My law school experience seemed mostly ordinary. It included only a few scary Socratic moments like those highlighted in The Paper Chase. It also included only a few doses of the frivolity reflected in Legally Blonde. But—and this was not that long ago—it also included plenty of something else: a significant exposure to the potential of our courts interpreting our Constitution to make the world a better place.

This heroic vision of our courts and our Constitution is gradually disappearing along with the generation that most believed it. Many of the professors or judges who taught my classes, or the lawyers for whom I worked in the summers, lived their early years in the law at a Supreme Court headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren; a court that sought to use constitutional law to change America in progressive ways. For at least some of these elite lawyers from that cohort—let’s call them the Warren Court Generation—the law was not just a profession, but a passion. Now, nine years after I graduated, many of that generation are retired. Others are dying. I worry that their heroic vision of our Constitution could retire with them.

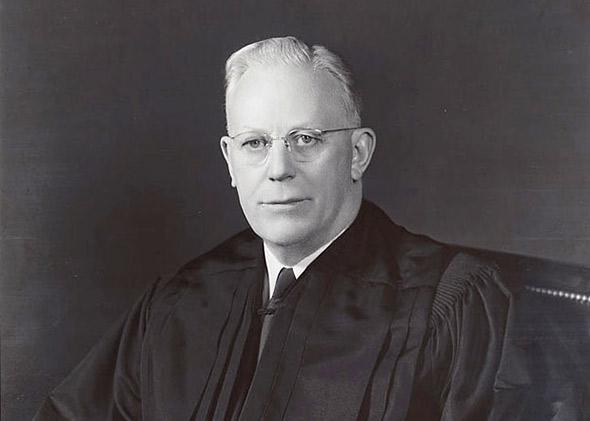

In 1954, the Supreme Court, headed by the recently confirmed Warren, decided Brown v. Board of Education, declaring official racial segregation unconstitutional. Warren retired in 1969, but scholars have argued that this period of our constitutional history continued until 1974. In that 20-year period, the court did incredible things. It changed the way we treat criminal defendants. It changed free speech protections. It changed the ways elections are conducted. It changed the way women are treated.

And during those two decades, important figures from the Warren Court Generation came of jurisprudential age. They studied these decisions in their law schools and saw how they aspired to achieve social justice. As a student essay in the Yale Law Journal stated at the time, the Warren Court “made us all proud to be lawyers.”

The Warren Court Generation went on to clerk for federal court judges who did their best to implement the vision of that court, judges like David Bazelon and J. Skelly Wright on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. The very best of them went on to clerk for the titans of the Warren Court itself, for Justices like Warren or William J. Brennan or Thurgood Marshall.

And once they started their careers, this generation occupied a central place in our national public debate about the Constitution, standing for the proposition that our courts might see in our Constitution the potential to build a better America. As Laura Kalman has documented, many of them became influential academics providing the intellectual infrastructure for this argument. Scholars like John Hart Ely (who taught at Harvard and Yale and was the Dean at Stanford Law School) and Owen Fiss from Yale Law School provided elegant theories defending the work of the Warren Court. As the problems of the Warren Court’s decisions became clear, that same Warren Court Generation used their academic writing to try to repair them.

Other members of the Warren Court Generation became federal judges on the appellate and district courts, articulating a robust vision of the Constitution’s role in promoting social justice. In the absence of a Brennan, Marshall, or Warren at the Supreme Court, judges like Stephen Reinhardt on the United States Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit became a “Warren Court in Exile.” As Reinhardt once wrote, “we must always remember that it was the Court … that for the first time gave meaning to the phrase ‘with liberty and justice for all.’”

This Warren Court Generation had some of the loudest microphones and an outsized influence in our public discussions of the Constitution, even if they never represented a real majority or plurality view. As time went on, their influence waned, and their vision became much less popular. Warren Burger, who succeeded Warren as the chief justice, decried the “young people who go into the law primarily on the theory that they can change the world by litigation in the courts.” I’ve labeled the generation of legal elites that came of jurisprudential age during this next era the “post-radical generation.” This includes our current president, who remarked during the 2008 campaign that he “would be troubled” if there was the kind of behavior today by the Supreme Court that the Warren Court Generation prized and defended.

Now this Warren Court Generation has been fading from our public debates. Some, like John Hart Ely, have passed away. Others have retired, giving retirement speeches about the Warren Court “Golden Age” they experienced that has since faded. To be sure, some still fight the good fight. Yale Law Professor Bruce Ackerman just published a landmark book on the Civil Rights Revolution. But their numbers become smaller every year.

Why does this matter? Because as these voices of the Warren Court Generation disappear, their voices are replaced by something murkier. The next generation of elite lawyers, with some exceptions, does not often push the argument that courts interpreting the Constitution can make the world a better place. It might be that this position has not convinced enough members of later generations. If you walk the halls of our law schools or the floors of our courtrooms you are likely to hear something more modest.

Or it might be that the vision of the Warren Court Generation is still accepted in private but that, as Dahlia Lithwick has noted, it must either be muted or modified if elite lawyers wants to avoid a professional glass ceiling that comes from a Senate confirmation vote. But the absence of these voices is felt most keenly at our law schools, and perhaps most keenly right now—at graduation time—when a clarion vision of progressive constitutionalism might be welcome. Law schools were once places where law students learned the technical craft of constitutional law, but also learned grand ideas from their professors that suggested our Constitution could be a tool to realize the promise of America. Law schools were optimistic places at which students were positioned to improve the world. As one law student from that time put it decades later about his law school experience, “the law seemed like a romance.”

Today’s law schools are different. Schools and students face enormous financial strains that force a discussion about the bottom line of the law rather than the social potential of the law. In that climate the very absence of that voice of the Warren Court Generation means that when discussion does turn to our Constitution, there is little sense that great things can come from our constitutional law. The romance is gone. The meter is running.

Operationally, this loss of the Warren Court Generation perspective means that we argue more and more between the 40-yard lines. We start from the premise that courts cannot and should not do anything transformative, and we argue about which less transformative things they can do. Even for gay marriage—the leading civil rights issue of our time—it fell to two lawyers who themselves lived through the Warren Court—David Boies and Ted Olson—to stand for the perspective that federal courts should take a bold step in support of gay marriage. The younger generations were more skeptical.

Ely, a former clerk to Earl Warren himself, inscribed his classic book Democracy and Distrust defending the work of the Warren Court with a telling phrase about his former boss, Warren: “You don’t need many heroes if you choose carefully.” It might just be that there are fewer and fewer of these constitutional heroes to choose from anymore.