The Supreme Court’s ruling in Fisher v. University of Texas won’t end race-based affirmative action. The court made it harder for schools to defend their policies but not impossible. Justice Anthony Kennedy said for the majority, about any court faced with a challenge to a university’s affirmative-action policy, “The reviewing court must ultimately be satisfied that no workable race-neutral alternatives would produce the educational benefits of diversity.”

Still, this decision could—and should—lead to a smarter kind of affirmative action that is mostly based on class rather than race. Ten states have banned race-based affirmative action, usually by voter initiative. After the bans passed, an initial dip in minority enrollment often followed. But then in most of these states, schools created new programs to promote racial and ethnic diversity indirectly by giving an admissions preference to low-income students, boosting financial aid, and reducing reliance on test scores. I show this in a report I wrote with Halley Potter, A Better Affirmative Action: State Universities that Created Alternatives to Racial Preferences (PDF).

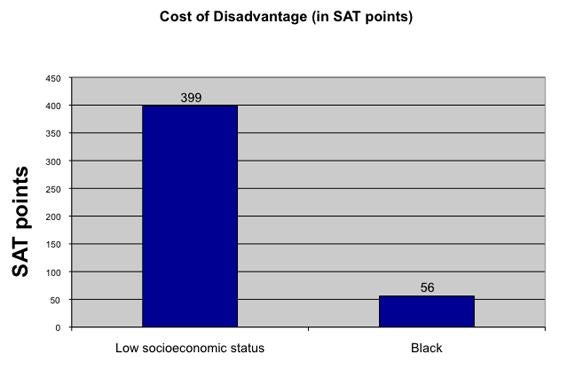

The new affirmative action, based primarily on economic disadvantage, better addresses the glaring inequities students face. As you can see from the chart below, a student who is socioeconomically disadvantaged, in a variety of ways, scores on average 399 points lower on the SAT than a wealthy student. By contrast, the average SAT difference between African-American and white students of the same socioeconomic status is only 56 points.* In other words, the SAT class gap is seven times as large as the SAT race gap.

Source: Anthony P. Carnevale and Jeff Strohl, “How Increasing College Access Is Increasing Inequality, and What to Do about It,” in Rewarding Strivers: Helping Low-Income Students Succeed in College, Richard D. Kahlenberg, ed., (New York: Century Foundation Press, 2010), 170, Table 3.7.

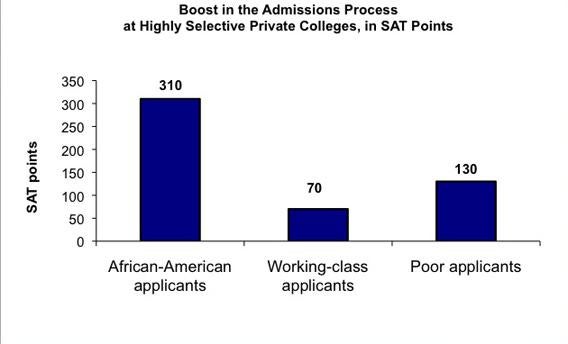

If universities wanted to be truly meritocratic in admissions, they would weight socioeconomic status heavily and race lightly. In fact, research shows that selective universities do the opposite.

Source: Thomas J. Espenshade and Alexandria Walton Radford, No Longer Separate, Not Yet Equal (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009), 92, Table 3.5.

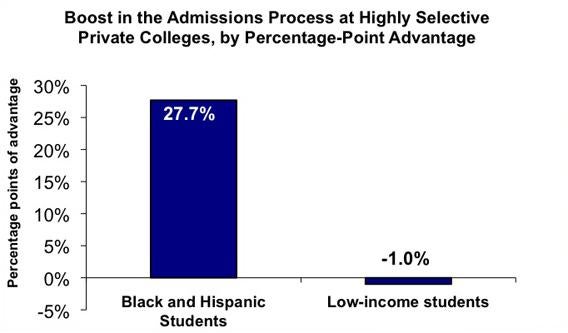

Currently, selective schools boost the chances of admission of black and Hispanic students by 28 percentage points. That is, if a white candidate has a 30 percent chance of being admitted based on her record, an African-American or Latino student with the same record has a 58 percent chance. By contrast, low-income students receive no boost whatsoever.

