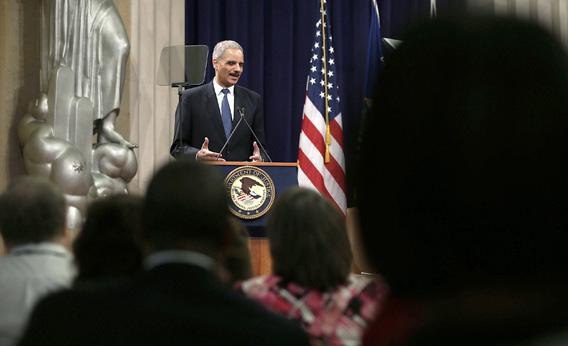

Attorney General Eric Holder has said that he doesn’t want the Obama administration’s leak prosecutions “to be his legacy.” But he has also trumpeted the cases—six and counting—in response to criticism from Senate Republicans. “We have tried more leak cases—brought more leak cases during the course of this administration than any other administration,” Holder said before the Senate Judiciary Committee last year.

This shouldn’t be a source of pride, even the fake point-scoring kind. In light of the Justice Department’s outrageously broad grab of the phone records of reporters and editors at the Associated Press, the administration’s unprecedented criminalizing of leaks has become embarrassing. This is not what Obama’s supporters thought they were getting. Obama the candidate strongly supported civil liberties and protections for whistle-blowers. Obama the president risks making government intrusion into the investigative work of the press a galling part of his legacy.

Here’s the official excuse, from the Justice Department’s letter to AP today and from the daily White House press briefing: “The president feels strongly that we need the press to be able to be unfettered in its pursuit of investigative journalism,” press secretary Jay Carney said. “He is also mindful of the need for secret and classified information to remain secret and classified in order to protect our national security interests.” That sounds like a perfectly reasonable balancing, but in practice, it’s not. Between 1917 and 1985, there was one successful federal leak prosecution. The Obama White House, by contrast, has pursued leaks “with a surprising relentlessness,” as Jane Mayer wrote in her masterful New Yorker piece about the prosecution of Thomas Drake. Of Holder and Obama’s six unlucky targets, Drake is the guy who best fits the whistle-blower profile: He gave information to a Baltimore Sun reporter who wrote “a prize-winning series of articles for the Sun about financial waste, bureaucratic dysfunction, and dubious legal practices” in the National Security Agency. After years of hounding, the case against Drake fell apart, and he wound up pleading guilty to one misdemeanor. No jail time.

The Drake prosecution started under President George W. Bush. So did the leak prosecution of Jeffrey Sterling, the former CIA officer charged with disclosing information about Iran to James Risen of the New York Times. But Obama’s Justice Department has also launched its own prosecutions, as the AP probe underscores. As Scott Shane and Charlie Savage pointed out last year in the New York Times, it was in 2009, the first year of Obama’s presidency, that DOJ and the director of national intelligence created a taskforce that “streamlined procedures to follow up on leaks.” At the same time, the increasing prevalence of electronic records made investigations easier. The result, as Shane and Savage write, is that while the Justice Department used to be “where leak complaints from the intelligence agencies went to die,” now they are being kept alive.

Nor is there a law or a Supreme Court reading of the Constitution to kill them. Timothy Lee lays it out nicely on Wonkblog so I don’t have to: You don’t have a right to protect information that you give to someone else. That’s what the Supreme Court thinks phones calls are—the act of dialing. This could apply to the content of email that lives in the cloud—Gmail! Journalists get the benefit of a rule the Justice Department has made for itself, supposedly to prevent interference with the First Amendment–protected work of reporters. The rule says that the attorney general has to approve the demand for records, and that DOJ lawyers have to take all the other reasonable steps they can before drawing up a subpoena, and then write it as narrowly as possible. But the AP probe, and other examples of surveillance of reporters, show that the rules only mean so much.

In Tuesday’s letter to the AP, Deputy Attorney General James Cole said that in this case, DoJ “undertook a comprehensive investigation, including, among other investigative steps, conducting over 550 interviews and reviewing tens of thousands of documents, before seeking the toll records at issue.” But that doesn’t really tell us whether this ordering up of phone records was a valid response to an egregious leak that breached national security, or another Drake affair. The AP thinks the Justice Department wants to know how it reported a story in May 2012 about the CIA’s foiling of a plot by al-Qaida’s Yemen affiliate to plant a bomb on a plane. Here’s the story. The AP said at the time that it actually held off publishing for a week, in response to White House and CIA requests, “because the sensitive intelligence operation was still under way.” The government knows things I don’t, of course, but reading the story now, it’s hard to see a threat to national security in the content—it’s just not all that detailed.

Whether a leak threatens national security is clearly not the standard Holder and his department are using. And the problem is that the standard is up to them. The 1917 Espionage Act, the basis for most of these cases, was written to go after people who compromised military operations. Back in 1973, the major law review article on that statute concluded that Congress never intended to go after journalists with it, or even their sources. Since then, legal scholars have proposed various ways of narrowing the Espionage Act—University of Chicago law professor Geoffrey Stone wants to limit the law’s reach to cases in which there’s proof that a reporter knows publication will wreck national security without contributing to the public debate. But Congress has done nothing of the sort. Wouldn’t it be nice if the Republicans who are indignant over the AP investigation got serious about reform? Somehow, I doubt it. Instead, with a Democratic White House leading the charge, it’s hard to see who will stop this train.