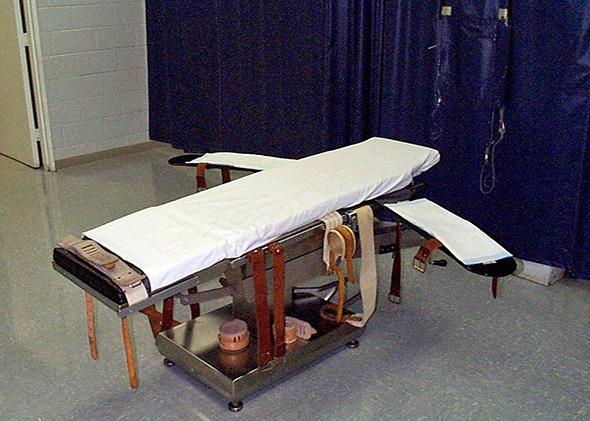

A series of botched executions in Ohio, Oklahoma, and Arizona last year raised serious new questions about how death penalty drugs are administered. They have drawn fresh scrutiny from the Supreme Court itself, which agreed last month to assess whether a lethal injection cocktail used in Oklahoma violates the Eighth Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishment. A month ago Ohio announced that officials would stop using one of the drugs in the current protocol, midazolam, after a botched execution involving untested drugs last year. And on Friday, Ohio Gov. John Kasich announced that the state would postpone all seven scheduled 2015 executions, partly because of questions surrounding the controversial drug cocktail Ohio had been using.

Yet just prior to announcing this temporary moratorium, Ohio lawmakers attempted to improve the reputation of its capital punishment system with bizarre new laws passed in a lame-duck session. The controversial rules increased secrecy by shielding the identities of drugmakers and suppliers for lethal injections, and they immunized error by providing anonymity for anyone who participates in the process as well as the state execution team. The effect, as the Washington Post editorialized, was “to impose a gag order on potentially adverse reports that could inform the public debate over capital punishment.”

But while Ohio officials eventually came to realize that the problems with their lethal injection protocol couldn’t be wholly fixed by shrouding executions in ever more secrecy, Virginia lawmakers have arrived at the opposite conclusion. Last week they proposed legislation that would make it easier to obtain lethal injection drugs and that would also create an almost impermeable layer of secrecy around the execution process. The new law would make it significantly harder for the press and the public to know what was happening in the execution chamber. This is, of course, the same Virginia Legislature that flirted last year with reinstating the electric chair if lethal injection drug supplies dried up. (That effort failed.) The effect of this new proposed legislation would be less scrutiny of a process that the rest of the nation, including the highest court in the land, views with ever more skepticism.

Amid the recent rash of high-profile screw-ups in executions, new cover-up measures have been passed in more than a dozen states, allowing departments of corrections to increasingly refuse to disclose where their execution drugs come from, how and if they were tested, and whether corrections officers are qualified to administer them correctly. In response to these clampdowns on information about how tax dollars are being spent and how prisoners are being executed in their citizens’ name, lawsuits have been filed by capital defense attorneys, civil liberties groups, and news organizations in Oklahoma, Ohio, Missouri, Georgia, Tennessee, Pennsylvania, and Arizona.

This increased scrutiny into the machinery of death bears out reasons for public concern. As the Daily Beast recently noted, court pleadings in an Oklahoma suit reveal that Mike Oakley, the former general counsel for that state’s Department of Corrections, has said that his research on the drug midazolam included “WikiLeaks or whatever it is.” Justice Sonia Sotomayor, dissenting from the court’s decision to allow Oklahoma to execute yet another capital defendant, noted in January that the state’s expert witness defended the use of midazolam but “cited no studies” and “instead appeared to rely primarily on the web site www.drugs.com.”

Still, in the jubilant spirit of “if you can’t fix it, hide it,” Virginia is considering the proposed legislation, sponsored by Senate Minority Leader Richard L. Saslaw, D-Fairfax, and called Senate Bill 1393. At one level, by loosening the rules on pharmacies that compound drugs, it will make it easier for the commonwealth to obtain the lethal-injection drugs that have been ever-more difficult to procure after U.S. suppliers stopped making them and European companies refused to allow them to be used in executions. But the bill goes far beyond that, by protecting from public view “all information relating to the execution process” and elsewhere ensuring that “information relating to the identity of … compounding drugs for use in executions and all documents related to the execution process are confidential, exempt from the Freedom of Information Act, and not subject to discovery or introduction as evidence in a civil proceeding except for good cause shown.”