Note: Figures refer to 1995 applicant pool. Adjusted admissions advantage for Bottom income quartile is calculated relative to middle quartiles. Source: William G. Bowen, Martin A. Kurzweil, and Eugene M. Tobin, Equity and Excellence in American Higher Education (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2005), 105, Table 5.1.

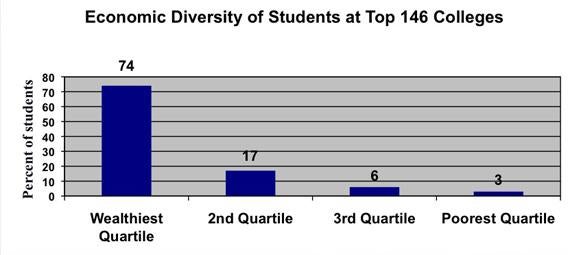

Colleges and universities say they care about economic diversity among students. But 74 percent of students at the most selective 146 schools come from the top socioeconomic quarter of the population, while just 3 percent come from the poorest quarter. Put differently, you are 25 times as likely to run into a rich kid as a poor kid on these campuses.

Source: Anthony P. Carnevale and Stephen J. Rose, “Socioeconomic Status, Race/Ethnicity and Selective College Admissions,” in Richard D. Kahlenberg (ed), America’s Untapped Resource: Low Income Students in Higher Education (The Century Foundation, 2004), p. 106, Table 3.1.

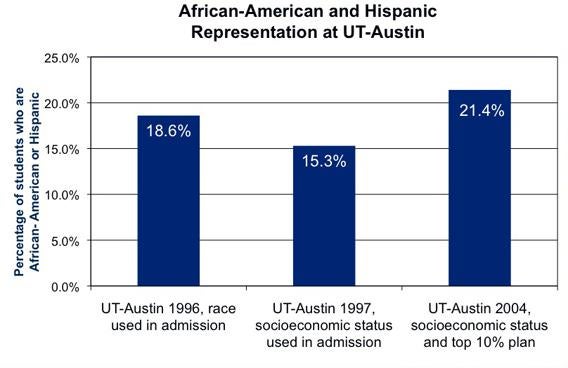

What happens to racial diversity when colleges stop using racial preferences in admissions? The numbers of minority students don’t necessarily drop. After the University of Texas at Austin was barred from considering race by a 1996 court decision, officials started factoring in socioeconomic status. Then the university began admitting students who graduate in the top 10 percent of their high school class. By 2004, these race-neutral plans, coupled with growing diversity statewide, produced more racial and ethnic diversity at UT–Austin than had been achieved in 1996 using race.

Source: Brief for Petitioner in Abigail Noel Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, et al., http://www.projectonfairrepresentation.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/08/Brief-for-Petitioner-Fisher-v-Univ-of-Texas.pdf

*Correction, June 28, 2013: Because of an editing editor, the sentence originally specified low-income students. In fact the students represented in the chart are socioeconomically disadvantaged in a variety of ways. (Return.)

