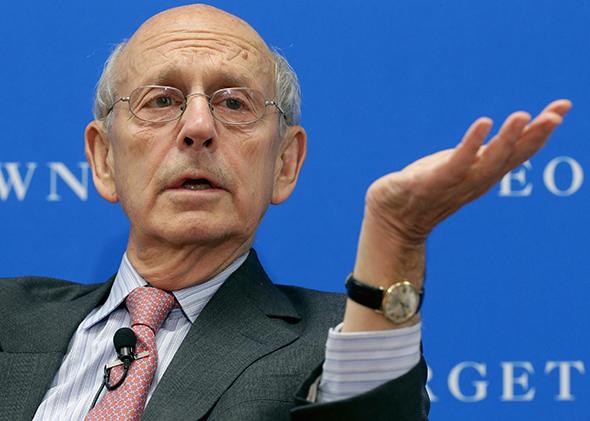

When a justice is in the minority on the Supreme Court, as Justice Stephen Breyer has long been, there aren’t many opportunities to write truly landmark opinions. Those are the spoils of the majority, or at least of Anthony Kennedy. Yet Breyer found himself writing for a surprising majority this term in NLRB v. Noel Canning, which held unconstitutional recess appointments made by the president when the Senate was still in pro forma session. While media accounts of the decision understandably emphasized how it was a loss for the president, Breyer’s opinion is about a far more important and enduring question than the lawfulness of these handful of recess appointments: How should courts interpret the Constitution? As has always been the case, the answer to this deeper question will shape judicial rulings across the spectrum of constitutional law issues, from gay rights and states’ rights to God and guns.

In his opinion, Breyer offers the most forceful defense of what’s often termed “living constitutionalism” to appear in a majority Supreme Court opinion in a generation. Rejecting Antonin Scalia’s 18th-century approach of originalism—in which all that matters is what the framers thought—Breyer in Noel Canning stakes a bold claim for interpreting the Constitution “in light of its text, purposes, and our whole experience.” His is a progressive vision of the Constitution, one articulated previously in his books, like Active Liberty, and in various concurring and dissenting opinions he has authored over the years. But now, in the wake of Canning it is also the opinion of the court. As a result, it will influence how future courts—state and federal, trial and appellate—will apply the Constitution to answer tomorrow’s controversies.

It may seem like a niggling academic problem. But it has real-world consequences. That’s one of the reasons Justice Antonin Scalia—who agreed with Breyer that these recess appointments were unconstitutional—nevertheless disagreed with the court’s opinion so vigorously. While it may be a sign of how far the Roberts court has shifted that Scalia is forced to file his blustery dissents in the form of angry concurrences, the substance of Scalia’s complaint is unchanged: The court “casts aside the plain, original meaning of the constitutional text.” Breyer responds by saying that Scalia’s originalism asks the wrong question. “The question is not: Did the Founders at the time think about” the exact issue before the court? “The question is: Did the Founders intend to restrict the scope” of the Constitution only to the “forms … then prevalent,” or did they intend the Constitution “to apply, where appropriate, to somewhat changed circumstances”? Fidelity to the Constitution, he suggests, means using its timeless principles to address new and unforeseen situations. You know, like figuring out how to preserve privacy in an age of smartphones—as the court did this term in Riley v. California, another case decided without relying on originalism

For Breyer, the recess appointments power dramatically illustrates the advantages of his approach. Originalism, Scalia argues, requires reading the recess appointment power narrowly to apply only to formal breaks between sessions. Those were the types of recesses referred to in the dictionaries of the period, so that’s what the founders expected. Yet due to institutional changes in the Senate (more midsession breaks, shorter breaks between sessions), such a narrow view of what counts as a recess would render the whole Recess Appointments Clause, as Scalia admits, “an anachronism.” It wouldn’t have any contemporary relevance. Breyer calls out Scalia, who “would basically read it out of the Constitution.” “He performs this act of judicial excising in the name of liberty,” Breyer stings. Not content to stop there he adds: “We fail to see how excising the Recess Appointments Clause preserves freedom.”

Contrary to some of the critics of active liberty or its grandfather, evolving constitutionalism, reading the Constitution broadly in service of its “reason and spirit” isn’t a license for justices to simply impose their own values on society. Breyer grounds his understanding of the core purposes of the Recess Appointment Clause in data and evidence. To determine whether midsession breaks qualify as recesses, the former law professor surveys every single recess appointment since the founding. He wades through Senate reports and a century of presidential legal opinions. He factors in the historic practices of the comptroller general. He analyzes the recess power at key moments in history, when its scope and meaning were publicly contested. His judgment is shaped by empirical data on the average length of Senate confirmations and on the duration of recesses in which appointments have been made. He adds two appendices, one on every congressional recess and another reporting the results of a “random sample of recess appointments” under recent presidents.

Breyer’s approach to constitutional interpretation doesn’t ignore the framers; the views of Madison, Jefferson, Washington, and Marshall are all taken carefully into account. Yet he also seeks to discover how the recess appointment power has functioned and been understood since the founding—by the various attorneys general, by the Senate, and by presidents making appointments. “There is a lot of history here,” Breyer reminds us. Constitutional law, he suggests, should be informed by data as much as by dictionaries.

No theory of constitutional interpretation is “perfect”—if by that one means denying a judge any meaningful discretion over how to rule. Breyer’s leaves a number of open questions. How broadly or narrowly should constitutional principles be defined? When historic practices conflict, which take precedence? What if relevant data is unavailable? Still, Noel Canning is significant for the fact that, after 20 years on the intellectual ropes, a principles-based approach to constitutional interpretation has been so prominently endorsed by the court.

Scalia himself admits that even originalism permits of some judicial discretion. His theory, he insists, just has to be better than the alternative, invoking the analogy of two campers being chased by a bear. One asks the other, “How are we going to outrun the bear?” The other responds, “I don’t have to outrun the bear, I just have to outrun you!” After Noel Canning, it looks like Breyer’s active liberty is giving originalism a good race.

Six years ago, Scalia wrote the majority opinion in District of Columbia v. Heller, the landmark Second Amendment case that established an individual right to use handguns in the home. Scalia’s heavy reliance on founding-era history in that case led some to call Heller Scalia’s crowning achievement. Originalism, however, now has some competition. Noel Canning embraces a progressive vision of the Constitution. And that may be Breyer’s greatest legacy.