In 2003, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy penned a great gay rights opinion in which he ruled that no state may constitutionally criminalize gay sex. The case dealt with two men, John Lawrence and Tyron Garner, who, the court informed us, were arrested while having sex in Lawrence’s apartment. In overturning the conviction, Kennedy slammed the state for degrading the “dignity” of Lawrence and Garner’s intimacy and relationship, describing their sex act as “but one element in a personal bond that is more enduring.”

But there’s a problem with these statements. Lawrence and Garner weren’t really having sex when the police entered the apartment. They weren’t even in a relationship. Kennedy rested his holding on fabrications—but through the power of the court, those fabrications were woven into law.

How could a Supreme Court justice be suckered into believing a set of facts with no bearing in reality? Actually, it happens pretty often. As Adam Liptak’s recent investigation illustrates, many of the justices have rather poorly calibrated bullshit detectors. Justice Samuel Alito recently cited a statistic about employee background checks that is, by most accounts, made up; Kennedy has relied on his intuition to assert that “an increasing number of gang members” are entering prison. Even Justice Stephen Breyer, whose usual fact fixation has led him to affix epically long appendices to multiple opinions, has gotten a little lazy, once citing a statistic that originated on a blog that has since been discontinued.

One possible culprit for the court’s sloppy fact-finding is the sudden profusion of amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) briefs. These briefs, written by third-parties with interests in the case, were once fairly limited; today, a high-profile case can draw dozens or hundreds of them. (Scores of groups filed amicus briefs in United States v. Windsor, from ex-gays to ex-ex-gays.) Nowadays, writing amicus briefs is nearly a profession in itself, as nonprofits, for-profits, cities, states, congressional representatives, and law professors compete to sway the court in their direction. Given the authors’ vested interest in a particular outcome, a number of these briefs are high on ideology, not so high on strict factual rigor.

Occasionally, an amicus brief will make a significant impact on the justices’ thinking. In the landmark case Grutter v. Bollinger, swing vote Justice Sandra Day O’Connor seemed drawn to support affirmative action based on the now famous “green brief,” an amicus filed on behalf of several retired military officers who supported the practice for the sake of diversity. But most amicus briefs languish in obscurity, skimmed and tossed aside by the justices’ clerks.

I asked one former clerk what role amici play in decision-making and opinion-writing on the court. (She asked to remain anonymous; clerks, who are trusted with some sensational behind-the-scenes information, pride themselves on being a tight-lipped crew.)

“Most of these briefs are just not helpful,” she told me. Many, indeed, are slapdash and downright superfluous: Some amici are “just weighing in to create a bigger stack of amicus briefs,” under the theory that “if you have a taller pile of amicus briefs, you win the case.” Ultimately, clerks pick the two or three best briefs for their justice’s perusal—usually the most evenhanded, thorough, and thoughtful ones—and chuck the rest.

If justices aren’t leaning on amicus briefs when deciding how to cast their votes, what about when it comes to writing their opinions? Most justices rely on their clerks to pen a first draft of their rulings; don’t these overworked clerks sometimes borrow ideas and phrases from the stack of amicus briefs before them?

“Very minimally,” the former clerk told me. “If you compare amicus briefs to Supreme Court opinions, you’re not likely to find very much cribbing. Clerks don’t sit down with amicus briefs and follow what they say. Could it ever happen? Sure. But not as a general matter.”

I asked the former clerk how phony facts still wind up in opinions. She told me a justice may sometimes “list a fact or list a statement from an amicus brief as support” of his or her proposition without double-checking its veracity. But these occurrences are rare; the court has a renowned law library all to itself, and justices generally direct their clerks to verify any facts that bolster their holdings. When a fake fact does find its way into an opinion, it’s usually minor and unremarkable. The examples in Liptak’s New York Times article, the former clerk noted, “didn’t move me.”

But the court does occasionally rely on truthiness, and there is a sinister underbelly to their cognitive biases. Justices already set on a particular ruling may contort facts—outside data, or even facts about the case itself—to support their judgments. In perhaps the most infamous example of this chicanery, Kennedy wrote in Gonzales v. Carhart that abortion may sometimes be banned to make women comprehend their “ultimate” role as mothers. In support of this proposition, Kennedy held that “some women come to regret their choice to abort the infant life they once created and sustained.” How does he know? A study? A poll? In fact, Kennedy admitted that “we find no reliable data to measure the phenomenon.” (One reason he couldn’t find any reliable data: That “phenomenon” is nothing more than a chauvinistic shibboleth, as most women don’t regret their abortions.) The court, in other words, couldn’t locate a real rationale for restricting abortion—so it had to make one up.

