nightmare is Gov. McAuliffe, and if he doesn’t do it, there’s no telling when it ends. It’s already gone on for 29 years too long.”