This fall, the Supreme Court will hear a big case about church and state, Greece v. Galloway. Greece, a town in upstate New York, routinely opens its city council meetings with prayers from local clergy. The 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals held that practice unconstitutional, finding the prayers had been overwhelmingly Christian. Because the facts are somewhat murky and the law murkier still, few people initially noticed the case. But last May, the Supreme Court agreed to decide it. And now suddenly everything is up for grabs.

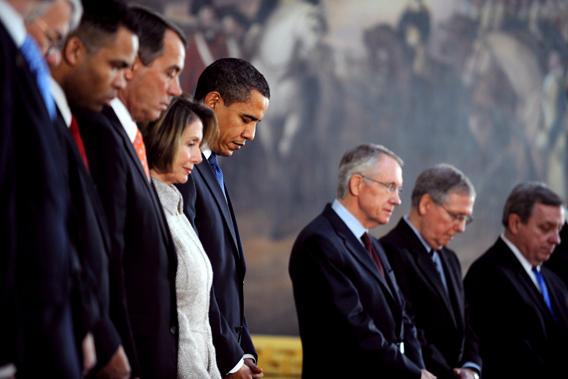

Greece v. Galloway is still a case about legislative prayer. But at least one side is using the appeal as a vehicle to have the court totally revamp its approach to the Establishment Clause. The court may just bite. And in a truly remarkable turn this week, the Obama Justice Department just came into the case—on the town of Greece’s side! Contrary to the positions of most appeals courts (and even some reliably conservative judges), and contrary to the language of earlier Supreme Court opinions, the solicitor general now takes the position that Greece’s practice is perfectly constitutional and the presence or number of Christian references doesn’t matter.

To understand Greece, we must begin with an earlier case—the Supreme Court’s 1983 decision in Marsh v. Chambers. Marsh involved a First Amendment challenge to Nebraska’s practice of having a permanent chaplain open legislative sessions with a prayer. The challenge was not far-fetched: The court had interpreted the Establishment Clause to prohibit government from favoring religion for decades, and legislative chaplaincies seemed a clear violation of that principle. Yet, in a 6–3 decision, the Supreme Court upheld Nebraska’s practice, making a small but important exception to its stated mandate of religious neutrality. In justifying that departure, the court stressed the long history of legislative prayer in this country. The First Congress approved the Establishment Clause, the court said, but it also hired chaplains. Clearly, then, legislative prayer did not violate the Establishment Clause.

Yet, while Marsh accepted legislative prayer, it implied there would be limits. One part of the opinion provided that legislative prayer could not be “exploited to proselytize or advance any one, or to disparage any other, faith or belief.” In another, the court noted approvingly that Nebraska’s chaplain had dropped Christian references from his prayers following a complaint. So Marsh seemed to impose a limit on prayers—they could not be too denominational—but the court never explained precisely where the line should be drawn.

Greece v. Galloway picks up where Marsh v. Chambers left off. The town of Greece began inviting local clergy to offer prayers back in 1999. Until 2007, all the prayer-givers were Christian and their prayers tended to use identifiably Christian language, with frequent devotional references to Jesus Christ and frequent instructions for the audience to join in. After complaints, the prayer-givers temporarily got more diverse—a Wiccan priestess gave a prayer, as did the head of a Bah’ai congregation and a Jewish layperson. The town even said that atheists and agnostics could sign up to give invocations (though it did not publicize that fact). Yet the bulk of the prayers remained identifiably Christian. And since 2009, for reasons not entirely clear, all of the prayer-givers have again been Christian clergy.

The plaintiffs’ argument is simple. The town arranged to have these prayers, chose these prayer-givers, gave them the podium, and required everyone else to be quiet and listen respectfully if they wanted to attend a legislative session or do business with the legislature. The prayer-givers are speaking for the town, and these are the town’s prayers. The town can no more disclaim them than it could disclaim the prayers of a public school teacher who prays over the public address system. So when these prayers end up all being identifiably Christian, the town is favoring Christianity.

The Supreme Court is deeply divided on whether the government can endorse religion generally or whether it must remain strictly neutral—witness the recent fights over “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance or the internal confusion over the constitutionality of Ten Commandments displays. But there is much more widespread support, both on and off the court, for the proposition that the government can’t favor one particular religion over others. “I have always believed, and all my opinions are consistent with the view,” Justice Scalia once wrote, “that the Establishment Clause prohibits the favoring of one religion over others.” Marsh itself is grounded in this idea; Marsh speaks of legislative prayer as a “tolerable acknowledgment of beliefs widely held among the people of this country.” But that all falls apart if speakers pray in ways that alienate and offend their audiences.

