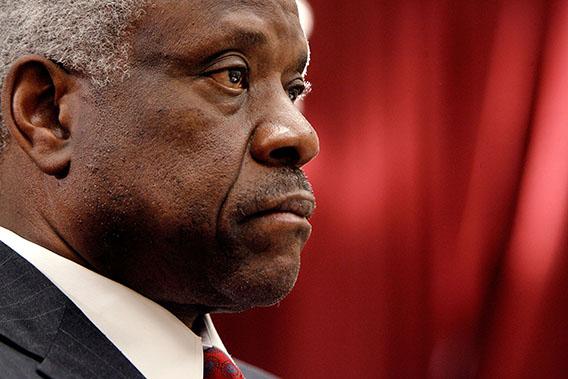

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas is frequently accused of being a partisan hack, a conservative lackey serving only the interests of the Republican Party. His votes are often portrayed as products of political ideology rather than constitutional philosophy, a practice he only encourages with his forays into political commentary. But as his recent opinions in Alleyne v. United States and the Myriad gene-patenting case illustrate, Thomas is much more than a Tea Party mouthpiece. That his views skew conservative is a product not of partisanship but rather of his deep, occasionally confounding dedication to originalist theory. And sometimes that dedication leads this already idiosyncratic justice to cast votes that would please Earl Warren.

Consider Alleyne, a case that deals with the classic liberal bugaboo of mandatory minimum sentences. Most progressives oppose them because they feel they’re racist; a law that raised the mandatory minimum for crack 100 times higher than for powder cocaine, for instance, affected the black community disproportionately.

But for Thomas—who vehemently rejects the notion that blacks are frequently disadvantaged by the legal system—mandatory minimums have nothing to do with race. They have to do with the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee of a jury trial. Thus, in Alleyne (in an opinion authored by Thomas), the court found that any aspect of conviction that contributes toward a mandatory minimum must be specifically proven to the jury. Allen Ryan Alleyne was convicted only of having “used or carried a firearm” in relation to a violent crime, which carries a five-year mandatory minimum. But the sentencing judge decided that Alleyne had, in fact, “brandished” a firearm—a graver crime that carries a seven-year mandatory minimum. In Thomas’ eyes, that distinction is for a jury, not a judge, to make, and so Alleyne’s conviction must be vacated.

To careful observers, Thomas’ ruling should not come as a shock. The justice has consistently defended criminal defendants’ rights, sometimes to a greater degree than his liberal colleagues. (In these rulings, he is intermittently joined by Scalia, who once labeled himself “the darling of the criminal defense bar.”) Thomas is a strong defender of the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment, which guarantees that “in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right … to be confronted with the witnesses against him.” In the 21st century, though, even a minor crime can have a lot of witnesses, and so the court’s conservatives—plus the unpredictable Breyer—have decided that, contra the Confrontation Clause, maybe a few accusatory witnesses can be let off the hook.

That doesn’t fly with Thomas, who provided the court’s fifth vote in 2011’s landmark Bullcoming v. New Mexico. In that case, the court overturned the conviction of a man accused of drunk driving, finding that he had been deprived the right to confront in court the lab technician who tested his blood alcohol level. To Breyer and the conservatives, putting a mere lab technician on the stand is nothing more than a burdensome technicality. But to Thomas, it’s a vital guarantee of America’s founding document.

Thomas is also a consistent protector of private property. (Personal privacy, on the other hand, he gives shorter shrift.) In 2001’s Kyllo v. U.S., Thomas joined Scalia and three liberals in ruling that the use of thermal imaging constitutes a Fourth Amendment “search” and thus requires a warrant. (In another instance of scrambled ideology, John Paul Stevens wrote the dissent in that case.) And just this term, in Florida v. Jardines, a similar split found Thomas successfully defending Americans against a warrantless home visit by a drug-sniffing dog.

Thomas’ record on free speech is spottier. He’s voted against First Amendment protections for lies, symbolic speech, public employees, minors, and prisoners. But Thomas is a fierce First Amendment warrior on one issue: pornography. Thomas has voted several times against regulations designed to prevent minors from accessing porn on the Internet, and voted to ensure that “indecent” sexual material remains accessible to all adults on cable. He’s even supported Americans’ right to view and produce simulated child pornography. And early in his tenure, Thomas joined the liberal bloc in overturning the conviction of a man entrapped in a child-pornography sting.

All of these votes arise from the same philosophy that drives Thomas to rule for unlimited and anonymous corporate electioneering, astonishingly torturous methods of capital punishment, and the deprivation of gay people’s rights. More than any justice in history, Thomas is an originalist, ruling exclusively by the letter of what he views as the Founders’ original intent in writing the Constitution. Because the Founders, for example, condoned “public dissection” and the “embowelling [sic] alive, beheading, and quartering” of prisoners, so too does Thomas. But because, in Thomas’ view, the Founders felt Americans had a right to view graphic sexual material, we still hold that right today. Liberal justices attempt to apply the Constitution’s strictures to the present, adapting its liberties to the needs of modern society. When society proposes a new liberty, like a right to be gay, Thomas rejects it out of hand. But when it begins to encroach on an old one—private property, for instance—Thomas emerges as a defender of freedom.

There’s no freedom Thomas treasures more than the freedom of states to diverge from the federal government. But even Thomas’ hard-core Federalist beliefs can bring him over to the liberal side from time to time. In Gonzales v. Raich, Thomas ruled that the federal government cannot outlaw marijuana grown and sold exclusively in California. (This view found him in disagreement with even Scalia, whose hostility toward drugs apparently eclipses his love of Federalism.) In Wyeth v. Levine, Thomas held that a woman who lost her hand to gangrene due to an improperly labeled medication could sue under state law even when the pharmaceutical company was shielded by federal law. And in Williamson v. Mazda Motors of America, Thomas penned a stirring defense of seat belt legislation, arguing that a state’s strict safety regulations trumped laxer federal ones. Given Thomas’ dedication to states’ rights no matter the cause, some commentators see him as a potential vote for overturning the states’ rights–trampling Defense of Marriage Act.

On the whole, of course, Thomas remains a rock-ribbed conservative, and the surprise that greeted his opinion in Alleyne and last week’s DNA-patenting case is entirely understandable. But just because Thomas’ votes track a generally right-wing pattern does not mean they are preordained by party politics, or even predictable. The principles Thomas follows—unwavering dedication to his own interpretation of the ideas of dead men—may not make much sense to most. But they are principles nonetheless. And Thomas remains dedicated to them, no matter how far left they take him.