Abolitionists have ample reason to believe a Supreme Court decision declaring the death penalty unconstitutional is within their grasp. After another botched execution this week, it must look like the day is coming ever closer.

Over the past dozen years, the court has gradually narrowed the permissible uses of capital punishment, rejecting its use for juveniles, child rapists who did not kill, and the mentally retarded. This past May, in Hall v. Florida, the court also announced that mental retardation couldn’t be determined by a hard and fast numeric rule, which Florida and other states had used to limit the impact of the court’s ban.

Those decisions suggest to court watchers that there may finally be a five-justice majority to reject the death penalty in all cases. The questions folks are asking are who are they and when will it happen. The liberal wing seems dependable. Justices Stephen Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsburg have both consistently voted against the death penalty. Last year, Justice Sonia Sotomayor dissented from the court’s refusal to hear a challenge to Alabama’s death penalty law, which allows a judge to override a jury’s recommendation of mercy. Based on Justice Elena Kagan’s vote in Hall and her legal pedigree—which includes a stint clerking for Thurgood Marshall, an outspoken death penalty opponent—there’s ample reason to believe she’d be receptive to a constitutional challenge to capital punishment as well.

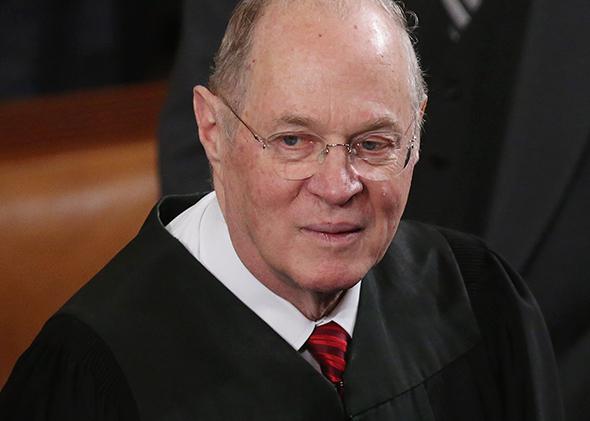

There’s also ample reason to believe that a fifth vote could come from Justice Anthony Kennedy. In fact, one could argue that Kennedy’s vote is even more dependable than the others. The juvenile case (Roper v. Simmons), the child rapist case (Kennedy v. Louisiana), and Hall, were all 5–4 decisions. In each, Kennedy both cast the decisive vote and wrote the majority opinion. Over the years, his position on capital punishment has become more principled and his rhetoric increasingly robust. In Hall, Kennedy wrote that executing an intellectually disabled individual “violates his or her inherent dignity as a human being” and serves “no legitimate penological purpose.” He has also repeatedly expressed concern with America’s international position as a grim outlier on the death penalty and, as far back as a 2003 speech to the American Bar Association, has said that he is deeply troubled by the American criminal justice system generally.

And suddenly this week, two broad-based challenges to capital punishment have been hand-delivered to death penalty abolitionists. If the court is standing by, it should be on notice that the situation on the ground is changing. Judge Cormac Carney’s decision last week rejecting the California death penalty as unconstitutionally arbitrary is remarkable. It is also a template for a Supreme Court brief seeking to abolish the death penalty nationwide. Furman v. Georgia, a 1972 decision striking down the death penalty as then practiced as unconstitutional, and Gregg v. Georgia, a 1976 decision upholding revised death penalty laws, require states to create nonarbitrary sentencing systems. Carney’s conclusion last week is that this mandate is violated by his state’s practice of executing only a random few murderers. California executes a smaller percentage of death-sentenced murderers than any other capital punishment state, but the randomness argument could be made about any other death penalty state. Capital sentencing everywhere is infected by racism and classism.

The second sign that things could be changing is Joseph Wood’s botched execution Wednesday night. It, too, lays the foundation for a compelling potential argument for doing away with capital punishment. In 2008, the court rejected by 7–2 a challenge to Kentucky’s lethal injection protocol. The plurality opinion, authored by Chief Justice John Roberts and joined by Kennedy, held that “an isolated mishap alone does not violate the Eighth Amendment.” but after Wood this week, and Clayton Lockett’s botched execution in April, it’s difficult to characterize these mishaps as isolated. They are starting to look more like the norm.

