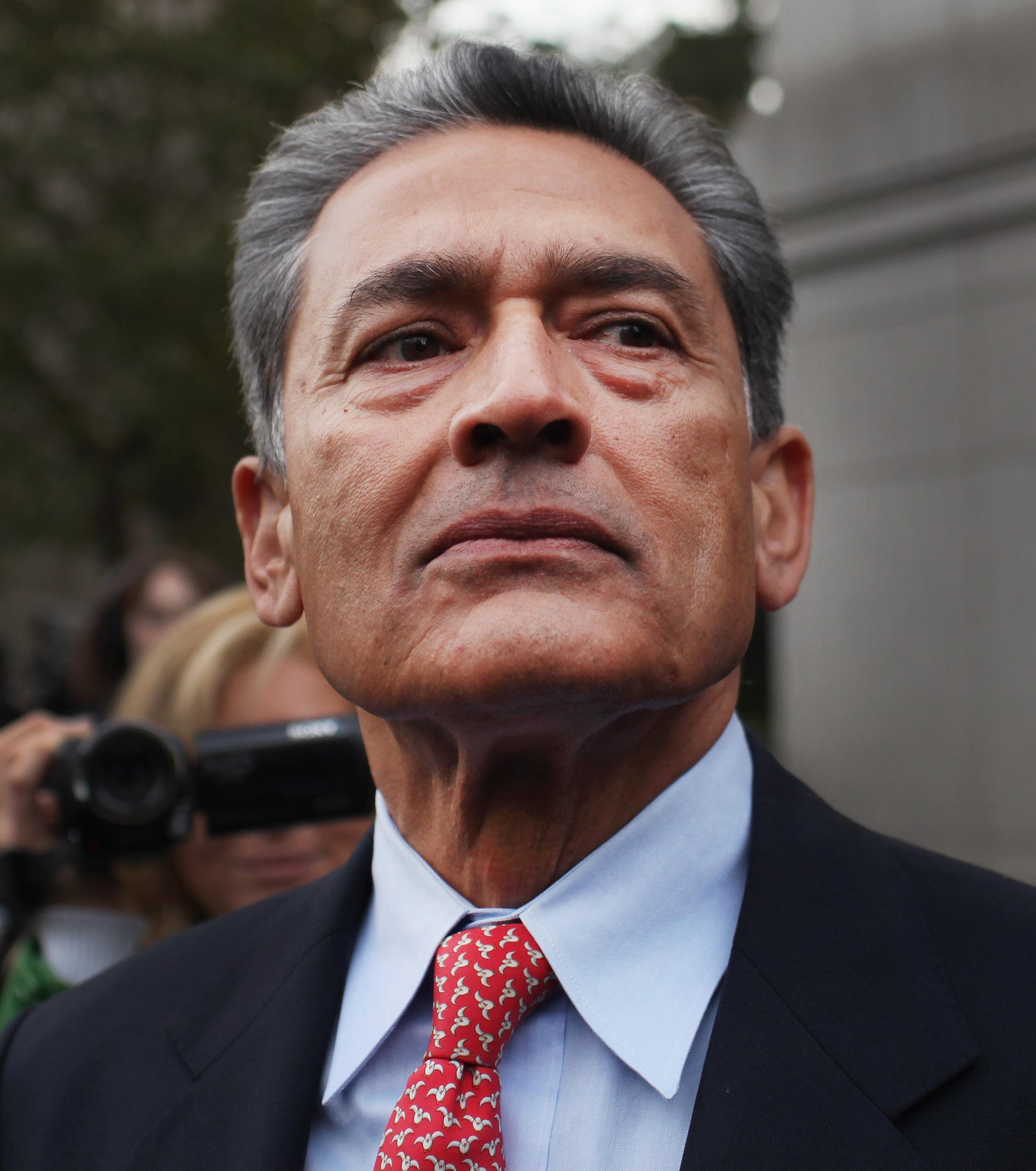

On Monday, former McKinsey & Company chief executive Rajat Gupta goes on trial for insider trading. Gupta is accused of sharing secrets about Goldman Sachs and Proctor & Gamble with Raj Rajaratnam, the former chief of hedge fund giant Galleon Group, who was convicted in October 2011 of the same crime.

