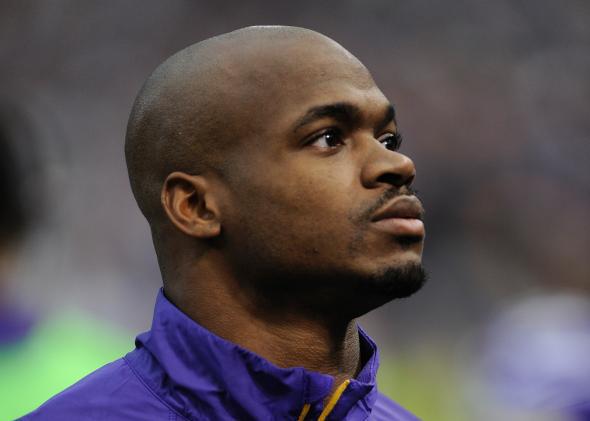

On Friday, Minnesota Vikings running back Adrian Peterson was indicted in Texas for injuring a child. According to the police report, Peterson’s son had shoved another of his children off a motorbike video game. In response, Peterson snatched a tree branch, picked off the leaves, and whipped his son on the legs, ankles, back, buttocks, and scrotum. According to the son, Peterson shoved leaves in his mouth during the whipping; Peterson’s son also said this kind of beating had occurred before.

But don’t expect Peterson to go to prison any time soon. It’s not at all clear that Peterson’s whipping broke the law. In fact, in much of the United States, beating your own children—even to the point of bodily harm—is perfectly legal.

The notion of child abuse as a distinct crime is a fairly recent invention. Through America’s first century, parents were left to raise their children as they saw fit. Corporal punishment—spanking, whipping, even battering—was widely accepted; prosecutors only intervened when they felt parents engaged in “wanton and needless cruelty.” (One father charged for such “cruelty” in 1869 had doused his blind son in kerosene then locked him in a frigid cellar for several days in the dead of winter. He was fined $300 and received no jail time.) But any punishment that fell short of blatant barbarism was generally considered a private matter.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, the law began to shift. Widespread maltreatment of children in New York’s squalid tenements led to early iterations of child protective services, which then began to spring up across the country. Initially, these services focused on saving children from neglect, providing them with shelter and nutrition when their own parents could not. But neglect and abuse often went hand-in-hand, and by the 20th century, child protective services were also tasked with rescuing children from potentially life-threatening abuse.

It was not until the 1960s that the concept of child abuse began to appear on most middle-class families’ radars. In 1962, a spate of articles—first in academic journals, then in popular magazines—brought child abuse to the attention of mainstream America. The most famous of these articles, “The Battered-Child Syndrome,” shocked millions of Americans by implying that their routine disciplinary practices might actually be deeply harming their children. Child abuse, the authors noted, occurs not just in slums but also “among people with good education and stable financial and social background.” The subtext of the line was clear to parents who engaged in casual spanking and whipping: This means you.

Legislatures across the country responded to the new research by explicitly criminalizing child abuse. But the new laws generally prohibited only “serious” bodily injury—with the understanding that traditional punishments like spanking and smacking would remain a parental prerogative. In the 1970s, legislators shifted their focus to child sexual abuse, a once nearly invisible horror that, by the end of the decade, was seen as the chief threat to children’s well-being. Americans began to fixate on the savagery of molestation, and the laws regarding non-sexual abuse remained fairly constant. Today, it’s still largely true that parents can beat their children as punishment so long as they don’t inflict dangerous, long-term physical damage.

Though the laws regarding child abuse have stagnated, the research certainly hasn’t. In recent years, scientists have found that even spanking—the most widely accepted and allegedly humane form of corporal punishment—has alarmingly negative consequences for childhood development. Spanking can increase a child’s risk of aggression, antisocial behavior, and mental health disorders later in life. It slows cognitive development and decreases language skills. Spanking may not leave outward signs of injury. But the mental scars it inflicts can last a lifetime.

Not a single legislature in the United States, however, has outlawed spanking in the home—and 19 states still permit corporal punishment in schools, a practice the Supreme Court condoned as constitutional in 1977. More troublingly, most states’ child abuse statutes are broad enough to allow an array of corporal punishment. The Texas statute under which Peterson was charged criminalizes “bodily injury” to a child “recklessly, or with criminal negligence.” But Texas courts have held that parents may still physically punish their children with a limited degree of force when such punishment is “necessary to discipline [the] child or to safeguard or promote his welfare.”

When is force “necessary to discipline” a child? That’s up to the jury. And juries in Texas have interpreted the statute rather generously: Parents who slap or whip their children in what might be deemed the “traditional” way tend to get off scot-free, while Texas courts have clarified that spanking only violates the statute when it’s committed with an intent to cause serious bodily injury. Only parents whose cruelty truly shocks the conscience are convicted under the statute; one father was imprisoned after whipping his daughter with a dog leash, while another was sentenced to 10 years in prison after spanking his children so hard with a wooden oar that it broke on their buttocks.

It’s impossible to know, of course, whether a jury will find the beating Peterson administered to be acceptable discipline or child abuse. But current case law gives Peterson reason for optimism. The way he punished his son probably isn’t the kind of thing the Texas legislature meant to criminalize. Parents have done this kind of thing to their kids for centuries. Such a “whooping,” as Peterson put it, might shock your conscience. But that doesn’t mean it’ll shock the conscience of a Texas jury.

Peterson’s case reveals a broader problem with America’s child-abuse laws: It’s surprisingly difficult to tell where legal corporal punishment ends and criminal child abuse begins—and so long as the former is allowed, the latter seems bound to occur. The fear of overlap between physical discipline and illegal abuse is part of what spurred Sweden to outlaw corporal punishment, including spanking, in 1977. Since then, nearly 40 countries have followed suit. But physical punishment remains legal in every single U.S. state.

That doesn’t seem likely to change any time soon. In 2007, lawmakers in Massachusetts, Wisconsin, and California briefly considered anti-spanking bills, but the attempts quickly fizzled following widespread outrage. In 2012, Delaware did pass a law tightening restrictions on corporal punishment in the home by forbidding parents from inflicting “physical injury to a child through unjustified force.” Although the bill’s sponsors repeatedly explained that spanking would not qualify as “unjustified force” under the statute, some parents still complained, claiming that the law amounted to a spanking ban. By far the most vocal proponents of corporal punishment in America are conservative Christians, some of whom believe that the Bible verse about the rod should be taken literally. To these Christians, physical discipline is a necessary component of raising children.

So extreme is conservatives’ support of corporal punishment, in fact, that Senate Republicans have repeatedly blocked America’s ratification of the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child. The treaty is designed to stop child trafficking, prostitution, and pornography, as well as the use of children in military conflicts. But conservatives believe that it would also outlaw spanking. This is unlikely, given that scores of countries that practice corporal punishment have signed without a conflict. But American conservatives seem to have successfully made their case against the treaty to the two-thirds of Americans who spank their children. (Only two countries in the world have not ratified the treaty: The United States and Somalia.)

If America is so enamored of spanking that it can’t ratify a treaty to prevent child trafficking, there’s little chance right now of even blue states ending corporal punishment. That means that, for the foreseeable future, we’ll be stuck with cases like Peterson’s, where 12 strangers in a jury box will have to decide whether you beat your child within the confines of the law. That’s a grim task, and often an impossible one. But unless we’re willing to declare that beating children has no place in a civilized country, the line between discipline and child abuse will remain dangerously blurry.