Earlier this month, Jared Loughner was sentenced to life in prison at a sober proceeding in which survivors of his terrible shooting spree in Arizona, and their families, recognized the role his schizophrenia played in his crimes. They talked about their understandable hurt and anger, and they also recognized that Loughner didn’t get the mental health care he needed. (Mark Kelly, the husband of former Rep. Gabby Giffords, whom Loughner shot in the head, usefully highlighted the expiration a decade ago of the federal law that banned the sale of the rapid-fire ammunition clips Loughner used.)

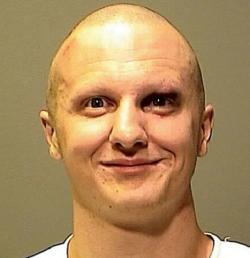

It took months of medication and treatment for Loughner to understand the charges against him. That comes as no surprise, given the disturbed-looking photos of him after the crime. And the country got a similar view of violence and untreated mental illness in James Holmes, the 24-year-old who shot up a movie theater in Aurora, Colo., in July. Both Loughner and Holmes spiraled out of control while enrolled at a university yet fell through the holes of the health care net that should have caught them. This is a story we’ve been hearing since at least the 2007 mass killing by a student at Virginia Tech.

The mental illness of criminal defendants, however, is not of current interest to the Supreme Court. This week, the justices turned down a case challenging Idaho’s complete lack of an insanity defense. In Idaho, “mental condition” is not a defense to any charge of criminal conduct. In the case the Supreme Court won’t hear, John Joseph Delling, a paranoid schizophrenic, shot and killed two of his friends and wounded a third while seized by the delusion that he was a “type of Jesus” and that his friends were “taking his energy” in a way that would kill him. A psychologist testified that he truly—and delusionally and tragically—believed he had to stop his friends to save his own life.

Delling, like Loughner, had to be medicated for a year before he could be found competent to stand trial. At that point, the judge found that when he committed the killings, he was unable to appreciate the wrongfulness of his actions. But Delling was still guilty of murder, because there was no insanity defense for him to plead. Think about that for a minute: The state was saying that a man who was so insane that he could not understand that it was wrong to kill two of his friends was just as culpable as a sane person. The Idaho Supreme Court agreed. And now the U.S. Supreme Court has declined Delling’s challenge to these rulings, which means it has ducked the question of whether the Constitution requires the states to provide a traditional insanity defense. Idaho is an utter outlier here. That’s true because 46 states recognize that the ability to distinguish between right and wrong matters for holding a person criminally responsible for his or her actions. It’s true because the American Psychiatric Association is on Delling’s side. And it’s also true because societies have recognized since ancient times that people whose mental illness destroys their judgment, in the way that Delling’s schizophrenia did, are not culpable in the same way that the rest of us are. Delling’s lawyers cite “Hebraic, Roman, and early Muslim law.” Also Homer’s Iliad. William Blackstone provided for an insanity defense in his 18th-century treatise. The best known and most durable version of the plea is the 1843 M’Naghten rule, which allows a defendant to try to prove that he didn’t know right from wrong, or the “nature and quality of the act he was doing,” because of “a defect of reason, from disease of the mind.”

M’Naghten isn’t the last word: State legislatures and judges, including my grandfather, Judge David L. Bazelon, have tried to come up with better or broader standards that would allow psychiatrists to testify about the full extent of a defendant’s mental illness, not just whether he can tell right from wrong. That has proven hard to do. And as it stands, the insanity defense plays only a tiny role in the everyday criminal justice system and succeeds in one-quarter of 1 percent of cases (though more than 10 percent of the prison population is mentally ill).

But the baffling, dismaying point to make about John Joseph Delling is that Idaho doesn’t even provide the old protection of M’Naghten. As the state’s courts themselves say, Idaho’s rule “may allow the conviction of persons who may be insane by some former insanity test or medical standard, but who nevertheless have the ability to form intent and control their actions.”

Justice Stephen Breyer, joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Justice Sonia Sotomayor, dissented from the Supreme Court’s decision to ignore Delling’s plea. Breyer explains the hole in Idaho’s law by comparing a defendant who kills someone thinking his victim is a wolf to a defendant who kills someone thinking that a wolf has given him supernatural orders to carry out. In neither case can the defendant truly understand what he has done. But in Idaho, the mentally ill defendant who is taking orders from a wolf has no insanity plea to invoke.

One more woeful note about the direction in which this area of law is moving: The last time the Supreme Court considered the scope of the insanity defense, in 2006, it was to affirm the conviction of a schizophrenic 17-year-old in Arizona, Eric Clark, who was not allowed in the courts of his state to offer evidence of his mental illness to address the state’s claim that he had killed an officer knowingly and on purpose. This is also a bad rule, even if it’s not quite as bad as Idaho’s. Perhaps it helps explain why despite all the acknowledgment of Jared Loughner’s schizophrenia at his sentencing, the judge presiding over his case said he was not insane at the time of the shooting. “He knew what he was doing,” the judge said. Never mind that Loughner will probably spend the rest of his life in a psych ward. States like Arizona and Idaho are becoming more and more vindictive toward the mentally ill and less and less willing to uphold the tradition of reckoning with the diminished capacity their illness produces. And the Supreme Court is OK with that.