For the past three years, I have been defending a book I wrote titled Supreme Myths: Why the Supreme Court Is not a Court and Its Justices are Not Judges. I was not saying partisan politics drives the court (though sometimes it does). Instead, I argued that the court is not a court because the justices as a group don’t now and never have taken law seriously enough to warrant calling them “judges.” Sure, they wear black robes and they sit in a courtroom, but that is not enough to make them judges. Taking law seriously—as opposed to making decisions based mostly on personal values—is what distinguishes judges from other political officials. On that basis, Supreme Court justices are simply not judges.

This idea is not liberal or conservative, Republican or Democrat. Since 1803 the Supreme Court has not taken prior law (cases, statutes, history) seriously. That has been the case whether it was the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse of the 1930s striking down progressive economic legislation, the liberal Warren court of the ’60s issuing broad personal liberties decisions like Miranda, or the Roberts/Kennedy court of today giving us mostly a pro-Republican, pro-big-business constitutional jurisprudence.

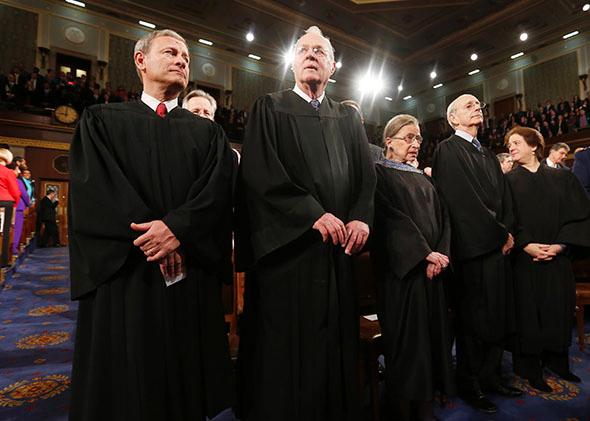

Most law professors and Supreme Court commentators accept that personal values drive the justices to a great degree, but they have nevertheless resisted taking the step I wanted them to take. That step is to recognize that we have unelected, life-tenured politicians masquerading as judges, making important decisions that affect us all. It is important to recognize the court for the purely political institution it is, and to acknowledge that it is not a court of law, in order to have a serious debate about a number of other issues. Those issues include the way the court should do its job, the matter of judicial life tenure, whether there should be cameras inside the court, and what the nomination process should look like.

If the justices really did act like judges, then perhaps our current judicial system would make sense. But given the reality, it is time to reconsider life tenure, ask the justices to perform their jobs with much more humility, place cameras in the court, and institute a nomination process in which senators demanded real answers to hard questions.

I am glad to report that a few of our most prominent scholars, court commentators, and even judges are coming around to my way of thinking about the court. Judge Richard Posner, an outspoken judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit and the most cited legal scholar of the last 20 years (and a regular contributor to Slate), was asked whether he regretted never being a justice. He answered: “Well, I don’t like the Supreme Court. I don’t think it’s a real court.”

Posner’s book How Judges Think argues at length that, at most, the Supreme Court is a “political court” different in degree than other courts for many reasons, including that it defines its own caseload, picks the most politically charged cases, and pretends to make decisions based on vague text and contested history, when in fact what the justices are doing is deciding cases based on their personal values. He calls it a “political court,” whereas I say it is not a court at all, but the difference is largely a semantic one.

Linda Greenhouse, the former New York Times reporter who covered the Supreme Court for decades, is also coming around. In response to the court deciding to hear the latest political (dressed up as legal) challenge to the Affordable Care Act, she wrote a column in the Times about how unusual it was for the court to decide to hear the case even though there was no split in the circuit courts on the issue. After calling the grant “a naked power grab by conservative justices,” she wrote the following:

In decades of court-watching, I have struggled—sometimes it has seemed against all odds—to maintain the belief that the Supreme Court really is a court and not just a collection of politicians in robes. This past week, I’ve found myself struggling against the impulse to say two words: I surrender.

Greenhouse is not the only one struggling. While the first challenge to Obamacare was pending, Dahlia Lithwick of Slate said to me that if the Supreme Court accepted the ludicrous commerce clause challenge to the requirement in the law that all Americans must buy health insurance, she would “eat your book.” After all, health care and health insurance represent a trillion-dollar industry affecting the commerce of every state. How could the act not be a regulation of “commerce among the states”?

The Supreme Court held that the mandate was not a regulation of commerce, and I waited for the email I knew was coming. Because the court upheld the mandate as a tax (even though both the president and Congress said it wasn’t a tax), technically Lithwick didn’t have to fulfill her promise. Fair enough. But that technicality misses the point. Under any reasonable interpretation of prior law, the mandate was a valid regulation of “commerce among the states.” What it wasn’t was a tax. The Supreme Court held just the opposite because of a complicated blend of personal and political (not legal) values held by the justices and the need for a five-vote majority.

I do not claim the court always acts like Republicans or Democrats. I do claim the justices don’t act like judges bound by prior law, precedent, interpretive canons, or constitutional theory. The challenge to the mandate was just one more piece of evidence for that proposition, and the latest challenge, the one that is bothering Linda Greenhouse so much, is not different in kind than the first one.

Finally, if you still don’t believe me that the court is not a court, believe Justice William Brennan, who famously used to tell his law clerks that the most important “law” at the Supreme Court was the “Rule of Five.” He would constantly remind them that it takes five justices for the court to reach a decision and they should never forget it. That vote-counting truism is the most accurate description of the law a member of our Supreme “Court” has ever uttered, and it has nothing to do with how justices or judges should decide cases. It is also just about all you need to know to understand the current debate over the new ACA cases.