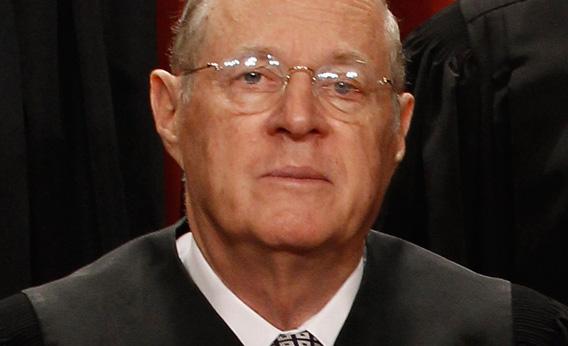

Soft money is coming back to national politics, and in a big way. And we can blame it all on a single sentence in Justice Anthony Kennedy’s opinion in 2010’s controversial Citizens United decision—a sentence that was unnecessary to resolve the case.

In this election cycle, “superPACs” will likely replace political parties as a conduit for large, often secret contributions, allowing an end run around the $2,500 individual contribution limit and the bar on corporate and labor contributions to federal candidates.* To understand how we got into this predicament, we need to go back briefly to the 1970s. In the wake of Watergate and other money-in-politics scandals, Congress imposed tough new campaign finance restrictions. Not only did the law limit contributions to federal candidates to $1,000 per person (an amount it eventually raised to $2,000 and indexed to inflation), it also limited independent spending—that is, no one person or group could spend more than that amount—to $1,000. In a Solomonic 1976 decision, the Supreme Court in Buckley v. Valeo split the baby, upholding the contribution limits but striking down the independent spending limit as a violation of the First Amendment protections of free speech and association.

Buckley set the main parameters for judging the constitutionality of campaign finance restrictions for a generation. Contribution limits imposed only a marginal restriction on speech, because the most important thing about a contribution is the symbolic act of contributing, not the amount. Further, contribution limits could advance the government’s interest in preventing corruption or the appearance of corruption. The court upheld Congress’ new contribution limits.

It was a different story with spending limits, which the court said were a direct restriction on speech going to the core of the First Amendment. Finding no evidence in the record then that independent spending could corrupt candidates, the court applied a tough “strict scrutiny” standard of review and struck down the limits. (In a footnote two years later, however, the court left open the question of whether corporate independent spending could corrupt candidates.)

Fast forward a few decades. In Citizens United, Kennedy resolved what appeared to be an empirical question about independent spending and corruption: “We now conclude that independent expenditures, including those made by corporations, do not give rise to corruption or the appearance of corruption.”

The flat statement of fact is illogical. If the court believes that the government may limit a $3,000 contribution to a candidate because of its corruptive potential, how could it not believe that the government has a similar anticorruption interest in limiting $3 million spent in an independent effort to elect that candidate? Would a federal candidate not feel much more beholden to the big spender than the more modest contributor?

It is not even clear that a majority of the court (or even Kennedy) actually believes this sentence. The Citizens United decision is at odds with Kennedy’s opinion from just six months earlier in Caperton v. Massey, recognizing that a $3 million contribution to an independent group supporting the election of a West Virginia supreme court justice required that the justice recuse himself from a case involving the independent spender supporting his candidacy. The Caperton Court pointed to the “disproportionate” influence of that spending on the race and at least an appearance of impropriety.

It gets even worse: That sentence from the Citizens United case is unnecessary. If the court wanted to strike down the corporate spending ban, it could have simply said that even assuming independent spending has the potential to corrupt, an absolute corporate spending limit, like the individual spending limit struck down in Buckley, imposed too high a free speech cost and therefore violates the First Amendment.

But the court’s declaration that independent spending does not corrupt has spawned the Super-PAC and the unraveling of campaign finance law. The unraveling went like this. First, if independent spending cannot corrupt, then an individual’s contributions to an independent group cannot corrupt. (Gone was the $5,000 contribution limit to political action committees—or PACs—which only spend independently to support or oppose federal candidates.) Second, if an individual’s contributions to one of these “Super-PACs” cannot corrupt, then neither can a corporation’s or a labor union’s. (Corporations now have a way to influence elections anonymously, thus avoiding the risk of alienating customers.) Third, if an individual has a constitutional right both to contribute to a candidate and to spend independently, then a PAC should be able to do the same thing simply by having two bank accounts. (Every PAC is now a Super-PAC.)

All of this has spawned a shadow campaign in which each presidential candidate has his or her own supportive Super-PACs, and contributors can curry favor with the candidates by giving unlimited sums to the Super-PACs. Even worse, thanks to holes in our disclosure laws, it is possible to use other organizations as money launderers to keep Super-PAC contributions’ ultimate sources secret from the public. And Super-PACs like American Crossroads may have found a way to make ads with the candidates themselves without losing their label as “independent” spenders.

Now comes the most audacious argument in this series so far. If all PACs are Super-PACs, then the rules for these PACs should also apply to “leadership PACs.” Leadership PACs are political committees that sitting members of Congress (and others) set up to allow them to make contributions to other candidates and spend money to support their election. It is a way for a member of Congress to build influence.

Sen. Mike Lee’s Leadership PAC, the Constitutional Conservatives Fund PAC, has just asked the Federal Election Commission for permission to collect unlimited contributions from corporations, labor unions, and wealthy individuals for independent spending to elect other candidates. The SuperPAC’s lawyers argue that there’s no danger of corrupting these other candidates, because its spending to help them get elected will be independent of those candidates.

Even if we suspend disbelief and agree on this point, the request ignores the greater danger: that the leader of the leadership PAC will become, or appear, corrupt. Corporations or labor unions (acting through other organizations to shield their identity from public view) could give unlimited sums to an elected official’s leadership PAC, which could then be used for the official to yield influence with others.

There’s nothing to stop someone like Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell from effectively becoming the fundraising arm of the Republican Party, funneling all the money through his leadership PAC. The McCain-Feingold law barred political parties from collecting such unlimited “soft money” contributions, and the Supreme Court in 2003 upheld that limit on the grounds that such unlimited fundraising by politicians could corrupt politicians or create the appearance of corruption.

The Supreme Court in Citizens United did not touch that holding, and said it was doing nothing to mess with the contribution rules. But Kennedy’s unfortunate sentence—which denies the reality that large independent spending favoring a candidate can sometimes corrupt or create the appearance of corruption—looks like it may doom those soft-money rules too. The result of all this is that federal campaign finance law is unraveling even faster than pessimists expected after Citizens United.

John Adams famously said that “facts are stubborn things.” But Anthony Kennedy foreclosed a look at the facts. By resolving a question of fact by judicial fiat, he may have sealed the fate of our campaign finance system.

Correction, Oct. 25, 2011: This article originally misstated the individual contribution limit for federal candidates. It is $2,500, not $2,400. (Return to corrected sentence.)