Abolitionists have other reasons to believe the lethal injection decision might be reversed or modified. Breyer’s vote with the majority in that 2008 case was tepid and based in part of the insufficiency of the evidence of suffering. Also, Kagan has replaced John Paul Stevens, who voted with the majority to uphold Kentucky’s lethal injection system.

So is the court poised with five votes to end capital punishment? Of course, Kennedy’s vote is hardly a sure thing. Wood’s lawyers asked Kennedy to stay the execution midway through the two-hour procedure. Kennedy refused. He also cast a decisive fifth vote in a 2005 case upholding Kansas’ death penalty law, which says that when a jury finds the aggravating and mitigating evidence against a defendant to be equal, the tie should go to death. Michael Meltsner, who was the first associate counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund during its litigation campaign in the 1960s and ’70s says, “I don’t think Kennedy is there yet.” One might worry, too, about Kagan, who said she accepted the constitutionality of capital punishment during her confirmation hearings.

It’s possible that the prospects for overturning the death penalty might get stronger if a Democrat wins the 2016 election and has the opportunity to replace Kennedy or one or more of the conservative justices with a more reliable vote for abolition. But perhaps a Democrat will not win, and perhaps Kennedy, who is 78, will retire and be replaced by a far more strident conservative in the mold of Justices Samuel Alito or Antonin Scalia. Kennedy’s bona fides as a critic of the death penalty and the American criminal justice system are substantial. For the foreseeable future, this is probably the best opportunity abolitionists have to end the death penalty in America.

If, as some suspect, the five votes are indeed there, the failure to press a case to the court means the death penalty could linger long beyond its natural life. If the votes aren’t there, on the other hand, pressing a case to the court could do great harm. It’s a massive gamble. The justices might say that the arbitrariness problem has been fixed and give the American public further confidence in capital punishment. If that happened, it’s hard to imagine the court returning to the issue anytime soon. One gets a crack at these issues only every 50–100 years.

Carol Steiker, the Henry J. Friendly Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, says this of the abolition gamble:

It’s a tough call. On the one hand, there’s been a stunning sea change in the use of the death penalty, including abolitions at the state level, declines in both execution and death sentencing rates, decline in public support, and powerful international pressure against the practice. Add to that the geographical isolation of the death penalty, which is used robustly in only a few states and only a few counties within those states, and it’s easy to see capital punishment as a practice that the court might deem to be marginalized and withering. On the other hand, the raw numbers aren’t as strong as they were in any of the cases in which the Supreme Court has ruled particular death penalty practices unconstitutional. If you bring a global challenge and lose, it may make it harder to succeed in the future. If you take a shot at the king, you better kill him.

So, it’s a roll of the dice, and the stakes could hardly be higher, but notably, no one’s stepping up to roll those dice. In the 1960s, Meltsner, Tony Amsterdam, and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund were in clear control of the death penalty abolition campaign. For better or worse, they determined which issues should be brought before the court and in which order. It’s impossible to imagine Furman having been won without their efforts. But today, there’s no organized abolition program and no Amsterdam or Meltsner. The gay marriage movement has Ted Olson and David Boies. The abolition campaign has no such leadership. That’s not to say no one is advocating against the death penalty or representing the interests of people on death row. They are. But no one is systematically leading the thinking about how to influence the Supreme Court through a series of challenges and cases. As Meltsner says, “The issues are far from as clear cut as they were in the 1960s,” and points to the influence of discrimination as an organizing principle. “It was easy for us in a way,” he said. “We began with race. We never left race in a way. No matter how awful the criminals were, randomness was worse because it was based on race.”

Whatever brought them and bound them to the cause, one can’t help but wish for a new Meltsner or Amsterdam to emerge. There may very well be a historic opportunity at hand. It’d be a shame if it slipped by solely for a lack of leadership.