Lately, religious liberty has been looking like the freedom that eats everyone else’s for breakfast. In Arizona and other states, fundamentalists said they were acting in the name of religious liberty when trying to pass laws that would allow businesses to refuse to serve people based on theological or moral objection (people who just happened to be gay). And in the Supreme Court challenges to the Obamacare contraception mandate, two companies run by conservative Christians, Hobby Lobby and Conestoga Wood, argue that the government can’t require them to provide health insurance that covers birth control because that would violate the religious beliefs of their businesses. In other cases making their way through the courts, religiously affiliated groups like Notre Dame and the charity Little Sisters of the Poor are objecting to the form their exemption from the contraception mandate takes, because, again, of religion.

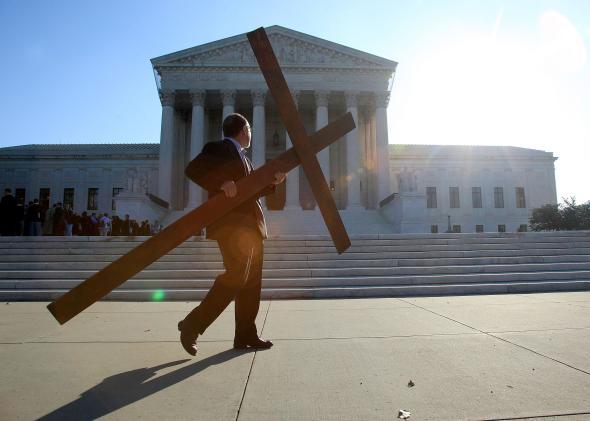

The common thread here is the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which states that when the federal government makes a rule that substantially burdens someone’s free exercise of religion, it has to show a compelling government interest and use the least restrictive means to get where it wants to go. The effort in Arizona, and in other states, is to expand—dramatically—the protections in RFRA. And at the Supreme Court, Hobby Lobby and Conestoga Wood argue that RFRA allows them to refuse to provide birth control coverage to their employees. On these two fronts, religious liberty looks like a shield fundamentalists are throwing up against, well, sexual modernity. They’re not ready to accept same-sex marriage or sex without procreation, and they’re arguing that fundamentalist-owned businesses, as well as individuals and churches, shouldn’t have to.

All of this is giving religious liberty a bad name. In the Hobby Lobby case, groups representing atheists, agnostics, and children are going so far as to argue that RFRA itself is unconstitutional. Their brief, written by Cardozo law professor Marci Hamilton, says this is an “extreme” law that “forces the needs of other believers and nonbelievers to be subservient to the believers invoking RFRA.” But the text of the law isn’t extreme, and up until now the Supreme Court hasn’t interpreted it that way. Instead, the court has gone with a middle-of-the-road reading of RFRA that has promoted respect for religious sensibilities—but stopped short of imposing a significant cost on those other believers and nonbelievers Hamilton’s brief worries about. RFRA strikes a balance, and that’s why liberals as well as conservatives fought for it in the first place.

Let’s start, though, with the big and obvious reason why the new wave of state religious freedom bills goes too far. Businesses that operate as public accommodations, meaning that they’re open to all comers, have to abide by anti-discrimination laws. If you want to refuse to have women or gay people as members, then you should have to operate as a private club open only to your own members. That’s the argument against the Arizona-style laws. (And since Arizona has no law preventing discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, the whole thing is a red herring. In that state, the caterer who doesn’t want to handle a gay wedding doesn’t have to.)

Hobby Lobby’s bid to be protected by RFRA also runs into problems because it’s a business. Congress wrote RFRA to protect “persons” against government regulations that substantially burden freedom of religion without a compelling rationale. While the Supreme Court has previously ruled that “persons” as used in RFRA includes nonprofit organizations like the Catholic Church, it has never said that the law applies to a for-profit business. If the justices wave their wands to turn Hobby Lobby into a person for RFRA, as they did to grant corporations and unions free-speech rights in Citizens United, they will be compounding their Corporations Are People error.