Gupta and Rajaratnam are the biggest names in the government’s 3-year-old crackdown on illegal trading on Wall Street. So far, prosecutors have convicted or elicited guilty pleas from more than 60 traders, hedge fund managers, and other professionals. Federal authorities said in February that they are investigating an additional 240 people for trading on inside information. About one half have been identified as “targets,” meaning that government agents believe they committed crimes and are building cases against them. Officials are so serious about their efforts that they even produced a public service announcement about fraud in the public markets. It features Michael Douglas, the Academy Award winning actor who played corrupt financier Gordon Gekko in the 1987 hit film Wall Street. His character’s crime, of course, was insider trading.

Nailing smartly dressed, smooth talking financial types who embrace Gekko’s “greed is good” credo makes for great headlines. It even got New York’s top federal prosecutor, Preet Bharara, a spot on the cover of Time magazine, which celebrated him as the man who is “busting Wall Street.” But pouring money into criminal insider trading cases is a huge waste of public resources. There is a much more cost-effective way to go after this particular form of fraud, and switching to it would free up prosecutorial resources to fight other economic crimes that pose a far greater danger to Main Street investors.

Insider trading is the act of buying or selling securities for financial gain or other benefit based on confidential corporate information that likely would affect a stock’s price if it were to become openly known. An “insider” is any person with access to that kind of information, like an officer or director of a public company, or a friend or family member of an employee. Criminal liability for insider trading arises when employees of publicly traded companies breach the fiduciary duty owed to their employers. It can also come about when people misappropriate (that is, steal) proprietary corporate information to benefit themselves or people they know.

Trading on inside information, though, is fundamentally different than other types of financial fraud. It doesn’t cause other investors to feel a pinch in their pockets. It doesn’t trigger layoffs. It doesn’t bankrupt companies or shutter factories. And it doesn’t wipe out pension plans or 401Ks. James Altucher, a Huffington Post financial columnist, has made the case that insider trading actually should be legal for the sake of transparency: If investors can see that corporate insiders are buying and selling stock, the market will more accurately reflect a company’s true condition and value.

Insider trading cases are also expensive for the government to prosecute. Well-heeled financial professionals like Gupta and Rajaratnam have the means to hire legions of high-priced lawyers to defend them and challenge the government at every turn. Rajaratnam alone reportedly spent over $40 million on his defense. Furthermore, the government’s latest tool of choice for these cases—wiretaps—requires lots of investigator man hours. Wiretaps also prompt protracted pretrial battles with defense lawyers, who contest the admissibility of recorded conversations.

We’d be better served if the government spent its limited investigative capital bringing actual thieves to justice, such as Ponzi-schemers like Bernard Madoff or Allen Stanford. Or people who defraud corporations, like the group of fraudulent medical clinic operators, doctors, and lawyers who were charged in February with cheating insurance companies out of more than $279 million. Or those who rip off the government itself, like the four people, including three bank employees, who were accused in January of filing $5 million worth of fraudulent tax refunds.

This isn’t to say the government should pass completely on pursuing insider traders. They are, after all, using an unfair edge—information they have that you and I don’t—to profit. Their conduct has a corrosive effect on the public’s trust in the markets. But the government has at its disposal alternative methods for going after traders on insider information—civil charges that generate pocket-book penalties instead of criminal ones that lead to prison sentences. Civil charges are more proportional to the wrongdoing, less expensive to prosecute, and still get the job done.

The SEC has filed parallel civil lawsuits against everyone charged with insider trading in the past three years. It has sought fines and disgorgement of ill-gotten gains. Rajaratnam was slapped with a $92.8 million penalty. The hedge fund Pequot Capital and its former CEO, Arthur Samberg, agreed to pay $28 million to settle insider trading charges. In these instances, the SEC doesn’t have to prove its cases beyond a reasonable doubt, which makes them easier to win. That’s part of the reason the SEC was able to extract $550 million, the largest penalty ever against a financial services firm, from Goldman Sachs for having misled investors about a complex mortgage product. The SEC scored this victory just three months after filing suit—without costly litigation and without a trial.

Taxpayers pay for snagging insider traders. They could get a better return on their investment. If the government concentrated on socking insider traders with big money penalties, it would spend less, make more, and still police the markets. That would be, in the parlance of Wall Street, a good deal.