We are still waiting for the plaintiffs to file their brief, but the defendant’s opening brief advances several theories, without seeming to recognize that they are irreconcilable. One part of the brief, for example, defends Greece’s actions by arguing that none of the prayers were proselytizing or disparaging. (It is not clear that this is factually true, and it plays a little fast and loose with the actual language from Marsh—remember Marsh spoke of legislative prayers that “proselytize or advance any one, or disparage any other, faith or belief.”) But the town’s brief also says it cannot censor prayers at all because doing so would violate the Free Speech Clause. Even odder is the brief’s general conception of the Establishment Clause, which the town says is only violated by “laws that tax citizens to support a particular church or compel adherence to particular tenets or beliefs.” That is a sentence from bizarro-world. Were it true, the government could force us all to sit through other peoples’ church services as long as we were not required to affirm what was said.

But the really big surprise came this week when the Obama administration filed its own brief on the defendant’s behalf. The administration did not need to say anything at all about this case. But that it would file on the defendant’s side was shocking, especially given that the vast majority of lower court decisions side against Greece. To be sure, the solicitor general’s brief strikes a more moderate tone than the defendant’s. In fact, it sides with the plaintiffs on much of the law—agreeing that prayers cannot be overwhelmingly Christian without unconstitutionally affiliating the government with Christianity. But then for some reason, not really articulated in the brief, the solicitor general concludes that the situation in Greece is not quite bad enough to violate the Constitution.

It’s not clear the plaintiffs will have an easy time in court. Greece claims it is willing to accept anyone (religious or not) who wants to offer an invocation, and nothing obviously disproves that claim. The 2nd Circuit ruled that the plaintiffs have abandoned the argument that Greece discriminated against prayer-givers of particular denominations, which has been a real problem in other cases. (There is a 4th Circuit case involving a Wiccan who received a letter saying she could not pray because she was a Wiccan, and an 11th Circuit case about a town that deliberately excluded Mormon, Jewish, and Islamic clergy from participating.) To the defendant, the plaintiffs’ claim here is simply that there is just too much Christian stuff. And that, the defendant says, amounts to a thoroughly awful kind of religious censorship.

Both sides have valid concerns. In an important sense, legislative prayer ends up being a zero-sum game for religious liberty. Listeners deserve to be protected from their government making religious statements with which they disagree. But protecting them requires speakers to change the ways they pray. It’s a classic Catch-22, but it captures a very obvious point: We live in a world where people have different religious beliefs. Some folks, of course, do not pray. But those who do pray in different ways; they pray to Gods that they do not see as the same God. In that world, there is just no way for the government to pray in a way that satisfies everyone. This has always been the central problem with the government practicing religion: Whose religion will it practice?

Thirty years ago, the court spoke of legislative prayer as “simply a tolerable acknowledgment of beliefs widely held among the people of this country.” But each time a local government decides to allow legislative prayer, it has to make religious choices, choices that inevitably that cause conflict. Who gets to pray? You could try to let everyone pray. But some speakers will abuse the opportunity. There’s also an incredible temptation to play favorites. These are elected bodies; letting the Wiccan pray comes with political consequences. And what will you do about the content of peoples’ prayers? Say nothing, make suggestions, issue requirements, require drafts of prayers in advance? And whatever the rules are, how will you enforce them? What if a prayer-giver suddenly goes off-script, and begins praying about how abortion is murder or about how gays and lesbians deserve to be ordained? (Those are real examples.) Do you cut off the microphone? Try and sanction them afterward? And what will you do if they get interrupted? The Senate once invited a Hindu guest chaplain to offer prayers, and he got interrupted by protestors in the balcony. Those protestors received prison terms.

In the end, because these choices are made by politicians, these controversies spill out into politics. Most law professors and judges live in big cities, but entire local elections in small towns have been decided on legislative prayer issues. Religious campaigning becomes inevitable. One small town in California recently considered banning denominational prayers.* In response, a citizens’ group purchased billboard space on nearby highways and threatened to display each council member’s vote under one of two columns—“For Jesus” or “Against Jesus.” In a recent 9th Circuit case, a city held a referendum on whether prayers to Jesus Christ should be allowed. Twelve thousand votes were cast—76 percent in favor, 24 percent opposed.

This is disturbing, but not surprising. This is what happens when the government takes positions on religious issues. People want the government to adopt their religious views. They will campaign for their religious positions; they will vote for them; they will lobby for them. If we agree that there is something troubling here, what we are really agreeing on is the idea that the government should not take religious positions. Marsh v. Chambers moved us away from that idea. Greece v. Galloway will almost surely not overrule Marsh. But it would be a loss if Greece takes us even further away.

Correction, Aug. 15, 2013: This article originally misstated that a small town in California considered banning nondenominational prayers. They considered banning denominational prayers. (Return to the corrected sentence.)