But rooting against Hobby Lobby or anti-gay bills doesn’t have to mean rooting against religious liberty. When Congress passed RFRA, liberals helped take the lead. The law was a disapproving response to a 1990 Supreme Court ruling in the case Employment Division v. Smith, a suit brought by two drug counselors who were fired after taking peyote in a Native American religious ceremony and couldn’t get unemployment benefits because their use of the drug violated state law. Could the state do this, or did their constitutional right to religious freedom mean they should be allowed to use peyote in a religious ceremony without penalty?

The Supreme Court said the answer to that question was no: The employees didn’t have the rights here. Justice Antonin Scalia wrote that since peyote is illegal, and since that law is “neutral” in applying to everyone, the state could impose it. At the time, the ruling read as insensitive to the lack of power religious minorities have relative to the majority. “In law school, I saw Smith as a conservative decision,” Brooklyn law professor Nelson Tebbe remembered when I called him this week. “And when Congress passed RFRA in response, it was about protecting potentially persecuted minorities. But now, in an amazing shift, it’s the most powerful religious organizations in the country that are invoking this law—the Catholic Church and Protestant evangelicals.”

Tebbe is one of the authors of another brief in the Hobby Lobby case—one that I find persuasive. The brief deals with the tension in the Constitution’s dual directive about religion in the First Amendment: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” What happens if your free exercise runs into my right not to have your religious views “established”—in other words, imposed upon me?

The brief by Tebbe and his colleagues argues that this is the collision between Hobby Lobby and its employees. “The Establishment Clause prohibits the government from shifting the costs of accommodating a religion from those who practice it to those who do not,” the professors write. And exempting Hobby Lobby from the contraception mandate “would shift the cost of accommodating Hobby Lobby’s religious exercise to employees who do not share its beliefs.” The brief spells out the cost: Hobby Lobby’s interpretation of religious freedom “would deprive Hobby Lobby’s thousands of female employees and the covered female dependents of all employees of this entitlement. This, in turn, would saddle them with significant burdens ranging from the substantial out-of-pocket expense of purchasing certain contraceptives to the personal and financial costs of unintended pregnancies. The Establishment Clause does not permit this.”

RFRA should be read to observe the limit the Establishment Clause sets, Tebbe and his colleagues argue, and that in itself is a compelling government interest, which is what RFRA requires a federal rule or law to show. A wave of relief hit me when I read this. Even if the Supreme Court screws up and says that Hobby Lobby is a “person,” the company should still have to provide contraception coverage to the women who work for it. That’s because the government has a compelling reason for requiring birth control as part of comprehensive preventive care for women, as I’ve explained before. Preventing unintended pregnancy is a benefit to women’s health. And Hobby Lobby also should have to provide contraception coverage because its religious rights don’t trump the rights of its employees.

RFRA calls for a balancing act. And in most of the previous Supreme Court cases in which the court has recognized an exemption from a law for a religious group, it’s been in a circumstance where there’s little or no cost to other people. If Native Americans want to take peyote as a form of worship, or another group, in another Supreme Court case, wanted to drink hallucinogenic tea, they can do it without burdening the rest of us. Ditto for the Amish family that didn’t want to send their children to regular school, as state law required, and won at the Supreme Court back in 1972, before Smith.

For businesses, when religious freedom comes at a cost to employees or customers, it has to give. That’s the best way to interpret RFRA, and it’s also the best fit for the American tradition of tolerance. This is a country of live and let live. That’s how businesses as well as the government have to function. Hobby Lobby’s owners can object to forms of birth control personally while respecting the rights of their employees to receive it as a benefit. And if a state has the sense to outlaw discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, then the owners of companies that are in the wedding business can steer clear of gay marriage on their own time, but when their doors are open to the public, then they serve whoever walks in. That’s what religious liberty has to mean in the end. Now let’s get there.