Of all the narratives coming out of Ferguson, Missouri—the militarization of local cops, the racial disparities in the criminal justice system, the acceptable uses of force—the constitutional story that has most captured our attention is that of the police persistently violating the First Amendment rights of both the protesters and the press. When we talk about constitutional violations there, we do so primarily with respect to our freedom of speech and assembly.

Now it is beyond dispute that what the media is doing in Ferguson is vitally important and that the arrest and incarceration of reporters is a scandal. And there is no denying that we learn something important about the scale of police lawlessness when they cross the line into arresting journalists, who are traditionally off-limits. It is also indisputable that the right of protesters to peaceably assemble and speak is being undermined by mass arrests, curfews, and attempted news blackouts. But search for the words unconstitutional and amendment in Ferguson coverage on Google, and the extent to which our outrage seems to begin and end at the First Amendment is quite striking. Searching Google News (admittedly not a scientific method, but pretty good), we got six times as many results on Ferguson coverage that mentioned the First Amendment as mentioned the 14th Amendment, which is the amendment that covers a wide range of police abuses having nothing to do with freedom of speech.

A number of superb articles detailing the dangers of suppressing speech and dissent have illuminated the problem of police crackdowns on the First Amendment. And this week the ACLU, NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law published a joint letter calling for the end of the curfew in Ferguson because it “suspends the constitutional right to assemble by punishing the misdeeds of the few through the theft of constitutionally protected rights of the many.”

Far fewer articles describe the other constitutional violations taking place on the streets of Missouri, and those violations are every bit as urgent as the infringements on speech and assembly. We’ve seen very little coverage of the use of tear gas and rubber bullets as constitutional violations. But the due process clause bans the police from using excessive force even when they are within their rights to control a crowd or arrest a suspect. And tear gas is in a category all its own. Not only is unleashing it into a crowd an unconstitutional exercise of excessive force, but its use is banned by international law. That’s one of the reasons Amnesty International sent a team of investigators to Ferguson. Similarly, the use of rubber bullets under the circumstances is also unconstitutional. Some kinds of rubber bullets are more unconstitutional than others, because certain types are more likely to injure and maim.

But excessive use of force is only the beginning. Pulling people out of the crowd and arresting them without probable cause (or for being 2 feet off the sidewalk) violates the Fourth and 14th Amendments, particularly when those arrests are disproportionately of black protesters. The general arrest statistics in Ferguson reveal what looks to be a stunning constitutional problem. According to an annual report last year from the Missouri attorney general’s office, Ferguson police were twice as likely to arrest blacks during traffic stops as they were whites. Emerging reports about racial disparities in Ferguson’s criminal justice system and the ways in which the town uses trivial violations by blacks to bankroll the city (and disenfranchise offenders) all represent constitutional questions. Why don’t we characterize them as such? These are not just violations of the law or bad policy. These are violations of our most basic and fundamental civil liberties.

Of course, probably the biggest potential constitutional violation of all—and eyewitness testimony suggests this as a real possibility—is the alleged use of excessive force by the police in shooting an unarmed 18-year-old at least six times. Under the law, each of those bullets must be separately justified, as necessary, even if one believes the officer’s story that Michael Brown rushed him. To be sure, the news media has covered this, but very few of us talk about the shooting as a potential violation of the Constitution. Remember, the Constitution is the foundational bargain between the people and their government, the framework on which our legal order rests. When we fail to talk about the arrests, searches, racial profiling, and government brutality in constitutional terms, we are failing to capture how profoundly the state has betrayed its promises.

Howard Zinn famously said: “The First Amendment is whatever the cop on the beat says it is.” But as a former public defender told one of us on Wednesday, precisely the same thing is true for the Fourth Amendment, the Fifth Amendment, and the Eighth Amendment, as well as a lot of the rest of the Bill of Rights. We ignore those other constitutional violations at our peril.

This past term, the Supreme Court found it extremely easy (and in fact unanimously agreed) to see that a police’s warrantless search of a cellphone is unconstitutional. More than one commentator observed that it was very easy for the justices to find a constitutional affront here because they all have cellphones and can imagine how intrusive a police search of those phones would be. But it’s much harder for the courts, and even sometimes for the press, to imagine a lifetime of aggregated constitutional violations, from stop-and-frisk policies that disproportionately affect people of color, to civil forfeiture laws and the “war on drugs” that do the same.

One need look no further than the current Supreme Court to understand that the First Amendment now plays an outsize role in the national constitutional conversation about everything ranging from money in politics to maintaining order around health clinics to limiting the reach of public-sector unions. And given that the First Amendment is—in Pac-Man fashion—beginning to swallow up all the rest of our doctrine, perhaps it’s no surprise that we see the First Amendment dominating the conversation on the ground in Ferguson as well. We all like to speak, regardless of race and income. And suppression of speech is something that offends all of us across race, gender, and economic lines. But what about those other provisions, the ones that protect prisoners and criminals and people who steal cigars? They are far more abstract for many of us.

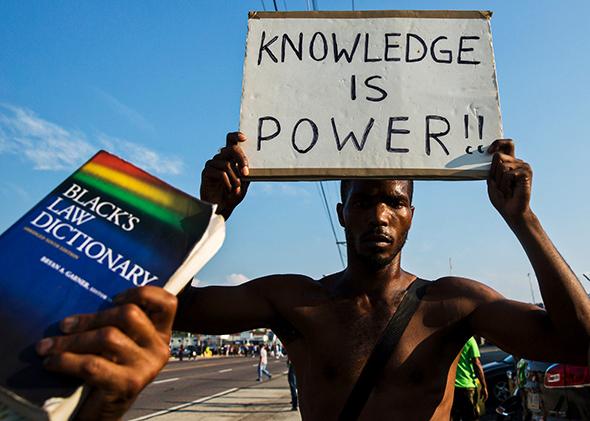

Of course, one could argue (as has legal luminary Burt Neuborne) that the First Amendment is first for a reason. How else can we publicize the other constitutional violations in Ferguson if we cannot speak and share them? The right of free citizens and the press to film what they see and disseminate it widely is central to the efforts to correct the other, more systemic and entrenched race and economic violations that have made Michael Brown’s killing a national story. Stephen Wood, a protester in Ferguson, made precisely this point to the Los Angeles Times: “When people are oppressed and they want to be heard, they go to an extreme,” he said. “What good is the Constitution; what good are these laws if we don’t use them?”

At the same time, it feels as though the relentless focus on First Amendment suppression—the focus on what happens when the sun goes down each night and the protesters and cops face off—has taken our eyes off the other equally meaningful constitutional affronts and has distracted us from the deeper conversations about the ways that racial profiling, discrimination, and outright brutality need to be addressed. Ferguson will not be a freer, better, or more just place when the protesters are allowed to gather without cops in riot gear down the block. It will be the same constitutional nightmare it has evidently been for years. We need to expand our vision of what is a constitutional violation to include what happens when the cameras roll out of town. Because even when the world stops watching, Ferguson and all the Fergusons across the country will need a lot of constitutional protection.