One rainy morning in December, I handed a guard my bag and stepped through a metal detector into the impeccably clean office of the German consulate in Los Angeles. I was soon gestured forward to the counter, where I handed over a copy of my birth certificate, passport, and my mother’s certification of naturalization. The clerk looked over the paperwork and thanked me. Three months later, I received notice that my application had been granted. And just like that, without ever having set foot in Germany, I became a German citizen.

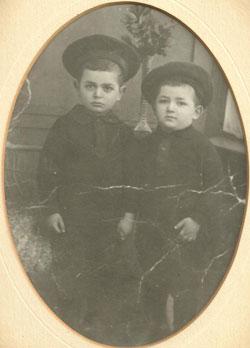

The path to my repatriation began in 1934, when my grandfather, stripped of his right to an education and a job by the Nazis’ Nuremberg Laws, fled Germany and landed in New York City. Alone but for one older brother, he gave up his dream of becoming a doctor, took a series of factory jobs, and eventually started a house-painting business. In 1941, the Nazis took the Nuremberg Laws to their logical conclusion and passed the “Eleventh Decree to the Law on the Citizenship of the Reich,” stripping my grandfather and all Jews who had fled before or during the war of their German citizenship.

Despite the fact that my grandfather could be counted an American success story, he saw only what he had lost. Carrying to his grave his rage over all that had been stolen from him, he cut off any connection to his former homeland. He cast off his German name, took on the strictures of Orthodox Judaism, and obtained American citizenship. He did everything in his power to erase his past.

Growing up in New York, in the ‘70s and ‘80s, in a community shaped by the losses of the Holocaust, I understood that any hint of the Teutonic was suspect. Our grandparents and great-grandparents were named Siegfried or Teresa, but we were a cohort of biblical Rebeccas and Davids and American Jennifers and Jasons. And we embraced Israel, complete with the image of the macho, militaristic Sabra, ready to stand up to all enemies. The word “German” evoked raw emotions outside the Jewish community, too. Back then, when movie villains were often Nazis, Americans often viewed Germans as having personally perpetuated the horrors of World War II, no matter who they were or what role they’d actually played in the war. No one I knew bought German-made electronics or cars, either. To forgive the Germans was unthinkable. To support them economically was a form of treason.

At the same time, we saw how much our second-generation parents valued the family heirlooms that managed to survive the war. Our Hummel figurines and Meissen china sets were a bridge, reminding our families, I suspect, that we were once accepted in the place that had turned on us so completely.

Only as an adult, living far from home, did I begin to question the premises of these beliefs. Perhaps we shouldn’t paint all Germans with such broad strokes. Perhaps we should begin to look at the efforts that Germans have made to come to terms with their past.

It can take years to move from suspicion to a more sympathetic and nuanced worldview. Or it can take a week. When my mother was invited by friends to visit Berlin a few years ago, she agonized about setting foot in the country that had expelled her father and decimated Jewish Europe. Could she really give her tourist dollars to Germany? Should she personally participate in its rehabilitation, or did she owe it to her father, and to the all the Jews who didn’t make it out alive, to boycott? Those were the simple questions. It was more complicated to ask if she should open herself to seeing Germany as more than the frightful landscape of her nightmares. In the end, she went. She visited museums and went to the opera. It’s one thing to feel generalized resentment toward a place and its people. It’s quite another to see them go about their lives, to talk with them and see them in hotels, restaurants, theaters, and opera houses.

I was glad that my mother, who had clung to her father’s ideas for so long, had opened herself up to seeing Germany in a new light. But I never thought she would want to be German. My mother couldn’t—or wouldn’t—tell me why she wanted to do this. But because of her family history, she could do this. During the beginning of the Marshall Plan in the late 1940s, West Germany wrote and ratified a new constitution. The Basic Law, as it is called, includes this short statement in AAArticle 116, Part 2: “Former German citizens who between January 30, 1933 and May 8, 1945, were deprived of their citizenship for political, racial or religious reasons, and their descendants, shall be re-granted German citizenship on application.”

With this, Germany retroactively re-enfranchised those whom the Nazis had rejected. Although the law theoretically applies to political dissidents and Roma communities, the major beneficiaries have been the Jews. It’s hard to say how many people have been naturalized, but word has spread in the last five to 10 years. Advertisements run in Jewish publications broadcasting the statute’s provision. About 100,000 Israelis hold German citizenship (although it’s not known how many do so through birth or marriage, and how many through this statute). Dozens of Americans now put in applications at German embassies and consulates each month. Americans like Evan Kaufmann, a hockey player profiled recently by the New York Times, who plays for the German national team.

Coming from a country that still refuses to enfranchise its large and well-established Turkish community, Article 116, Part 2 was an act of repentance–and also an admission of Germany’s loss. In the years since the Holocaust, Jews in the United States and around the world have contributed to the world’s progress in innumerable ways, producing Nobel Prize-winning scientists, leading writers and artists, influential politicians, and prominent business leaders. Not all have German roots. Other European countries lost sizable Jewish populations to genocide and migration. Poland, which kicked its Jews out in 1968 and stripped them of citizenship, now has a program like Germany’s to repatriate the descendants.

Once my mother went through the process, she told me that I could take German citizenship for myself and my children, too. The absurdities weren’t hard to see: I don’t speak German. I haven’t visited Germany or thought of living there. It’s never even been on my list of top five places to see before I die. And yet the possibility tempted me, for both pragmatic and historical reasons. These days, with anti-American sentiment raging around the world, it is comforting to know that I can travel on a German passport. It’s also reassuring that if the day comes when I can’t find or afford health insurance, I can go to a country where I won’t have to worry about going broke if I get sick. In just 70 years, inconceivable as it may seem, being both Jewish and German has become a potential form of protection rather than a fatal liability.

My German citizenship is not a symbolic gesture connecting me to my grandfather’s memory. He would have hated the idea. He would have felt as betrayed by us for wanting to be German as he once was by those who told him he wasn’t German enough. Instead, I think of my new passport as a form of nonmonetary reparations. At present, I’m not sure exactly what being German, on paper, really means. Could I vote? Should I vote? Probably not. I was born and educated in the US. My life is here. But I have two young children, and while they are the great-grandchildren of a German Jew who rejected his past, they are also the descendants for whom the Basic Law was written. One day, they may choose to return to Germany. They may choose to live there (or, as citizens of the European Union, anywhere else in Europe). My daughters’ wide-open future may end up repudiating what the Nazis set out to accomplish. They may become the Jews Germany once thought it didn’t need.