If you’re trying to understand whether the administration’s targeted killing program is lawful, you’d have a tough time figuring it out from some of the legal language flying around this week. On the right, Eric Posner tells us in Slate that the Justice Department’s leaked white paper on drones confirms what he’s long argued, that the president has the power to do whatever he wants in the name of fighting terror. On the left, Mary Ellen O’Connell insists that the white paper’s justifications are so manifestly false that there is little difference between the Obama DOJ justifying targeted killing, and the Bush DOJ justifying torture.

Neither has it right. While torture is never, under any circumstances, permitted by law, targeted killing sometimes can be. The question—and it’s a big one—is when.

The DOJ white paper doesn’t succeed in answering the question. Not because its arguments, such as they are, get the law plainly wrong. But because the paper’s authors never quite commit to saying what the law is.

To say when targeted killing is legal, the white paper would have to do two things. It would have to identify a source of authority in the U.S. Constitution, or in laws passed by Congress, that gives the president the power to use force. And it would have to identify and apply the U.S. and international laws that limit when such force can be used.

Start with the source of authority. The white paper says that the president has some power to use force as part of his “constitutional responsibility to defend the nation.” Indeed, the Supreme Court has recognized that Article II of the Constitution gives the President at least some authority to, as the framers put it, “repel sudden attacks,” without having to go to Congress first for permission—in other words, to play defense in the moment. It’s not hard to imagine an argument that the government targeted U.S. citizen Anwar al Awlaki in Yemen because of a discovery that he was about to launch a particular, sudden attack. But the paper doesn’t actually make that argument. It’s not just that al Awlaki goes unmentioned. So does Article II. And true enough, the administration has been at pains, in court challenges to its detention power at Guantanamo, to avoid resting its claim of authority on the president’s constitutional power alone—precisely because such claims of authority can be overly broad.

Perhaps another tack, then? There’s also the Authorization for Use of Military Force, passed by Congress in 2001, which gives the president the power to use “all necessary and appropriate force” against the organizations responsible for the 9/11 attacks. Since 2001, Presidents Bush and Obama, the Supreme Court, and Congress have all said this “necessary and appropriate force” includes the power to detain, even the power to detain American citizens picked up in Afghanistan. The same logic by which all three branches of government have agreed the law authorizes detention—because detention is a necessary incident of war—supports the argument that it authorizes lethal targeting as well.

But as the executive, Congress, and the courts have also recognized, the power granted by the AUMF only extends as far as what is allowed by the international laws of war. And there are a lot of those laws. For now, let’s just take one of them, and for the sake of argument, state it in a way that gives the administration the widest possible latitude for targeting. According to the relevant treaties, and the International Committee of the Red Cross (the world’s most recognized interpreter of the law of war), members of organized armed groups that do not represent states may be targeted in war either if they are directly participating in hostilities when they’re targeted, or if it was their “continuous function” to prepare for, command, or take part in acts that amount to direct participation in hostilities. Reports about al Awlaki’s role suggest he might fit squarely into the “continuous function” category of potential targets.

And yet the white paper never discusses the concept of direct participation. It never talks about the treaty provisions, or the Red Cross guidance. More simply, it doesn’t identify a legal rule about who is targetable under the law of war. That leaves us to speculate about the reason for the omissions. Does the Obama administration think the “continuous function” standard isn’t the rule? Or is this indeed the rule DOJ lawyers had in mind, but they just didn’t want to adopt it in full (including the very next part of the Red Cross guidance, which says recruiters, trainers, financiers, and propagandists generally cannot be targets)?

The white paper avoids commitment this way throughout. International law says the use of force is sometimes justified in national self-defense, if an attack is imminent. But the paper never states this rule of self-defense: It just raises concepts of imminence in an otherwise unrelated discussion of the guarantee of due process of law in the Constitution.

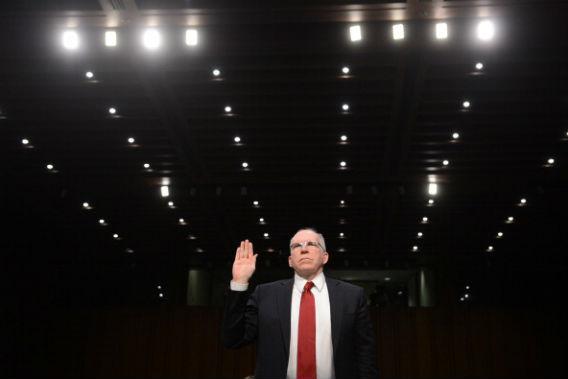

Why should it matter so much, to say what the law is? In his testimony before the Senate on Thursday, John Brennan, the president’s choice to be the next CIA Director, explained this well. The Justice Department must “establish the legal boundaries within which we can operate,” he said. Brennan is right. Applying the law means drawing lines—in something other than invisible ink.