In the last few weeks, the Keystone Kops have taken over the Republican presidential caucuses. First Mitt Romney was declared the winner of the Iowa caucuses by a scant eight votes, and then Republican Party officials in Iowa said that there were so many local reporting problems that a winner could not be declared even though Rick Santorum was 34 votes ahead. Oops, they declared Santorum the winner anyway. In Nevada, Republican officials decided to hold a special late-night session of their Saturday caucus to accommodate Orthodox Jews and Seventh-day Adventists. This caused an uproar when Ron Paul supporters objected to requiring the late-comers to sign a statement that their religious obligations prevented earlier attendance, saying that people who had to work during the day should have the right to vote at the late-night caucus, too. Adding to the tumult, it took election officials in one Nevada county an extra day to count a small number of votes and deal with a “trouble box” of disputed ballots. Now comes news from Maine that Mitt Romney may not have won the Maine caucuses by 200 votes as initially reported, because some ballots have gone uncounted.

All of this is an embarrassment for the GOP, but it’s not a Republican problem. Four years ago, I wrote a Slate column describing the problems with the Democratic caucuses as Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama battled for their party’s nomination: That time around, in the Iowa caucuses voters had no right to cast a secret ballot; and in the Nevada caucuses rural votes counted more than urban ones. Hillary Clinton got more popular votes in the state than Barack Obama did, but got 12 delegates to Obama’s 13. Then came Texas-sixed problems with that state’s hybrid primary-caucus: long lines, unclear rules, the tailing of an election official to a police station when she took home caucus sign-in sheets to “correct” them, and even reports of three physical confrontations at Dallas caucus sites. Clinton got more votes in the primary, but Obama got more delegates because he got more votes in the caucuses.

None of this should actually be a surprise. This country has a hard enough time with competently run elections when professional election administrators are in charge. Caucuses are run by political party volunteers once every four years, without the normal safeguards (for example, while the GOP has supported voter identification laws, they were not required for the Republican Party caucuses). Without adequate procedures for ensuring that votes are properly cast, counted, and audited, a drumbeat of mistakes is inevitable.

Caucuses hark back to an earlier era, when they were a way for the parties to organize and provided a space for small-scale deliberations about which candidate deserved support. A deliberative process seemed especially appropriate in Iowa, where voters get to see the candidates up close and serve as proxies (supposedly) for the rest of us.

But none of these rationales any longer make sense. Parties organize more effectively through conventions, voter registration drives, and get-out-the-vote efforts than by serving as amateur vote-counters twice a decade. Caucuses are now a place for aggregating votes, not for real deliberation. Mostly people just come and vote. In fact NPR’s Bryan Naylor reports that Iowa would like to use voting machines in the next round of caucuses—it’s just that they’re worried that New Hampshire, with its first-in-the-nation primary, will squawk.

