Unless you are a lawyer or a glutton for punishment, you probably want to avoid reading the new D.C. Circuit and 4th Circuit opinions reaching conflicting results on the legality of key provisions of the Affordable Care Act—the parts that provide subsidies for Americans who sign up for health insurance through the exchanges the law created. The opinions are full of jargon parsing the intricacies of the mammoth health care law. But well within the weeds of these lawyerly discussions is a more fundamental question: Is it the courts’ job to make laws work for the people, or to treat laws as arid linguistic puzzles?

At the heart of the 2–1 D.C. Circuit ruling striking down subsidies for anyone getting their insurance from a federally run rather than state-run health care exchange is a theory for interpreting statutes called “textualism.” Modern textualists view the job of courts’ interpreting statutes as puzzle solving, using dictionaries and grammatical rules known as “canons of construction” such as the “last antecedent rule.” Strict textualists generally won’t look at legislative history—records of what members of Congress said on the floor or what is contained in House or Senate committee reports, for example—to figure out what Congress intended. Just the text.

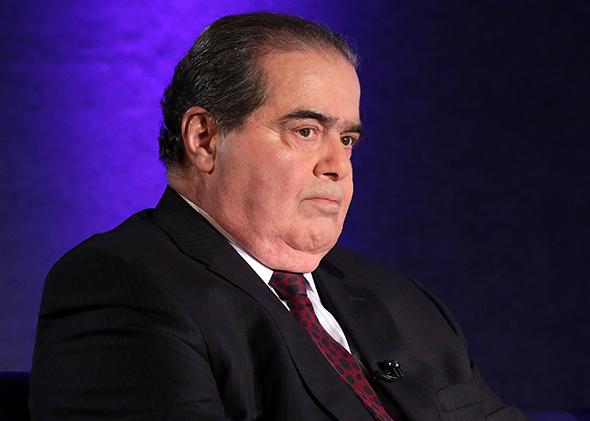

Justice Antonin Scalia of the Supreme Court is the leading proponent of textualism, an approach he justifies as required by the Constitution and better than the alternative of using legislative history. He thinks judges unreliably cherry-pick legislative history, quoting the late Judge Harold Leventhal’s quip that it’s “the equivalent of entering a crowded cocktail party and looking over the heads of the guests for one’s friends.” Before Scalia, textualism was one tool among many for interpreting statutes. But now, thanks to his relentless campaigning for the textualist approach, for many strongly conservative judges, the text is the beginning and the end of the analysis when it comes to the meaning of a statute.

Rigid textualism can lead to harsh results. Consider the 1990 case of United States v. Marshall, for example, involving the sentencing of a drug dealer who was distributing LSD. The LSD was sold on blotter paper. According to another leading textualist, Judge Frank Easterbrook of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit, the drug dealer’s sentence had to be based not only upon the weight of the LSD itself, but also the blotter paper, under a federal sentencing statute that required sentencing based upon the weight of a “mixture or substance containing a detectable amount of” the drug. Easterbrook had no problem imposing a much harsher sentence on the dealer given his narrow reading of the law, even though the weight of the paper had nothing to do with the severity of the crime. As Easterbrook just wrote in another case about statutory interpretation, “the text is what it is, no matter which side benefits.”

Dissenting in the LSD case, Judge Richard Posner, one of Easterbrook’s colleagues, explained both the absurdity and the harshness of Easterbrook’s analysis: “A quart of orange juice containing one dose of LSD is not more, in any relevant sense, than a pint of juice containing the same one dose, and it would be loony to punish the purveyor of the quart more heavily than the purveyor of the pint. It would be like basing the punishment for selling cocaine on the combined weight of the cocaine and of the vehicle (plane, boat, automobile, or whatever) used to transport it or the syringe used to inject it or the pipe used to smoke it. The blotter paper, sugar cubes, etc. are the vehicles for conveying LSD to the consumer.”

The D.C. Circuit’s Obamacare majority opinion used similar unfeeling tools of interpretation. As Emily Bazelon carefully explained, the part of Obamacare at issue provided subsidies for people who buy health insurance in exchanges “established by the State under section 1311” of the Affordable Care Act. The majority held that this part of the law excluded subsidies for people who joined a federal exchange in the 36 states that did not establish their own exchanges. This was unambiguous, the majority said, even though other parts of the law did not seem to make sense given this interpretation. And then the court refused to defer to the IRS’s reasonable interpretation that anyone in a state or federal exchange would be equally eligible for a subsidy. Courts are supposed to defer to agencies on ambiguous statutes because of their expertise and experience in implementing federal laws.

The three judges on the 4th Circuit who upheld the Obamacare subsidies, as well as Judge Harry Edwards, the dissenter on the D.C. Circuit, saw the language of the statute as less clear than the D.C. Circuit majority. And they saw good reason to defer to what they considered to be the IRS’s reasonable interpretation of the statute. But there is something more fundamental at stake.

Edwards, in his dissent, called the lawsuit a “not-so-veiled attempt to gut the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.” Judge Andre M. Davis of the 4th Circuit put it even more bluntly. He accused the challengers who sued to block the subsidies of asking the court to help them “deny to millions of Americans desperately-needed health insurance through a tortured, nonsensical construction of a federal statute whose manifest purpose, as revealed by the wholeness and coherence of its text and structure, could not be more clear.”

The 4th Circuit judges, and Edwards, were looking at the whole statute to make it coherent and to make the law work. There is a long tradition of reading statutes in this purposeful way, and a few decades ago, the opposing strict textual reading likely would not have been taken seriously. Today, however, arguments that were once considered “off the wall” are now, in Yale law professor Jack Balkin’s terms, “on the wall.”

The counterargument—that courts have an obligation to make laws work—is especially important these days, when Congress is barely working. In this time of political polarization, Congress is much less likely to fix any statutes, much less a statute as controversial as Obamacare. The judges surely know that the courts, rather than Congress, will have the last word on the statute’s meaning.

It is not a coincidence, as Emily points out, that judges appointed by Republican and Democratic presidents have divided along party lines in these cases. I do not believe this is because Republicans dislike Obamacare and Democrats like it. It is because Republican presidents now appoint judges who stick to textualism even when it leads to harsh results while Democratic presidents are more likely to choose judges who will look at the big picture and the human costs, when they’re parsing the words of a law.

Fortunately for those of us who side with the second approach, Justice Scalia’s strict textualism does not have many takers on the Supreme Court, even among his fellow conservatives. If and when these cases make it to the Supreme Court, let us hope a majority will not let the fate of the health care for millions of people rest on a chary and uncharitable exegesis.