Alito recently adopted Kennedy’s sexist magical thinking in his misogynistic Hobby Lobby opinion. Throughout the ruling, Alito callously dismisses the needs of Hobby Lobby’s female employees, instead lavishing praise on its owners’ devout Christianity. The company’s founding family, Alito writes, “have religious objections to abortion, and according to their religious beliefs the four contraceptive methods at issue are abortifacients.” Apparently, those five words—“according to their religious beliefs”—are enough to convert fiction into fact, because the contraceptive methods in question are absolutely not abortifacients. Alito dismisses the science, shrugging that “it is not for us to say that their religious beliefs are mistaken.”

When justices pull these sleights of hand, their dissenting colleagues rarely call them on it; they may, after all, need to perform the same trick in the future. But every so often, a justice faced with obviously mangled facts will snap. In the 2011 case Michigan v. Bryant, the court held that a statement made to police by a dying man, Anthony Covington, could be admitted into evidence at a murder trial. (The prosecution was especially keen to use the statement, since it implicated the person who supposedly killed Covington.) Because Covington couldn’t testify at the trial himself—he was, after all, dead—his words would usually be barred as hearsay. But the court carved out an exception for declarations made solely “to enable police assistance to meet an ongoing emergency.” Because Covington’s statements were made in the midst of a possible murder spree, the court held, they weren’t formal “testimonial” and could thus be presented at trial.

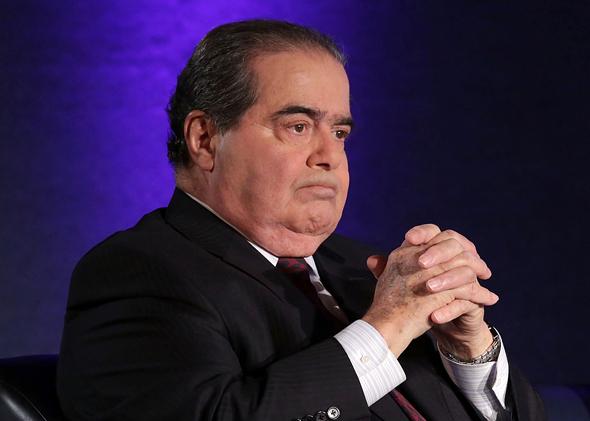

In a jaw-dropping lone dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia ripped the court’s facts to shreds. “Today’s tale,” Scalia wrote, “is so transparently false that professing to believe it demeans this institution.” Of course the police interrogated Covington for the purpose of “obtaining and preserving evidence,” Scalia scoffed; the court’s conclusion to the contrary is “patently incorrect.” The majority’s rebranding of a professional interrogation as a simple off-the-cuff Q&A constituted, to Scalia, a “vain attempt to make the incredible plausible.” Closing out his 17 pages of pure venom, Scalia hissed that “today’s opinion falls far short … short on the facts, and short on the law.”

It’s refreshing to read Scalia defending facts so vehemently—but the justice is not always so faithful to reality. When the court ruled on a complex DNA patent case, Scalia wrote separately to note that he wasn’t sure the details of “molecular biology” comported with his own beliefs. He also signed on to both Kennedy’s muddled anti-abortion cri de coeur and Alito’s Hobby Lobby disaster, suggesting that he’s perfectly comfortable with made-up facts when they lead him to a result he favors.

We shouldn’t be surprised. In any other field, and in any other court, manipulating the facts to bring about a certain result would be verboten, even scandalous. But the Supreme Court is the final authority on any legal question it chooses to resolve. It has the luxury of basing its holdings on blatant falsehoods—which then become binding on every lower court in the country. Astronomer Neil deGrasse Tyson says, “The good thing about science is that it’s true whether or not you believe in it.” The Supreme Court flips science on its head: The court’s decision is the law of the land whether or not it’s true. What other institution can turn lies into lived reality? For most of us, the truth can’t be whittled down to fit our worldview, and reality isn’t optional. But at our infallible Supreme Court, the truth is what the justices say it is.