Last week, the ACLU and the Center for Constitutional Rights sued the government over the drone strikes that killed American citizens in Yemen in 2011. The suit is almost surely a loser. But the rationale the courts will probably use for disposing of it, if not the outcome, is troubling : It shows how it’s nearly impossible to win compensation if you say you’ve been harmed by anything that relates to U.S. national security.

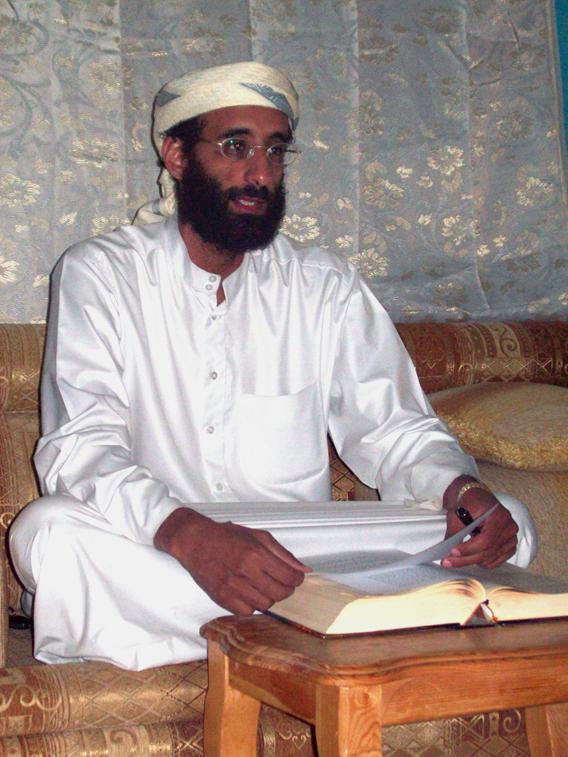

A main target of the drone strikes was Anwar al-Awlaki, an American-born cleric who had long been active in al-Qaida’s Yemen-based affiliate, and who inspired and helped direct several attacks on the United States, including the attempt by the “underwear bomber” to blow up a U.S.-bound airline on Christmas in 2009. Another U.S citizen traveling with al-Awlaki, Samir Khan, was also killed; he grew up in the United States and became a leading online propagandist of jihad. A few weeks later, a second drone strike in Yemen killed several other people, including the cleric’s son, Abdulrahman al-Awlaki, also a U.S. citizen and just 16 years old at the time. Apparently the targets of that strike were al-Qaida militants, not the boy.

The new lawsuit alleges that the killings of the al-Awlakis and Khan were unconstitutional, and seeks money damages from the Secretary of Defense, Director of the CIA, and other high-ranking U.S. national security officials. (President Obama approved the strikes, but he isn’t named because the Supreme Court ruled in 1982 that presidents are immune from such suits.)

On the merits, this suit is groundless. Its filing mostly reflects how groups like the ACLU, which has vigorously opposed many aspects of the war on terror pursued by Bush and Obama, use the courts to generate publicity and extract information. The problem is that the courts will most likely toss the lawsuit before they even get to the constitutional claims, simply because the suit seeks money damages from federal officials involved in national security. Victims who seek compensation in cases involving national security almost never get it—for reasons that don’t make much sense.

First, here’s why there’s no winning constitutional claim: Our founding document does not prevent the U.S. government from killing U.S. citizens when they have joined the enemy in an armed conflict, as Anwar al-Awlaki and Khan did, or when they are located in the same place as enemy fighters and killed as collateral damage, as was Abdulrahman al-Awlaki. If the Constitution meant what the ACLU and CCR say it does, President Lincoln and the Union could never have won the Civil War. Early on, many war critics asserted that because Confederates were U.S. citizens, the U.S. government could not use military force against them—could not treat them as foreign military enemies—but instead had to give them constitutional due process, like the police making an arrest. Luckily for the Union, President Lincoln, supported by allies in Congress and later by the Supreme Court, decided that U.S. citizens engaged in large-scale armed rebellion were not protected by the Constitution. This has been our legal understanding ever since. There were U.S. citizens in the ranks of enemy armies during both World War I and World War II, and no one thought that the U.S. Constitution protected them from being killed. The al-Awlakis and Khan are like them, even though they’re not officially serving in a nation’s army, because hostilities with terrorist groups can rise to the level of war, and the United States considers itself to be in just such an armed conflict with al-Qaida and its affiliates.

But none of that’s likely to come into play in court, because the demand for money damages on its own will get the case thrown out. And this is the part we should worry about. Over the last several decades, the Supreme Court has made it harder and harder for people who say they’ve been harmed by the federal government to sue the responsible officials for money. The court has said that damages suits are highly “disfavored” because they deter officials from vigorously performing their duties and pull the courts into the realm of policy-making that the Constitution reserves to Congress and the president. As a result, since 9/11, the lower courts have refused to allow money damages suits for all kinds of excesses, including torture, rendition, extended military detentions, and even the illegal outing of Valerie Plame as a CIA operative.

This is all especially odd because even as courts toss suits for requesting compensation, they have allowed other cases to go forward when they seek intrusive court orders directing how the government should carry out national security policy. For example, Guantanamo detainees can seek orders requiring the government to release them. In other cases, advocacy groups, writers, and activists have successfully asked the courts to bar the government from carrying out entire programs, including the FBI’s effort to gather telecommunications subscriber information and the law governing the detention of enemy combatants passed last year.

In effect, the federal courts are saying to people who believe they are harmed by government action: If you ask us to bring government operations to a halt, sure, no problem. But if you ask for money to compensate for harms you suffered, no, that is way too intrusive. This is precisely backward. It should be easier to get to court to seek compensation for a wrong at the hands of government officials, and it should be harder to get to court if you’re trying to direct how the government carries out national security policy. For the first century or so of American history, that was how things worked. People wronged by federal officials had a pretty good chance of winning damages, while people who asked the courts to step in and tell the president and Congress what to do were generally rebuffed. That made sense. Now, by contrast, the courts are getting it backward, as the al-Awlaki suit will surely show.