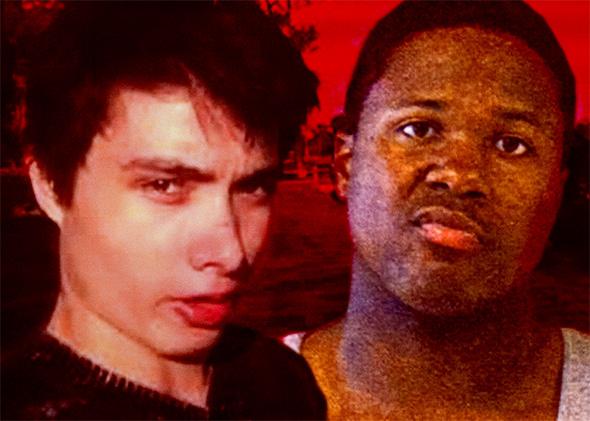

On Saturday, Ismaaiyl Brinsley shot his ex-girlfriend Shaneka Thompson in the stomach. If that were all he did, most of us would never have heard of him today.

We live in a country where shooting your ex-girlfriend is at most local news. According to media reports, the management of Thompson’s apartment complex distributed a letter to other residents stating that her shooting was the result of a “domestic dispute” in order to reassure them that “this was a private, isolated incident.” When three women are murdered by their husbands or boyfriends every single day in the United States, domestic violence is just another routine event—merely a landlord-tenant-relations issue of no concern to anyone else.

Of course, later that day Brinsley went on to murder New York police officers Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos, so we now know that his shooting of Thompson was no private, isolated incident. The more difficult question is why anyone ever assumed that it was.

Too often, our society resists taking domestic violence and other forms of gendered violence, such as stalking and sexual assault, as seriously as other kinds of violence. We need to stop dismissing gendered violence and start learning from the pattern present in one incident after another. Men who engage in violence at home are often men who engage in violence outside the home. And men who devalue women’s lives are, by definition, men who devalue human lives.

Brinsley is far from the first to lay bare the connection between gendered violence and other violent acts. Before Cho Seung-Hui killed more than 30 people in the horrific Virginia Tech massacre in 2007, police investigated him for two separate reports of stalking by female classmates.

This year, not long before Elliot Rodger launched a shooting spree in Isla Vista, California, that left six dead and 13 wounded, he authored angry and misogynistic tirades in various online forums, threw coffee on “two hot blonde girls” at a bus stop after they failed to smile at him, and tried to push women over a ledge at a party.

And just a few days ago, Man Haron Monis held 17 people hostage for more than 12 hours in a coffee shop in what quickly became known as the Sydney siege, which culminated in the deaths of two hostages as well as Monis. Both during and after the hostage standoff, considerable attention focused on Monis’ Islamic ties and purported religious extremism. Yet far less note was made of his extensive history of violence against women. At the time of the standoff, he was out on bail for charges relating to the murder of his ex-wife, whom he had also threatened and stalked, and he had been charged with more than 40 sexual assault offenses dating from 2000 and allegedly involving seven different women. As Clementine Ford aptly observed, this information “paint[s] an incredibly disturbing picture of someone with a deep and aggressive hatred for women.” Yet this disturbing pattern of violence against women apparently failed to raise the kind of red flags that would have led to confinement—or at least closer supervision—of Monis.

We need to stop seeing these various manifestations of misogyny—aggression, stalking, domestic violence, sexual assault—as a separate species of problem. Certainly men who engage in violence against women often do so for gendered reasons. Sometimes men are angry when women don’t obey them. Sometimes men feel that women owe them something. And women often suffer when they don’t act the way men want them to. But the consequences of misogyny and gendered violence don’t stop with women.

Unsurprisingly, research has linked violence by men against women with other antisocial behavior. Researchers have long known that those who abuse their domestic partners are also more likely to abuse children and animals. While some perpetrators of domestic violence limit their violence to family members, research has shown that many others engage in violence in the community at large. Another study found that 68 percent of men in a sample of batterers exhibited other “problem behaviors,” such as fights, previous arrests, or drunk driving.

Given the clear connection between private and public acts of violence, the relative lack of media attention to Brinsley’s attack on Thompson is inexcusable. Although local media and Twitter linked her shooting to that of Liu and Ramos within a few hours, many mainstream media outlets failed to mention her or devoted only a single sentence to her shooting until much later.

Imagine if the media focused on violent misogyny rather than ignoring it. What if the media described Brinsley’s shooting of Thompson without mentioning that he murdered two police officers? Or what if the media had reported extensively on Monis’ history of violent misogyny with no mention of his Islamic faith? I pose these hypotheticals not because I think that the media coverage should have taken that form, but rather because it is telling that such coverage is utterly unimaginable.

Certainly ending violence against women is a worthy aim in and of itself. But we also need to see misogyny as a warning sign both of violence against women and of violence, period. What if Seung-Hui’s stalking behavior had resulted in concrete punishment? What if Rodger’s aggression toward women had been taken more seriously? What if the various charges against Monis had been deemed sufficient to warrant his incarceration prior to trial?

Of course, taking gendered violence seriously is not a panacea. It’s not yet clear whether treating Brinsley’s shooting of his ex-girlfriend as a mere domestic dispute delayed the police in discovering his deadly intentions. Perhaps handling the event differently would have prevented the tragic deaths of Liu and Ramos. Perhaps it wouldn’t have.

What is clear is that gendered violence is often a prelude to other forms of violence. Moving forward, we should treat gendered violence as real violence, and its harms as part of a pattern that affects all of us.