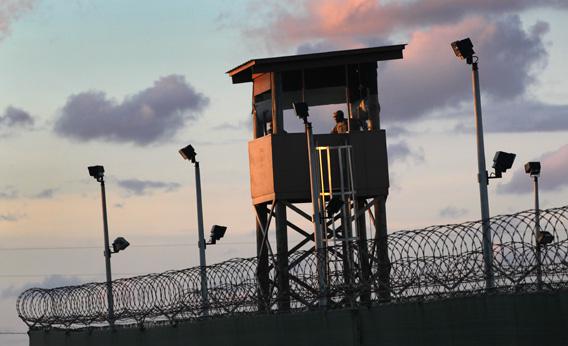

Ten years ago today, George W. Bush’s first 20 prisoners arrived at the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba. They were, we were promised at the time, “the worst of the worst.” Eventually the camp came to house almost 800 prisoners, of whom 171 still remain. Some of them were tortured, some may be tried by military commission, and some have died or will die there. The 10-year anniversary was marked today by protests, articles, editorials, letters, personal remembrances, and reminders that Guantanamo itself is only part of the problem with Guantanamo.

In the foreign press they are saying that the camp “weighs heavily on America’s conscience” and that “the shame of Guantanamo remains.” But most Americans are experiencing the anniversary without much conscience or shame; just with the same sense of inevitability and invisibility that has pervaded the entire 10-year existence of the camp itself: inevitability in that we somehow believe the camp was truly necessary and nobody ever really expects the conflict to be resolved; and invisibility in that nobody really knows what’s happening there, or why.

So while the rest of the world experiences this day in terms of how the United States ever got itself into this situation and what it’s all done to America’s reputation abroad, here in the United States the discourse is confined to how we will continue to live with it and why. The paradox of Guantanamo has always been that it’s been invisible to so many Americans, and yet the only thing the rest of the world sees. The whole point of the prison camp there was to create a legal black hole. We’ve fished our wish: The world sees only blackness; we see only a hole.

That’s always been the challenge of Guantanamo: making it seem real to Americans who have tended to think of the Cuban camp as the potted palm in the war on terror. And it’s very difficult to get exercised over a potted palm.

From the perspective of a legal journalist, the real tragedy of this anniversary lies not in all the waste, and error, and gratuitous suffering. The tragedy even transcends the politics and the posturing and the will of the people to do nothing beyond shrugging that, well, mistakes were made. The real tragedy is that when the president and Congress failed to understand what had happened at Guantanamo Bay, the courts stepped in. The Supreme Court’s 2008 ruling in Boumediene, holding that the prisoners at Guantanamo who were not American citizens still had the right of habeas corpus, represented the court doing precisely what it was built to do: remind the will of the people that sometimes it is full of shit.

But since Boumediene, the court has taken itself out of the shining beacon of justice business and left the administration of those habeas corpus proceedings to the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. That court has systematically thrown the whole habeas process through a wood chipper until it’s not clear that there is anything left of the promise of Boumediene, beyond a command that some prisoners are due some due process to be named by someone sometime later.

This fact was noted in a dissent by Judge David Tatel in a recently declassified decision regarding a Guantanamo detainee, Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif. Latif is a citizen of Yemen who has been held at Guantanamo since 2002. In October the three-judge appellate panel ruled 2-1 that a district court had erred in ordering Latif’s release from the prison. There is much that is worrisome about the majority ruling in Latif, which Adam Liptak described recently as the “next great Guantánamo case—whether the Supreme Court agrees to hear it or not.”

As Liptak wrote: “If the justices agree to hear the Latif case, they can explain whether their Guantánamo decisions were theoretical tussles about the scope of executive power fit for a law school seminar or whether they were meant to have practical consequences for actual prisoners. If the Supreme Court turns down the case, it will be signaling that it has given up on Guantánamo.”

But in the spirit of the day, I urge you to stop for a moment and look at the decision itself, so heavily redacted that page after page is blacked out completely. The court, in evaluating a secret report on Latif, can tell us very little about the report and thus the whole opinion becomes an exercise in advanced Kafka: The dissent, for instance notes that “As this court acknowledges, “the [district] court cited problems with the report itself including [REDACTED]. … And according to the report there is too high a [REDACTED] in the report for it to have resulted from [REDACTED].” Liptak describes all this as an exercise in “Mad Libs, Gitmo Edition.” But in the end, it’s also an exercise in turning the legal process of assessing the claims of these prisoners at Guantanamo Bay into something that replaces one legal black hole with another: pages and pages of black lines that obscure in words what has been obscured in fact. Americans will never know or care what was done at the camp and why if the legal process that might have transparently corrected errors happens behind blacked-out pages.

It’s hard to say anything new about 10 full years of Guantanamo, beyond the fact that most of what we wrote two, four, and seven years ago still holds mostly true. But given that Americans have an increasingly hard time thinking about the camp, and the rest of the world can think about little else, perhaps we can agree that pretending it isn’t there probably isn’t the answer.