When a federal judge decided last week that the city of Detroit could go bankrupt, city workers feared the loss of their pension plans and creditors worried about getting paid back. One person, though, stands to take a huge and gallingly unjust hit.

Dwayne Provience spent nearly a decade in prison for a murder he didn’t commit. When he got out and cleared his name three years ago, he filed a civil lawsuit against the city. A settlement panel proposed a payment of $5 million. The city either had to agree to pay, or go to trial—risking exposure of police misconduct, and a potentially larger damages award.

It seemed like justice, finally, for Provience. But then came Detroit’s bankruptcy. His lawsuit is now in limbo—which means that for the foreseeable future, he will get nothing. Through no fault of his own, he has been shortchanged again.

Fourteen years ago, when Provience was 26, he had a house and a job. He was raising two young children and had a loving, close-knit family. Then he was named a suspect in the murder of a local drug dealer named Rene Hunter.

Hunter was shot and killed in broad daylight from a car as he walked near a busy intersection in northwest Detroit in March 2000. Seven witnesses to the shooting, including an off-duty police officer, described the shooter’s car as a four-door gray Chevy Caprice Classic. None of those witnesses said they saw the shooters themselves, but neighborhood police officers worked their sources and soon had a good idea of who they were. Police progress notes made in May 2000 suggest they suspected Sorrell and Antrimone Mosley, drug bosses who were upset with Hunter because they thought he had stolen a shipment of their drugs. The Mosleys owned a gray Chevy Caprice, and neighborhood sources told police that the Mosleys had just had an altercation with Hunter and pursued him to the intersection where he was shot.

Still, no arrests were made until June. That’s when the police picked up Larry Wiley, a homeless crack addict, for breaking and entering. Wiley was a repeat offender facing prison time again. He told the police that he had crucial information about the Hunter killing: He was there, on his bike, and he saw it all go down. The shooter was a guy he knew from the neighborhood: Dwayne Provience.

Wiley said Provience fired out of a two-door Buick Regal driven by his brother, De-Al. That didn’t match any other witnesses’ description of the shooter’s car. It did not add up either with what police suspected about the Mosleys’ involvement. Still, the police arrested the Provience brothers. Wiley agreed to testify against them, and the charges against him were dropped.

De-Al was acquitted. But Dwayne’s lawyer called none of the seven witnesses from the scene of the crime in his defense. He was convicted and sentenced to 32 to 62 years in prison. His lawyer later had his license revoked for a pattern of similar failures.

I work for the Michigan Innocence Clinic, which took Provience’s case in early 2009. After a lot of digging, our students found Wiley living under a highway overpass. In a videotaped statement, he admitted to lying at Provience’s trial in order to stay out of prison himself.

Our students kept knocking on doors and looking for more information. We learned that there had been another killing in the neighborhood weeks after Hunter’s death. Records found in that case file revealed, stunningly, that the police should have known that Provience was innocent even as the state was prosecuting him.

Weeks after Rene Hunter’s death, a friend of his, Courtney Irving, was killed. A man named Eric Woods was convicted for that murder. At Woods’ trial, prosecutors argued that the Mosley brothers recruited Woods to kill Irving because Irving was about to tell the police that the Mosleys had themselves killed Hunter. Though all of this was known to law enforcement, the same prosecutor’s office still tried and convicted Dwayne Provience for that same murder.

When we spoke to the neighborhood police officers who had initially investigated both homicides and knew all about the Mosleys, they were shocked to hear about Provience’s conviction. “How on Earth did that happen?” one of them asked us. Another officer would go on to reveal that he had told the detectives pursuing Provience that Wiley was lying and the Mosleys had killed Hunter. None of that information was ever disclosed to the defense at trial.

When we presented our new evidence of Provience’s innocence in court, the judge threw out the conviction, and granted a new trial. The prosecution stalled for months, indignantly expressing intent to retry Provience, before finally agreeing to drop charges in March 2010. Nearly 10 years after his initial arrest, Provience was finally a free man.

In some states he would have been automatically entitled to compensation for the years he spent in prison because of his wrongful conviction. But Michigan has no such law. Instead, Provience sued for damages, arguing that the police officer in charge of his case had suppressed evidence favorable to the defense—including police progress notes and witness statements implicating the Mosleys—contributing to his wrongful conviction.

When the settlement panel convened by the court proposed the $5 million payment, the city of Detroit tried to have the lawsuit thrown out. Last July a federal appeals court said the suit was valid and could proceed to trial. That was an unlikely step for the city to take. “This case was inches from being settled for $5 million,” says Wolfgang Mueller, Provience’s lawyer.

But the bankruptcy has derailed that. Now Provience waits his turn in a long line of unsecured creditors, to eventually settle his claim for pennies on the dollar.

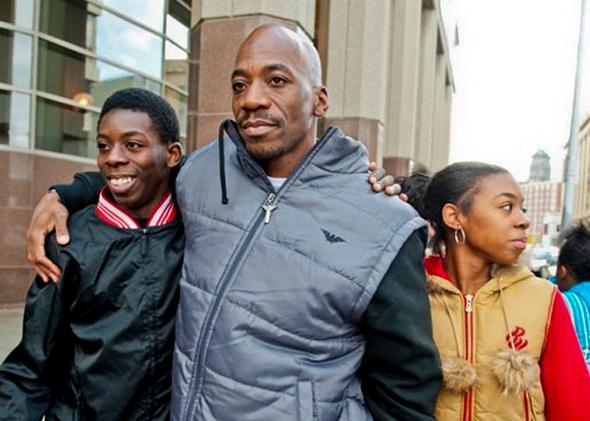

Provience works as a personal trainer and a rehabilitation specialist. He’s gotten back together with the woman he was dating before his arrest, and they have a 2-year-old son. His two older children, a son and a daughter, who were just 5 and 6 years old when he was sent to prison, are now in college. Provience plans to enroll in college himself in January. He wants to be a physical therapist. The lawsuit money would have helped him achieve this goal and pay his children’s tuition. Despite the setback and uncertainty, he’s still forging ahead.

“I want to open up my own physical therapy place and be my own boss,” he says, “I’ve had too much of people telling me what to do.” It’s hard to disagree with that.