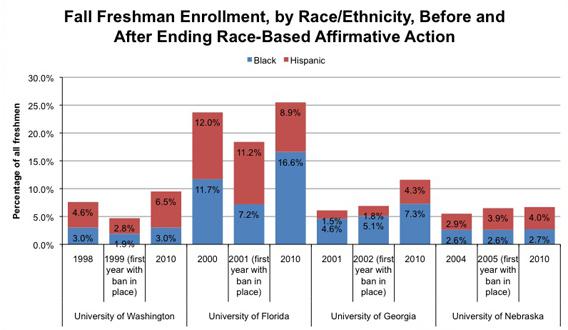

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/

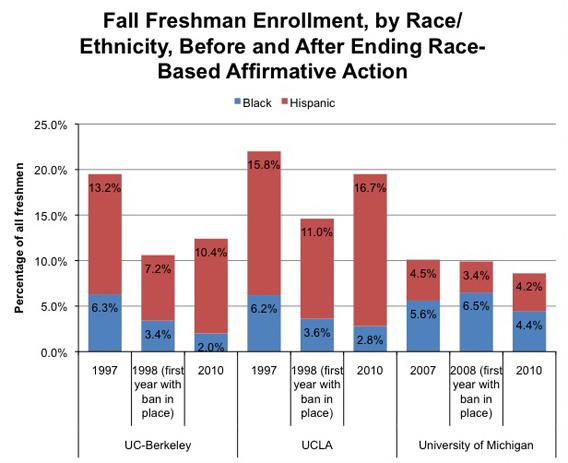

Among the 10 leading public universities in states that banned racial preferences, three did not fully restore black and Latino representation using economic affirmative action and other race-neutral means. Those schools are UC–Berkeley, UCLA, and the University of Michigan. They are the three most selective schools in the study Halley Potter and I did, and the most likely to draw from a national pool of applicants. That’s important because Berkeley, UCLA, and Michigan were competing for minority students with other universities that could continue to use racial preferences in admission. Given that uneven playing field, it’s not surprising that these three universities have had difficulty in recruitment.

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/

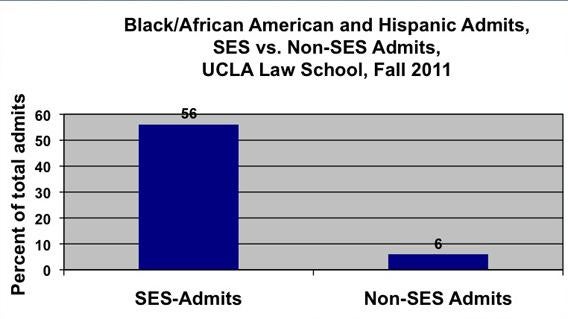

Some studies find that income-based affirmative action won’t produce much racial diversity. That’s true in part because, on average, compared with whites of the same income level, black and Latino students face extra obstacles—they are more likely to live in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty, and to have less family wealth. UCLA Law School developed a definition of socioeconomic disadvantage that includes family wealth and neighborhood poverty, as well as income. Using those measures, the school admitted far more black and Latino students than it did using the regular admissions standards that didn’t include these factors.

Source: Karman Hsu, director of admissions, UCLA Law School, email to Halley Potter on September 4, 2012.

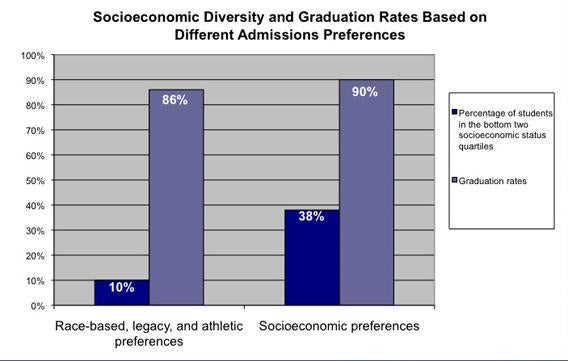

If schools admit more low-income students, will graduation rates drop (because of poor preparation in K–12)? A simulation of admissions at the most selective 146 universities shows that graduation rates would slightly rise if the proportion of students from the less wealthy half of the population rose increased from 10 percent to 38 percent, using admissions standards based on merit plus class-based affirmative action, and compared with current admissions policies that take into account merit, race, athletic status, and legacy status.

Source: Anthony P. Carnevale and Stephen J. Rose, “Socioeconomic Status, Race/Ethnicity, and Selective College Admissions,” in America’s Untapped Resource: Low-Income Students in Higher Education, Richard D. Kahlenberg, ed. (New York: Century Foundation Press, 2004), 142, 149.

The Fisher decision could be something of a setback for upper-middle-class minority students, but it should be a boon for low-income students of all races as universities develop a new, and better, form of affirmative action based on class.