The court papers don’t tell us all that much about what happened between the couple described only as “J.B.” and “H.B.” We can assume there once was love and then, at some point, there wasn’t. Their parting, we’re told, was amicable.

The problem is that J.B. and H.B. are both men. The other problem is that they live in Texas. The two were married in Massachusetts in 2006, where same-sex marriage has been legal since 2004. They later moved to Texas, and now want to get divorced. Texas, however, won’t let them. And they cannot get divorced in Massachusetts either, because that state—like all states—has a residency requirement for divorce.

Thus, unless they uproot their current lives in Texas and move to a state that will grant same-sex divorces, J.B. and H.B. are locked into their marriage. They are in perfect legal limbo. And they are in it together until death—or the state of Texas—do them part. Being trapped in a marriage one wishes to leave is a situation one court (referring to an opposite-sex marriage) once described as “cruel and unusual punishment”—placing the spouses “in a prison from which there was no parole.”

J.B. sought a divorce from H.B. in Texas in 2009, and a family court judge granted the petition, holding that Texas’ Proposition 2, which prohibited the court from recognizing a same-sex marriage, violated the due-process and equal-protection guarantees of the Constitution. But in 2010 a three-judge panel of Texas’ appeals court reversed the family court ruling, declaring that because same-sex marriages or civil unions are barred by a 2005 voter-approved amendment to the Texas Constitution and Family Code, Texas courts have no jurisdiction to grant same-sex divorces. Divorcing a same-sex couple would require the state to recognize that they were married in the first place. And this, the state says, it cannot do.

On Nov. 5 the Supreme Court of Texas will hear arguments regarding whether the men’s constitutional rights are violated by not granting them a divorce. J.B. and H.B.’s case is actually one of two same-sex divorce cases now pending before the Texas Supreme Court. In a second case, the same-sex divorce was granted to a lesbian couple after a state appeals court determined that the state of Texas intervened too late.

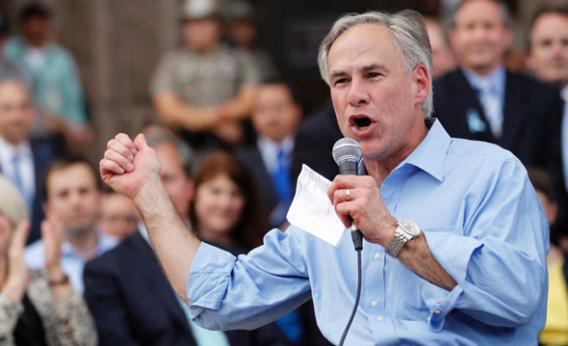

These cases have placed Texas’ highest state officials in the ironic—one could even argue rather romantic—position of fighting to keep two gay couples married to one another. Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott intervened in the J.B and H.B. divorce case, taking the position that “because the Constitution and laws of the state of Texas define marriage as the union of one man and one woman, the court correctly ruled that Texas courts do not have authority to grant a same-sex divorce.” Any other ruling, he said in a statement, would allow other states to impose their values on Texas.

This is not just a Texas problem. More than 30 states ban same-sex marriage by constitutional amendment or statute. While Georgia, for instance, explicitly bars same-sex divorce, Texas and most of the others prohibit only gay marriage. So J.B. and H.B. may well reflect the new frontier in the same-sex marriage wars: What to do about states declining to grant divorces to legally married couples? According to the brief filed by J.B., right now in the U.S., “over 28 percent of the U.S. population lives in a jurisdiction where same-sex marriage is permitted.” He adds that “Texas is one of the fastest growing states — attracting thousands of migrants each year, including couples from those states that permit same-sex marriage.”

Texas, meanwhile, takes the position that being forced to recognize same-sex divorce is no different from being forced to accept gay marriage. In an amicus brief filed before the state Supreme Court on Texas’ side of the case, a Republican state legislator contends that “this lawsuit demonstrates that opponents of traditional marriage want to exclude the people of Texas from the legislative process — and then they want to exclude the legal representative of the people of Texas, the Attorney General of Texas, from the judicial process.”

