A “single witness” linked Juan Smith to the five murders for which he was convicted in New Orleans in 1995. The Supreme Court reversed Smith’s conviction yesterday, dwelling on that single witness in the 8-1 opinion it handed down. The justices had been “incredulous” at oral arguments at the conduct of New Orleans prosecutors. So it was an easy case, decided early in the season, with seven justices joining Chief Justice Roberts’ short and sweet three-and-a-half page opinion. But sometimes it is the easy decision that disguises insidious problems. The head prosecutor in New Orleans at the time, Harry Connick Sr., was nowhere to be found in the court’s opinion.

Before we get to him however, it is noteworthy that the court nowhere called the single witness who identified the culprit in this case the “single eyewitness.” Was he even really an eyewitness? At trial, the witness said he saw the attacker face to face and was sure Smith was the one. He said he had “[n]o doubt.” That sure sounds like the testimony of an eyewitness.

Everything in this case hinged on that single witness. The police explained that “[a]s amazing as it may seem,” no fingerprints matching Smith were found. And jurors place great stock in the testimony of a confident eyewitness. This was a terrible mass murder, where men stormed into an apartment, demanded money and marijuana, told everyone inside to lie on the floor, then shot five people. Smith was sentenced to life without parole.

The problems in the case emerged only during state habeas proceedings. That’s when Smith obtained for the first time notes from the detective stating that the eyewitness said on the night of the murder that he “could not … supply a description of the perpetrators other then [sic] they were black males.” Again, five days after the crime, the ostensible eyewitness said he “could not ID anyone because [he] couldn’t see faces” and “would not know them if [he] saw them.” The detective wrote these statements down—and then wrote down “Could not ID.” It’s understandable that the eyewitness was, as he later said, “too scared to look at anybody” under the circumstances. But usually police know that a person who didn’t see a face is not an eyewitness at all.

It’s a big risk to even show an eyewitness like that a lineup. But New Orleans police were undeterred. In fact, they showed 14 separate photo arrays to another witness, who said she could not identify anyone. That didn’t stop these police from trying over and over again. They didn’t succeed with her, but they also showed 14 separate photo arrays to the “single witness.” Months after the crime, they finally succeeded in getting him to identify Smith. How did this happen? Smith’s briefs describe how the New Orleans Times-Picayune ran a story naming Smith as a suspect, including a photo. After seeing that newspaper story, all of a sudden the single witness became the single eyewitness.

It was easy for the Supreme Court to decide that such powerful evidence undermining the testimony of the state’s only evidence was “material” and that there was a “reasonable probability” that it would have made a difference at trial and that the conviction needed to be reversed (the standard under Brady v. Maryland, which entitles the defense to have such exculpatory evidence). It was, said eight justices, serious misconduct to hide such evidence. All the jury heard about was the photo array, four months after the crime, when the eyewitness first identified Smith, and then they saw him at trial, testifying with absolute confidence.

The Supreme Court cited its 1995 decision in Kyles v. Whitley, which like Juan Smith’s case was another New Orleans case prosecuted by Harry Connick Sr.’s office. In Kyles, a whole pile of evidence was concealed, undermining the testimony of a slew of witnesses (a wonderful book about the case, Desire Street, describes even more police and prosecutorial misconduct). In Juan Smith’s, more than just the statements by the single witness were withheld from his defense. Other exculpatory evidence not turned over included forensics relating to the firearms analysis (indicating that ammunition at the scene did not match the type of gun that the single witness said Smith supposedly carried), evidence pointing to other possible suspects, and more contradictory statements.

