Abortion is on trial this week in Alabama. Technically speaking, the witnesses are appearing before federal District Judge Myron Thompson to discuss a new state law that requires doctors who perform abortions to have admitting privileges at local hospitals. That sounds reasonable, I know, but it isn’t, and it’s also not what’s at stake. This trial is about whether poor women in red (and even purple) states will continue to have access to abortion, or whether some states will succeed in shutting down every clinic within driving distance, all in the name of protecting women (from themselves).

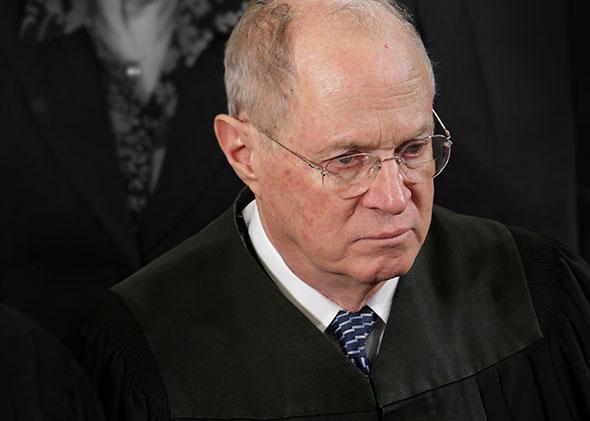

We’ve reached the Rubicon, and if we cross it, abortion clinics will disappear from parts of the U.S. map. The weirdest thing is that the whole script has been written for an audience of one—Supreme Court swing voter Justice Anthony Kennedy. He isn’t in the courtroom to hear the testimony. But he’s the person whose view ultimately matters.

Alabama’s law is cheerily called the Women’s Health and Safety Act. It’s based on a model bill, written by Washington, D.C., anti-abortion groups and their lawyers, which has passed in whole or part in a slew of states. Over the last 40 years, the states have tried many ways to limit abortion. They’ve imposed waiting periods. Required parental consent for minors. Required ultrasounds. Stopped Medicaid from paying for the procedure. Limited private insurance coverage. Banned particular late-term procedures.

But these tactics mostly seek to discourage women rather than block them entirely. And so, the new abortion restrictions have a different target—clinics. What are known as TRAP laws (for “targeted regulation of abortion providers”) make it prohibitively expensive, or simply impossible, for a clinic to operate. In Alabama, three of five clinics say they will have to close if their doctors are required to get admitting privileges from a local hospital, because no hospital will agree to give this to them. “They did not want a relationship with Planned Parenthood at all,” said one doctor who testified Thursday of the state hospitals, speaking behind a black curtain and under a pseudonym, because of past harassment. “They did not want the political controversies that come with having a relationship with Planned Parenthood.”

There are a few ironies here. Aside from politics, one reason Alabama hospitals refuse to grant admitting privileges is that they only do so for doctors who live within a 30-mile radius. Both of the Alabama abortion providers called to testify travel in from out of state, because if you’re worried enough about backlash to testify behind a curtain, you probably don’t want to move in down the block.

Another reason for the hospital refusals is that the abortion providers send in too few patients to qualify, due to the low rate of complications that demand hospital care. This week’s testimony included the fact that of 2,300 abortions performed in one clinic in Birmingham in 2013, only three patients went to the emergency room. Another fact: The overall rate of abortion patients with complications requiring emergency care is .1 percent. “It’s safer than getting a shot of penicillin,” testified Paul Fine, an obstetrician-gynecologist and medical director of a Planned Parenthood affiliate serving Texas and Louisiana.

Did I mention that the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Medical Association oppose admitting privileges requirements as medically unnecessary?*

When complications do arise, patients can simply go to the emergency room, as they would if they were having a miscarriage and wanted to see a doctor. The admitting-privileges hurdle doesn’t affect their ER access one whit. Defending the law, the Alabama Attorney General’s Office argues that the privileges help women by providing for a “continuum of care.” But the state already has detailed regulations for providers. One rule is particularly relevant: “Every clinic has to have an agreement with a doctor who doesn’t work at the clinic but is a backup doctor, and that person has admitting privileges,” Jennifer Dalven, director of the ACLU Reproductive Freedom Project, told me over the phone.

