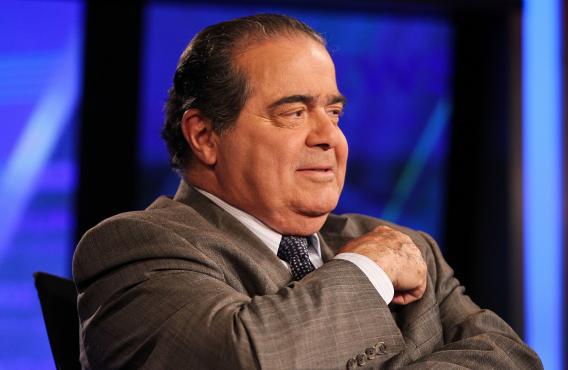

In a speech last week titled “Mullahs of the West: Judges as Moral Arbiters,” Justice Antonin Scalia told the North Carolina Bar Association that the court has no place acting as a “judge moralist” in issues better left to the people. Since judges aren’t qualified—or constitutionally authorized—to set moral standards, he argued, the people should decide what’s morally acceptable.

But does Scalia, whose quarter-century on the bench has marked him as the court’s moral scold for his finger-wagging views on social issues, have a coherent understanding of what it means to say something is or isn’t moral, and of morality’s proper role in the law?

Scalia would have you believe it’s liberal, pro-gay sympathizers who are imposing their own brand of moral laxity on the nation, and unconstitutionally using the courts to do it. His angry dissent in the 2003 Lawrence v. Texas case ending sodomy bans—decided 10 years ago this week—blasted the court for embracing “a law-profession culture that has largely signed on to the so-called homosexual agenda [which is] directed at eliminating the moral opprobrium that has traditionally attached to homosexual conduct.”

Ever since, Scalia has been railing against the loss of “moral opprobrium” as a legitimate basis for passing laws. Scalia implies that whatever the people feel should rule the day, constitutional rights be damned. “Countless judicial decisions and legislative enactments,” he wrote, “have relied on the ancient proposition that a governing majority’s belief that certain sexual behavior is ‘immoral and unacceptable’ constitutes a rational basis for regulation.” A long string of state laws, he argued, are “sustainable only in light of” the court’s “validation of laws based on moral choices,” including bans on incest, prostitution, masturbation, adultery, fornication, bestiality, public indecency and selling sex toys.

Yet as Sandra Day O’Connor pointed out in her concurring opinion in Lawrence, that’s not actually true. At least when you’re singling out a group for separate treatment. “We have never held that moral disapproval, without any other asserted state interest, is a sufficient rationale under the Equal Protection Clause to justify a law that discriminates among groups of persons.”

Scalia may wish that moral disapproval alone were a legitimate basis to discriminate, but if you read his Lawrence dissent closely, you’ll find evidence that he knows he’s lost that battle: The giveaway is that he nearly always pairs his references to morality with some other asserted state interest. He defends the people’s right to legislate their belief that some forms of sex are “immoral and unacceptable,” to oppose, by law, “a lifestyle that they believe to be immoral and destructive,” and to pass public indecency statutes to protect “order and morality.”

The American legal system, while making some room for moral complaint in law, has nearly always paired it with some more concrete form of harm. According to the legal scholar Diane Mazur, the Supreme Court has, for most of its history, combined reference to morality with other actual harms such as threats to order, health, safety and welfare. It decided cases on the importation of slaves based on the “health and morals” of the people; it decided whether to permit a civil rights march based on its impact on the town’s “safety, health, decency, good order, morals or convenience”; and it decided cases about nude dancing based on a state’s interest in “protecting societal order and morality.”

In each case, “morality” seems an afterthought—something that legislators or judges throw into the mix to make a point, but never the real basis of law. If what’s really at issue are acts that threaten safety, health, and order, why do people like Scalia keep insisting that mere moral disapproval, rather than preventing harm, should be a constitutionally legitimate basis to limit people’s rights?

The entire anti-gay movement has gotten this memo. Which is why arguments that gay people are sick, disgusting and all-around morally bad have yielded, since the 1990s, to arguments alleging that gays threaten to cause concrete harm to American families and institutions. Of course, many social conservatives, often animated by their religious traditions, still believe homosexuality is immoral. And this view occasionally still appears in arguments against gay marriage, as when the proponents of Prop 8 claimed that the initiative advances “important societal interests” like accommodating the rights of those who “support the traditional definition of marriage on religious or moral grounds.”

But these days anti-gay advocates mostly stick to claims of harm, even bending over backward to insist they don’t view homosexuality as a moral issue. Societies have historically restricted marriage to opposite-sex pairs, argued Prop 8’s defenders, “not because individuals in such relationships are virtuous or morally praiseworthy, but because of the unique potential such relationships have either to harm, or to further, society’s vital interest in responsible procreation and childrearing.”

If you’re obsessed with morality, like Scalia, that approach must be irritating indeed. Scalia seems to reduce morality to feelings and tastes alone. He wants judges to get out of the way and respect that “people may feel that their disapprobation of homosexual conduct is strong enough” to pass laws against them. For him, it was the very “impossibility of distinguishing homosexuality from other traditional ‘morals’ offenses” that allowed the court to ban sodomy prior to Lawrence.

But homosexuality is distinguishable from other morals “offenses.” Assisted suicide, incest, adultery, pornography—all these arguably cause some form of harm to living creatures, while two women loving each other just doesn’t. We can argue this point and debate the subtleties of that harm—Is a fetus a full human with capacity for pain? Does pornography necessarily degrade women? Indeed the healthy—and genuinely moral—society is the one that does debate these points instead of lumping together whatever scrunches up our noses into the amorphous category of a moral wrong.

What we should no longer be able to get away with in the 21st century is calling something immoral just because we don’t like it. Genuine moral judgment is not reducible to whatever people feel, what they like or don’t like. (Isn’t that what lax liberals are alleged to believe?) Morality is not just whatever views a majority has long held, and it’s not simply what you learned on your mother’s knee or whatever it says in your faith’s scripture. Moral belief is a grounded judgment about what harms or helps living things. Yet somehow, homosexuality’s become just about the only thing left that people get to call immoral without every explaining why.

If equal treatment of gay people harms society, that alleged harm should be debated. But trying to defend discrimination by giving free rein to some people’s moral disapproval of homosexuality is a losing battle, and a shockingly sloppy mode of thinking about what “morality” actually means. Morality actually has a rational basis; moralists, not so much.