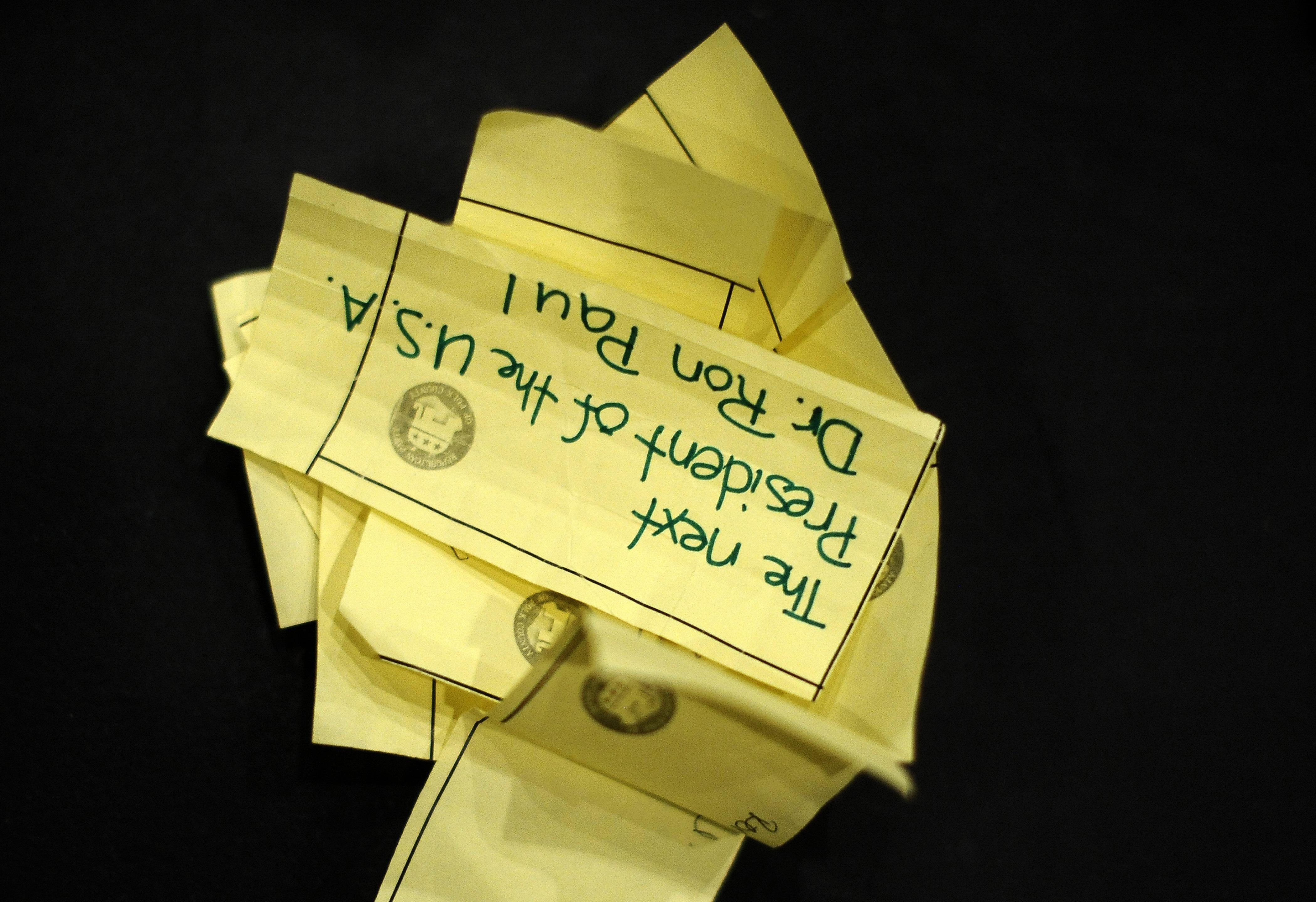

Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images.

Turnout in caucuses can be abysmally low. Fewer than 40,000 people voted in the 2012 Nevada Republican caucus. Compare that to the 412,000 voters who voted for John McCain in the 2008 general election in Nevada. Maine’s caucus turnout last week was only about 3 percent, according to the Washington Post, “Out of 6,755 registered Republican voters, 223 showed up to vote in Portland.” Since you have to hang around to vote, busy people don’t show up and many members of the military are disenfranchised.

Finally, caucuses make less sense now that campaigns for president have become more national in scope, and voter preferences about candidates shaped less by living room chats and more by negative ads run by a candidate’s shadow super PAC. As campaigns become less retail, there’s no reason to burden voters who want to help choose a presidential nominee with the extra demands of a caucus.

How to get rid of the caucuses? For reasons I’ve explained, I don’t expect the Supreme Court to step in and rule the caucus process unconstitutional. Parties don’t have to use a one-person, one-vote rule to choose their nominees, and they could probably get away with just about anything short of race discrimination in running their nomination processes. As Justice Antonin Scalia recently wrote for a seven-justice Supreme Court majority, “A political party has a First Amendment right to limit is membership as it wishes, and to choose a candidate-selection process that will in its view produce the nominee who best represents its political platform.”

But the Supreme Court also has said “it is too plain for argument” that states can require parties to use primaries or conventions rather than caucuses or smoke-filled rooms to pick nominees who appear on the general election ballot. And Congress might be able to go further. An important article by Justice Scalia, written before he took the bench, bolsters the case that the Constitution gives Congress has the power to regulate aspects of the presidential nominations process.

Congress should take the court up on its offer and scrap the caucuses. And while they’re at it, how about taking away Iowa and New Hampshire’s status as first in the nation in choosing the president as well? There have been a number of fairer proposals, such as a series of rotating regional presidential primaries, giving each part of the country its turn to go first. Iowa and New Hampshire won’t go down without a fight. But there is no reason these two states should always get millions of dollars worth of extra attention from presidential candidates.

Amateur hour is over. The choice of a president is simply too important to put in the hands of party bumblers and the small percentage of people who are willing to spend hours to cast a vote. Let’s have primaries—and then figure out how to make sure all those voting machines work properly.