Attorney General Eric Holder gave a speech earlier this month that was covered in the press primarily for one thing: its legal defense of the Obama administration’s policy for targeted killings of terrorists who are U.S. citizens. Neither the policy nor its defense is surprising. The policy fulfills an Obama campaign pledge and has become a central tenet of the president’s counterterrorism strategy. More surprising, and almost completely overlooked, was Holder’s robust defense of military commissions, which he described as “essential to the effective administration of justice.” Most people had thought that commissions would die under the Obama administration since Candidate Obama had campaigned against them. But as Holder’s endorsement indicates, military commissions have made an improbable comeback.

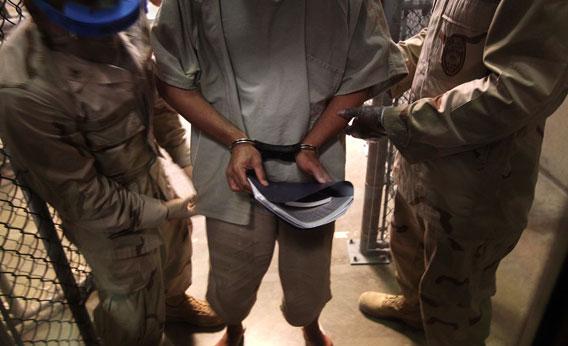

Military commissions are courts run by the military to try enemy forces for war crimes and related offenses. They have special rules about evidence, secrecy, and other matters that are tailored for the exigencies of war and that make it easier to convict a defendant than in an ordinary civilian court. Presidents have deployed commissions in one form or another in most major wars in American history. But the ones created by George W. Bush in November 2001—without any new input from Congress and with relatively few defendant rights—sparked enormous controversy and were beset by legal and political difficulties throughout his administration.

In his first week in office, President Obama temporarily suspended these commissions. The New York Times editorial board, reflecting progressive conventional wisdom, viewed the temporary halt as a “legal nicety,” reasoning that “[t]here is no good reason to restart these trials.”

But it was no legal nicety. An intensive review by the Obama administration revealed that, as the Bush administration had always claimed, many dangerous terrorists held at Guantanamo Bay were incapable of being tried in a civilian court. The responsibilities of the commander in chief—responsibilities impossible for Obama to appreciate before assuming office—made it unthinkable to release these detainees if there were any legal basis for holding them.

Despite the controversies of the Bush years, and indeed because of them, commissions had become a lawful option for the new administration. The Supreme Court had struck down the original Bush commissions in 2006 but implied that congressionally approved commissions could pass legal muster. Congress subsequently enacted a comprehensive statute governing military commissions that conferred unprecedented defendant rights. From a contentious legal and political process emerged two valuable lessons: Military commissions served an indispensable role in the war against al-Qaida, and they could fulfill this role even while taking legal protections for defendants very seriously.

The Obama administration quickly concluded that it would continue to use military commissions. As President Obama explained after five months in office, commissions “allow for the protection of sensitive sources and methods of intelligence-gathering; they allow for the safety and security of participants; and for the presentation of evidence gathered from the battlefield that cannot always be effectively presented in federal courts.” This was precisely the Bush administration’s rationale.

The Obama administration sought and received from Congress additional reforms to commissions to disallow certain evidence obtained from coercion, to make it harder for the government to use hearsay evidence, and to give detainees more freedom to choose attorneys. These reforms were not big changes from the earlier congressional effort, but they increased the reliability of rulings and gave commissions a second, bipartisan stamp of congressional approval. Congress yet again gave these bodies its approval in the 2011 defense authorization law—approval that, unsurprisingly, mirrors widespread support for commissions by the American people.

Today, the Obama administration is deploying commissions aggressively. It has secured four convictions in the past three years. That is more than the Bush administration won in the previous seven years. And it restarted the process of trying senior al-Qaida officials responsible for the 9/11 attacks—a process delayed by Attorney General Holder’s failed attempt to try them in civilian court.

The commissions, of course, still have critics who question their fairness and effectiveness. But the results emerging from commissions belie these criticisms. One indicator of commissions’ fairness is that their sentences for convictions have been lower than in similar cases in civilian courts. One indicator of their usefulness is that al-Qaida operative Majid Khan recently pled guilty to several crimes in exchange for a 25-year sentence and an agreement to testify against senior al-Qaida figures in future commission trials. The Obama administration is even considering using military commissions to prosecute a non-al-Qaida operative, Hezbollah-linked Ali Musa Daqduq, who is currently in Iraqi custody accused of organizing attacks on American soldiers in Iraq.

The revival and acceptance of military commissions is a happy development in the long war against Islamist terrorists. These commissions provide the president with a third tool for terrorist incapacitation in addition to civilian trials (which have evidentiary rules that are sometimes too demanding for battlefield captures, and which in any event Congress has banned for GITMO terrorists) and military detention (which many believe is too lax in its criteria for indefinite incapacitation).

The revival of commissions is also a testament to the underappreciated success of our constitutional system in the last decade. That system pushed President Bush to accept a more rigorous commission system than he wanted. Along the way, it legitimated commissions in ways that President Obama, contrary to his initial inclination, found difficult to resist. Neither president got what he wanted. But as Holder’s powerful endorsement indicates, commissions now enjoy widespread political and legal support, and they finally seem to be working.