In a deposition before trial, another ACLU lawyer representing Planned Parenthood asked Alabama State Health Officer Donald Williamson whether the pre-existing state regulations, minus admitting privileges, were adequate. “We were happy with our rules as the governing position on abortion clinics,” he said. Williamson was then asked whether the Department of Public Health had asked to take the admitting privileges requirement out of the state bill before it passed. “Yes,” he answered.

Can we then dispense with the ruse that admitting privileges—or any other component of a TRAP law—are really about protecting women, rather than shutting down clinics? Actually, no, we can’t. The state of Alabama doesn’t want to drop that pose, because it could run into a constitutional roadblock. Here’s the crucial language from the Supreme Court’s 1992 opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which reaffirmed Roe v. Wade: “Unnecessary health regulations that have the purpose or effect of presenting a substantial obstacle to a woman seeking an abortion impose an undue burden on the right.”

Justice Kennedy signed on to Casey, and an undue burden is still supposed to be unconstitutional. So (one more irony) Alabama has to argue in court that this law, passed by abortion opponents who fervently hope it will prevent abortions, won’t prevent abortions. The state even argues that the providers who say they can’t get admitting privileges in fact can. Or that if they can’t, well, the clinics can just hire someone else who will. Right.

Some of the judges who have previously dealt with these laws have seen through them. At an argument about a similar Wisconsin law last December, Appeals Court Judge Richard Posner asked why—if requiring admitting privileges was truly a public health measure—the state targeted abortion clinics, rather than regulating outpatient clinics that do procedures with higher complication rates. “Why did they start with abortion clinics? Because it begins with the letter ‘A’?” Posner asked. In his opinion temporarily blocking Wisconsin’s law, Posner pointed out that the rate of complications requiring hospitalization for colonoscopies is three to six times higher than for abortions. “An issue of equal protection of the laws is lurking in this case,” Posner wrote. “For the state seems indifferent to complications from non-hospital procedures other than surgical abortion.”

In March, though, three judges from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit upheld the Texas law that is like the ones in Alabama and Wisconsin. These judges also heard Paul Fine testify about the rarity of abortion complications that require hospital care. They were also informed that the Rio Grande Valley—a broad swath of southern Texas that is poor, rural, and mostly immigrant—would be left with no abortion clinic if this law went into effect. These judges, who all happen to be women appointed by President George W. Bush, were unmoved. “An increase of travel of less than 150 miles for some women is not an undue burden,” Judge Edith Jones wrote. Since this ruling, the number of clinics in Texas has shrunk from about 50 to 24. And just wait, because another onerous TRAP law, requiring every clinic to be built and equipped like an ambulatory surgical center, is predicted to cut the number of clinics in the entire state to six if it goes into effect in September.

In April, the Fifth Circuit heard a challenge to Mississippi’s version of the admitting-privileges law, which will close the state’s only clinic if it goes into effect. Mississippi’s lawyers reassured the judges that women could travel to neighboring states. Have they looked at a map lately? Along with Alabama and Texas, Louisiana and Oklahoma this month passed bills requiring admitting privileges. The law is expected to close three of five clinics in Louisiana and two of three in Oklahoma. Anecdotally, the Guttmacher Institute says clinics have also closed because of TRAP requirements in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Tennessee, Ohio, and Arizona.

OK, Justice Kennedy, what is the deal? Can it really be that it is not an undue burden to force women to travel hundreds of miles, outside of their state or even their region, to reach an abortion clinic? Even if the health care profession sees the laws that cause clinics to close as medically useless? Because of the expenses of travel, lodging, and often child care, the burden of such a red-state/blue-state divide would be much heavier for poor women. “Whatever the court may do, it’s only the poor women who will suffer,” Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said back in 2010. “When people realize that, maybe they will have a different attitude.” As yet, that hasn’t come to pass. We’ll have to wait for the Supreme Court challenge in which Justice Kennedy reveals his own attitude.

*Correction, May 27, 2014: This article originally called the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists by the wrong name.