What makes the bill extraordinary isn’t just the exceptionally broad language that hides from public scrutiny “all information relating to the execution process” but also the notion that it cannot be used in any civil litigation. Amazingly, the Democratic administration of Gov. Terry McAuliffe supports the new secrecy measure, citing “security” concerns. While members of the subcommittee that debated the legislation last week claimed they would amend it to require that the state disclose what drug or drug combination were being used to kill people, the broad secrecy language hiding “all information” is pretty clear on its face. At the hearing last week, Saslaw argued that the object of the proposed bill was to protect the safety of those who administer capital punishment, saying: “There ain’t a state in America that gives you the name of the guy who sticks the needle in any more than you got the names of the folks who pulled the switch when we had the electric chair.”

Corinna Barrett Lain, a professor at the University of Richmond School of Law, argued against the secrecy language at last week’s hearing. She says the proposed measure is “the most broad secrecy statute in the country because it says ‘all information about the execution process,’ which by its plain text would include even a botched execution itself.” In an email she notes that Saslaw’s analysis about the guy who pulls the switch on the electric chair should not extend to the drugs used in an execution: “The identity of the executioner is not a constitutional matter. The contents of the syringe are,” she writes.

In her testimony Lain pointed out how absurd it is to hide government actions and accountability precisely when the state must be held to account: “It strikes me as the essence of bad government to enshroud the government in secrecy in its most powerful moment—when it exercises its sovereign right to take the life of one of its citizens.” She added that this bill ensures that “there are no questions asked about where the drugs came from, what the drugs are, what their potency is, whether they have been contaminated, whether they are expired, indeed whether they were obtained legally.”

I have long been curious about the argument that marauding death penalty opponents race around America, roughing up the pharmacists and corrections officials who participate in their state capital punishment apparatus, thus warranting increased secrecy. So I checked with Frank Knaack, the director of public policy and communications with the ACLU of Virginia. He says he knows of no such incidents, noting that the commonwealth’s Department of Corrections has made all of its information available on the drugs used and the procedures followed for 10 years and “there is no evidence of a problem, or reason to believe that Virginia taxpayers can’t be trusted with this information.”

Knaack also points out that Virginia, where there are eight people on death row and where there is still a supply of lethal injection drugs, assumes another problem that simply doesn’t exist: that there will be a massive shortage of lethal injection drugs and a huge increase in capital defendants. The fact that the commonwealth executes relatively few people, combined with the lack of evidence that we must hide the identity of everyone involved in an execution, certainly suggests that the new law isn’t so much protecting the machinery of capital punishment as it is drawing a curtain around the death chamber for the sake of secrecy itself. That all information surrounding an execution is exempted not just from FOIA scrutiny, but also largely from use in civil suits, sounds like it has more to do with a panicky cover-up than with prison security.

There could be an unintended benefit to the legislation for opponents of capital punishment. Lain, a former prosecutor, notes that the paradox of the current solution to a nonexistent problem guarantees that those eight death penalty cases will be tied up for years, as lawyers battle it out with the state over matters of transparency: “This bill ensures that executions will be hung up in litigation for as long as lawyers can drag it out. And while the U.S. Supreme Court doesn’t seem to care much about the death penalty, it does care about process, and it’s the cover-up that’s going to get these states into trouble.”

Say what you want about the death penalty, but few Americans—and presumably even fewer jurists—affirmatively want to see it administered sloppily, violently, by way of untested combinations of drugs procured from ambiguous sources. As nationwide support for the death penalty continues to drop, those who believe in capital punishment will need to come up with better arguments than “nothing to see here, folks.” Any good mobster can tell you that it’s not the crime that will get you in the end; it’s the cover-up. And the states that are trying mightily to cover up what happens in their death chambers are mostly just doing a good job of signaling that whatever they are doing in there bears closer watching.