You are no doubt as excited as I am about the advent of Constitution Day, which explodes into being again Wednesday, Sept. 17, with its customary flurry of greeting cards, traffic-stopping parades, fraught and complicated holiday dinners with the family, and, of course, a visit to the children from the Constitution Day Platypus, bearing, as she inevitably does, a cunning little basket of chocolate bills of attainder.

What’s that? You say you’ve never heard of Constitution Day™, a federally mandated holiday. Well, that is probably because it’s only been a federally mandated holiday since 2004, when Sen. Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia invented it in much the same fashion that all of our greatest national festivals have come about: He tucked it into a massive appropriations bill. The relevant rider of the Omnibus Spending Bill of 2004 amended Title 36 of the United States Code (Patriotic and National Observances, Ceremonies, and Organizations) by substituting “Constitution Day” for “Citizenship Day.”

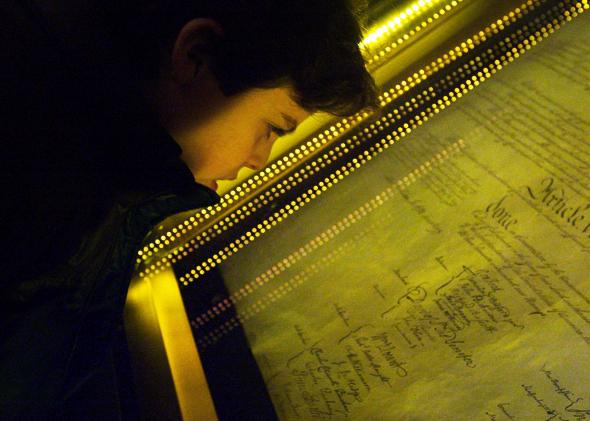

Constitution Day commemorates the signing of the U.S. Constitution on Sept. 17, 1787, and also celebrates “all who, by coming of age or naturalization, have become citizens.” The law itself provides that all educational institutions receiving federal funds—which means virtually all of them—must offer up some sort of educational program about the Constitution. It also requires that the head of every federal agency offer each employee educational and training materials about the Constitution on that day. If Constitution Day falls on a weekend, as it did in 2005, 2006, and 2011, it is observed on the contiguous weekday.

Now, mandating the nationwide teaching of the document that protects the most fundamental American freedoms may itself be unconstitutional, as Nelson Lund and the Heritage Foundation noted back in 2006. But, of course, that is just one of those idiosyncratic things that makes the holiday so special, and the Constitution Day Platypus so compelling. More interesting is the fact that nobody is completely certain who is observing this holiday, or how. Nor can anyone say whether the important goal of civics education (which has all but disappeared from the public schools in their race to teach math and reading) is being served by a day devoted to teaching the Constitution, in some fashion, in some places. In 2005, when the law first went into effect, massage schools and cosmetology programs evidently flew into a collective panic over how to meet its requirements.

And since the holiday may well run afoul of the spirit of the 10th Amendment—which generally precludes the federal government from dictating what the states may teach in schools—there is no required curriculum for Constitution Day. It seems to be sufficient for schools to fashion their own festivities with at least some nod to the history and text of the document. In truth, it’s not at all clear that all schools or federal agencies comply, as they seem to be on a kind of honor system to develop and implement their Constitution Day programs. Some children dress in red, white, and blue and pose for photos, some perform plays or stage debates, and some screen the classic Schoolhouse Rock segment about the Constitution. Doubtless someone is out there teaching Zumba to the Bill of Rights in order to protect his or her institution’s federal funding. Worthy efforts, although many educators dislike Constitution Day because a single day a year is no substitute for the massive failure of civics education in our public schools.

The history of Constitution Day can apparently be traced all the way back to Arthur Pine, head of a big New York PR firm, who seems to have invented something called “I Am an American Day,” largely in order to promote a new song, called, unsurprisingly, “I Am an American,” by a bandleader called Gary Gordon. In 1939, William Randolph Hearst, the head of a massive publishing empire, helped pressure Congress to name the third Sunday in May, “I Am an American Day.” Hearst sponsored a 16-minute film, entitled I Am an American, which was featured in theatres and became a massive hit in 1944. But it was the mayor of Louisville, Ohio, who, in 1952, designated Sept. 17 as Constitution Day, at least in Louisville. In 1952, Congress passed a new law moving the date of “I Am an American Day” to Sept. 17 to commemorate “the formation and signing, on September 17, 1787, of the Constitution of the United States.” The event was designated “Citizenship Day” when, in 1953, the Senate formally embraced the week of Sept. 17–23 as Constitution Week to commemorate the signing of the Constitution. It was all still designated as Citizenship Day until Byrd changed it to “Constitution Day and Citizenship Day.”

In 2011, Tea Party groups attempted to “adopt” local public schools and provide them with Constitution Day materials created by W. Cleon Skousen, author of the 5,000 Year Leap, whose views of slavery were controversial, to say the least, drawing from discredited sources that suggested that the real victims of slavery were the slaveholders themselves. Despite the fact that history had all but passed him by, Glenn Beck adopted Skousen as the founding father of Tea Party Constitutionalism. The Tea Party Constitution Day curriculum thus emphasized Skousen’s strange views on states’ rights and taxation and contended that the framers of the Constitution were deeply interested in enmeshing church and state. The perversity of using a federally mandated holiday, which conditions funding of education on teaching a specific piece of history, in order to promote states’ rights may have escaped them. The fervor all seems to have died down for reasons that have nothing to do with any lack of continued enthusiasm for enmeshing church and state.

Questions about how to solemnize Constitution Day sometimes prove far more interesting than Constitution Day itself. And since it’s become something of an elaborate prisoner exchange program, whereby weary law professors and legal advocates fan out across the land, crisscrossing in the sky or at airport terminals in order to speak at one another’s Constitution Day events, you might see a small uptick in the number of tiny little Fourth Amendment protests taking place at the we-can-see-you-naked machines at the TSA security checkpoints.

But before you knock Constitution Day for being a drop in the bucket of the ocean of confusion around government, civics, and the law, recognize that a probably unconstitutional holiday inspired by a PR man to peddle a song, promoted by a newspaper magnate with a blockbuster movie, and then tucked into a massive omnibus bill by a determined senator from West Virginia who carried a copy of the Constitution in his pocket every day of his public life, might just be the most American holiday of all.