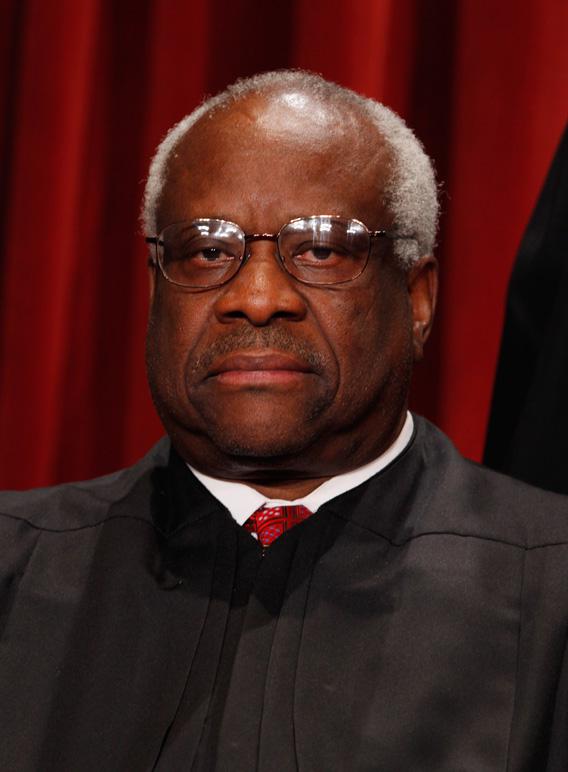

And so the court’s opinion was short. But then Justice Thomas wrote a long, long (17-page) dissent. Recall from last term how tolerant the justice is of prosecutorial misconduct coming out of Harry Connick’s office. More on that to come. But what might elude you on first reading is that here Justice Thomas calls the witness “the eyewitness.” Justice Thomas argues that the revelations about this witness would not likely have made a difference at trial, even if they could have been given “some weight.” Justice Thomas emphasizes how, even months after the crime, the eyewitness saw Smith’s photo and said, “This is it. I’ll never forget that face.” The witness had described the perpetrator as having gold teeth, which Smith did have (although apparently several other suspects did as well).

Justice Thomas details why he concluded that the witness “evince[d] a discriminating, careful eye over a 4-month investigative period.” This was a model and “confident” eyewitness—moreover, one who was extensively cross-examined at trial. This witness was tested in the fires of the crucible of the courtroom and the jury convicted. What more could the justices demand?

This analysis indicates little familiarity with the vast body of research on eyewitness memory. We know, for instance, that the memory of an eyewitness degrades—in a matter of hours, not days. If this eyewitness knew he could not identify the attacker on the day of, or in the days after the crime, nothing that happened in the weeks and months that came later could somehow improve a rapidly vanishing memory. Nor does the confidence of an eyewitness at trial mean much at all as to its accuracy. (Jurors—and judges—put a lot of misplaced stock in confidence of witnesses.)

In my own research reading the trials of the first 250 people exonerated by DNA tests, I saw countless examples of eyewitnesses who were certain at trial and claimed they would never forget that face—but subsequent DNA tests showed they were wrong. Most cases, like the murders in Smith v Cain, do not involve any DNA that can be tested at the crime scene. That is why it is so important that police proceed with caution. Police know to take careful notes when a person says he is pretty sure he cannot identify anyone. They know they may not have an eyewitness at all. They know they had better investigate and try to find other evidence, rather than risk a lineup. That shaky or non-eyewitness may easily pick out a lineup “filler” and damage his credibility. Eyewitnesses generally pick out fillers as much as one-third of the time. Worse, the eyewitness may pick out an innocent man. For these reasons it is important for police to use careful procedures to document and test the memory of an eyewitness.

Good police officers know all that, but do prosecutors? If prosecutors hide their investigative work from the defense, there can be no end to the miscarriage of justice. What Chief Justice Roberts did not mention in his opinion yesterday was that this was not the first time the justices had heard of persistent failures of Harry Connick Sr.’s district attorney’s office to turn over obviously important evidence to the defense. In Connick v. Thompson, Justice Thomas authored the majority opinion in which the Supreme Court blithely threw out a multimillion dollar verdict in favor of an exonerated man who also had forensic evidence concealed from him by the prosecution. Justice Ginsburg in her dissent noted Connick’s “cavalier approach” to Brady v. Maryland and a “culture of inattention” to such misconduct.

The court’s decision in Connick powerfully undermined incentives for prosecutors to carefully supervise to ensure that information is not concealed from the defense and from the courts. Meanwhile, we keep hearing of revelations regarding police and prosecutorial misconduct: entire crime labs shut down because forensics are botched or concealed, high-profile prosecutions derailed and exonerations because of police or prosecution misconduct.

In the face of rulings immunizing prosecutors and their superiors from consequences of misconduct, what impact will yesterday’s perfectly correct but one-off decision have? Not much. Unless police do lineups right in the first instance, carefully document evidence, and prosecutors disclose full evidence to the defense, we will hear no end of eyewitness errors and prosecutorial misconduct throwing convictions into doubt. The prosecutor plays a “special role … in the search for truth in criminal trials,” the court said in Strickler v. Green. Let’s hope that the court does more to make sure that “special” is not just a euphemism, but actually means having a great responsibility to ensure “that justice shall be done.”