For his part, J.B. contends that no one is asking Texas to issue any same-sex couple a marriage license or to afford them any of the benefits of being married in Texas. Marriage and divorce are different beasts, he claims. And nothing in the text or intention of the Texas ban on same-sex marriages is violated by allowing them to divorce. Daniel Williams of Equality Texas, the statewide LGBT advocacy group, says that “granting a divorce is not creating a marriage. In fact the law is very clear: the ability to get a divorce is a benefit of living in Texas, not a benefit of marriage.”

Instead, those in support of the men urge, Texas should be eager to seal the deal on the end of this relationship. “The divorce of married same-sex couples furthers the purported public policy of Texas that same-sex couples should not live as ‘married’ in the State,” the ACLU of Texas and Lambda Legal argued in an amicus brief filed in the state Supreme Court. It would be “astonishing” for the court to hold otherwise.

Seeking a legal decree of divorce is far from mere semantics or hyperbolic trouble-making by gay-rights activists. After the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision this past June in United States v. Windsor, J.B. and H.B. are in a marriage recognized by many states and the federal government. As long as they remain married, they are accruing rights and responsibilities to each other such as shared property and debt. Furthermore, the Internal Revenue Service recently declared it would recognize all marriages from places (like Massachusetts) that allow same-sex marriage regardless of where the couple currently lives. This means J.B. and H.B. must continue to file their federal taxes as “married.”

But the constitutional rights at issue are also crucial. These men are, after all, seeking equal treatment under law and access to their court system, which the Supreme Court has declared to be a fundamental right. Without access to the courts, they are unable to divide property and debt, settle child custody matters, clarify rights to Social Security, retirement, and health benefits, or resolve other vital interests. In addition to these practical considerations, there is an emotional interest at stake: A divorce decree brings finality and repose. It provides an opportunity to move on, because without a divorce these men are prohibited from remarrying. As Mary Patricia Byrn and Morgan Holcomb wrote last year in the University of Miami Law Review, denying same-sex couples a divorce implicates the “due process trinity” of the right of access to courts; the right to divorce; and the right to remarry.

Texas counters that J.B. and H.B. are far from trapped in the legal oblivion just described. They have a perfectly valid option: They can ask that their marriage be declared “void.” In other words, the state is willing to declare that their marriage never existed in the first place. Thus while the men wish to check the “divorced” box, the state is offering a chance to check the “never married” box instead. No harm, no foul.

But this is a transparently flawed solution. The fact is that these two men were married. Texas is trying to retroactively declare that a marriage deemed valid in Massachusetts was never real. And while a state’s ability to be hostile and dismissive to the desires of same-sex couples is still under debate throughout this country, a state’s inability to be hostile and dismissive to the legal declarations of other states is a pretty settled matter.

Simply voiding the marriage creates its own problems. The spouses might have had children or accumulated joint property and debt. Extinguishing the marriage from its outset would flush those legal rights down the drain. Children who were born or adopted to such marriages, for example, could find their legal rights vis-à-vis their parents brought into question. A spouse who raised those children while the other worked or went to school, meanwhile, might have no claim to alimony. As one court has put it, retroactively invalidating marriages would “disrupt thousands of actions taken … by same-sex couples, their employers, their creditors, and many others, throwing property rights into disarray, destroying the legal interests and expectations of … couples and their families, and potentially undermining the ability of citizens to plan their lives.”

But even that isn’t the most worrisome problem. Simply voiding a years-long, state-sanctioned marriage forces the couple to pretend that something as significant in their lives as their legal union never occurred. The state’s “attempt to ‘erase’ their lived history,” the ACLU and Lambda Legal brief argues, “is demeaning and demonstrates nothing more than a desire to express public disapproval of their constitutionally-protected intimate relationship.”

The U.S. Supreme Court, at least for now, has left the issue of whether to allow same-sex marriage to the states. That, however, is not the same thing as allowing Texas to pretend that the world outside its borders thinks as it does. A difference of opinion about same-sex marriage is one thing, but a willful embrace of an alternative reality—particularly by papering over the basic facts of individuals’ lives—is quite another. States can’t rewrite the stories of their citizens’ lives into works of fiction.

It is a sad fact of life that marriages—both gay and straight—sometimes end. It is a matter of dignity that extends beyond the current politics of same-sex marriage, to allow everyone the right to move on when they do.