How does the brave new world of campaign financing created by the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision stack up against Watergate? The short answer is: Things are even worse now than they were then.

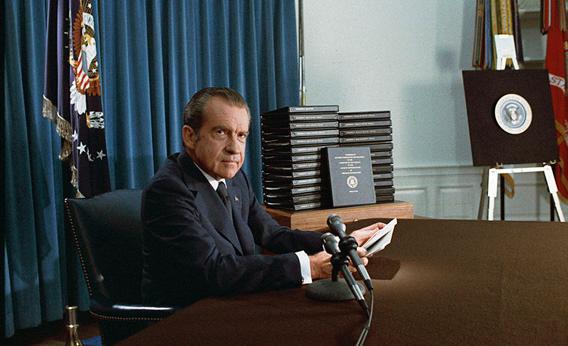

The 1974 scandal that brought down President Richard Nixon was all about illegal money secretly flowing to politicians. That’s still a danger, but these days, the biggest weakness of our campaign finance system is not what’s illegal, but what’s legal. As Dan Eggen of the Washington Post put it, “there’s little need for furtive fundraising or secret handoffs of cash.” The rules increasingly allow people and corporations with great wealth to skew public policy toward their interests—without risking a jail time, or a fine, or any penalty at all. It’s an influence free-for-all.

The Washington Post reminds us what the country faced in the time of Watergate: “Money ran wild in American politics. One man, W. Clement Stone, gave more than $2 million to President Richard M. Nixon’s 1972 reelection campaign. The Watergate break-in was financed with secret campaign contributions. Fat cats plunked down cash for ambassadorships, and corporations for special treatment.” Fred Wertheimer, who has been pushing for campaign finance reform for decades, recounts that the corruption of old got results: “The dairy industry gave $2 million to the Nixon campaign and soon got the increase in dairy price supports they were seeking. Nixon overrode his Agriculture Department’s objection to put these supports in place.”

Today, no one gives an illegal $2 million contribution directly to a presidential candidate. If you’re Sheldon Adelson, why break federal law, which caps individual donations to a candidate at $2,500, when you can just give $100 million to super PACs and other organizations supporting Mitt Romney’s presidential campaign? Yes, to stay in the law’s good graces, these groups must follow the Federal Election Commission’s rules barring certain forms of “coordination” with a candidate’s campaign. But the candidate may solicit money for the group; his former campaign workers, friends, and confidantes may run the group; and friends and family can give unlimited sums to support his candidacy. All of this now happens not in the shadows, but with the blessing of the courts and the FEC.

Even the $2,500 contribution limit on direct contributions to candidates (really $5,000, because people can give to a candidate once for the primary and once for the general) is barely a road block to big givers. Both Romney and Obama have set up “joint victory” committees, sharing contributions among the candidate campaign and state and local parties. The real current limit, set by federal law on individual contributions to a presidential candidate and supporting party committees, is $75,800.

Corporations as well as individuals have plenty of legal ways to throw their money around. Back in the Watergate days, American Airlines funneled secret money to the Nixon campaign through Beirut. It was complicated, shady, and illegal. These days, as the New York Times has explained, corporations can give millions legally to party conventions, getting special perks. And thanks to Citizens United and the FEC, corporations have the same leeway as individuals to give to super PACs, the U.S. Chamber, and other groups.

In Watergate, illegal donations bought tremendous influence, but at a risk. Lifting the cloud of illegality has simply emboldened big donors. This is the point Justice Kennedy missed when he said that “independent” expenditures—money that goes to groups that help candidates get elected, rather than candidates themselves—doesn’t corrupt or create the appearance of corruption. And it’s the point Matt Bai missed in his New York Times Magazine article this week, by claiming that Citizens United did not make much difference to the world of campaign spending. Before the chain of events unleashed by the 2010 Supreme Court ruling, if Sheldon Adelson tried to give $100 million to outside groups to support a presidential candidate, he would have faced a criminal investigation and potential charges. The big 527s from previous elections, including the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth and Americans Coming Together, faced hefty fines for trying to do illegally what super PACs can now do legally: specifically, setting up a group to take unlimited contributions to influence federal elections.

There is one big danger today that does hark straight back to Watergate. It’s the proliferation of secret 501(c)(4) groups that take money without publicly disclosing their contributors. The people and companies who give to these groups are not revealed to the public, though of course they are often eager to reveal their identity to the politicians they are supporting. These contributors get all the perks of influence without any of the public scrutiny. And if we can’t trace their connections to the actions of elected representatives, we’re much less likely to find out about illegal quid pro quo. Which is why we should improve our disclosure laws—which Republicans have refused to do because they see electoral advantage in secrecy.

But even with better disclosure laws, we’d still be in worse shape now than we were at the time of Watergate. Increasingly, large sums contributed by the wealthy affect who wins elections and what the winners do once in office. Even well-meaning officials who won’t want to bend to the Sheldon Adelsons of the world have to find other friends with cash so that they can fight back. Those friends will want their own special access, and the people they help elect have every incentive to give it to them.

The new campaign finance order isn’t held up by paper bags full of cash. That’s the old way. When corruption is conveniently legal, you can pay by check or credit card.