The much-whispered hope of liberals and much-shouted anxiety of conservatives is that John Roberts, once robed, will be sucked up into the mystical, nameless force that pulls Supreme Court justices leftward. The tendency of justices to “defect,” or “evolve” (circle the word you prefer) to the left during their careers on the high court is legendary. Political guru Larry Sabato estimates that as many as a “quarter of confirmed nominees in the last half-century, end up evolving from conservative to moderate or liberal.” The burning question about Roberts then is not, “What does he really believe?” so much as, “How long will he really believe it?”

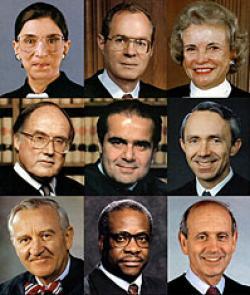

Clarence Thomas is said to have bragged: “I am not evolving” following his confirmation, and he’s proved true to his word. But tales of other rock-ribbed Republicans listing leftward abound. Consider the twin disappointments of President Eisenhower’s administration: William Brennan—who went on to become the moral and intellectual leader of the court’s liberal faction, and Chief Justice Earl Warren—an appointment Eisenhower later characterized as “the biggest damn fool mistake I ever made.” Consider Harry Blackmun—the Nixon appointee who went on to author Roe v. Wade, and Lewis Powell, savior of affirmative action, whom Nixon also appointed. Consider John Paul Stevens (a Ford appointee), Sandra Day O’Connor (a Reagan appointee), Anthony Kennedy (ditto), and David Souter (Bush I). All presented as predictable conservatives until they hit the bench. Yes, there are a few defections in the opposite direction: FDR appointee Felix Frankfurter and Kennedy appointee Byron “Whizzer” White became more conservative on the court. But no one really disputes that the trend is largely from the right to the left. The question is, why?

Half-baked theories about the drift to the left abound. Here they are, for Roberts’ watchers to consider:

1.The Greenhouse Effect “The Greenhouse Effect” is the name of a phenomenon popularized by D.C. Appeals Court Judge Laurence Silberman referring to federal judges whose rulings are guided solely by their need for adulation from legal reporters such as Linda Greenhouse of the New York Times.The idea is that once confirmed, justices become desperate to be invited to the right cocktail parties and conform their views to those of the liberal intelligentsia. Robert Bork recently told the New York Times, “It’s hard to pick the right people in the sense of those who won’t change, because there aren’t that many of them. … So you tend to get people who are wishy-washy, or who are unknown, and those people tend to drift to the left in response to elite opinion.” Similarly, Max Boot argues that Anthony Kennedy “is no Warren or Brennan, to be sure, but whenever he has a chance to show the cognoscenti that he’s a sensitive guy—not like that meany Scalia—Justice Kennedy will grab at it.”

The problem with this theory is that it accepts a great conservative fiction: that there is vast, hegemonic liberal control over the media and academia. This may have been somewhat true once, but it’s patently untrue today. Jurists desperate for sweet media love can hop into bed with the Limbaugh/Coulter/FOX News crowd. Clarence Thomas has made a career of it. There is a significant and powerful conservative presence in the media, inside the Beltway, and in academia. And my own guess is that Federalist cocktail parties in D.C. are vastly more fun than their no-smoking/vegan/no-topless-dancing counterparts on the left.

A correlate of the “Greenhouse Effect” is that justices tend to grow obstinate in response to partisan criticism. As Greenhouse herself points out in her recent biography, Becoming Justice Blackmun, the justice reacted so strongly to the tsunamis of hate mail and media vilification following Roe that he became more liberal in other areas as a result. Perhaps Anthony Kennedy now takes some of his more lefty positions precisely because of the conservative calls for his impeachment following his votes in key abortion and gay rights cases.

To be sure, no judge likes to look stupid in the papers, and every justice keeps at least one eye on the history books. But it’s too simple-minded to assert that judges reinvent themselves each morning to please the New York Times or the cafeteria at Harvard Law School.

2. Mean ol’ Nino This theory holds generally that justices tweak their philosophies and ideologies in response to each other; and specifically, that Antonin Scalia and (to a lesser degree) Clarence Thomas have managed to drive once stalwart conservatives into the arms of the court’s lefties. Mark Tushnet, a law professor at Georgetown University, argues that the failure of the Rehnquist Court to achieve the expected rollback of the social revolution spawned by the Warren Court has a good deal to do with Antonin Scalia’s failure to lead the court’s moderate conservatives. Tushnet suggests in a recent law-review article that Scalia’s “acerbic comments on his colleagues’ work,” and his general tendency to run with constitutional scissors, ultimately drove both O’Connor and Kennedy to form alliances with the court’s liberals, particularly David Souter and Stephen Breyer.

3.“Seeing the Light” This theory, a favorite of liberals, hinges on the claim that jurists eventually drift leftward because they become increasingly compassionate/sensitive/wise with age, and that each of these values is a fundamentally liberal one. In last week’s Chicago Tribune, Geoffrey R. Stone, a professor of law at the University of Chicago, editorialized that “[j]ustices are continually exposed to the injustices that exist in American society and to the effects of those injustices on real people. As they come more fully to understand these realities, and as they come to an ever-deeper appreciation of the unique role of the Supreme Court in our constitutional system, they become better, more compassionate justices.”

The problem with this notion—that judges begin to appreciate the intrinsic rightness of tolerance, pluralism, and acceptance—is that it flies in the face of a basic human truth: We almost all become more conservative with age. This theory also fails to explain why some jurists—notably Scalia and Thomas and, to a great extent, Rehnquist—fail to budge from their ideological positions over the years. While it may feel good for liberals to assert that the drift to the left is simply a sign of wisdom, it strikes me as too simple and self-serving to be accurate.

4.The Boys in the Bubble This is the theory used to explain David Souter’s dramatic defection from solid conservative preconfirmation to reliable liberal justice. The argument is that he had so little “real-life” experience prior to his confirmation that he only developed his jurisprudential views after donning the black robe. Souter himself has said that when he was confirmed he knew next to nothing about important federal constitutional issues—having had experience as a state attorney general and then as a state supreme court justice. At his confirmation hearings he answered truthfully but saw his views change radically once he began to truly study the issues. Because judges often hail from Ivy League institutions or from the lower courts, they may be less likely to have fully formed political ideologies. Certainly there is some truth to the proposition that justices who either rose through the executive branch (like a Clarence Thomas) or had tremendous advocacy experience (like a Ruth Bader Ginsburg) are less likely to change their views once confirmed.

5.The Law Is a Moderate Mistress This theory holds that there is something inherently moderating about the law itself; that the traditions and pace of the legal system tend to foster centrism and moderation. The “drifters” of the Supreme Court world—the Kennedys and O’Connors—are not so much evolving toward the left, therefore, as they are evolving toward the center.

This theory explains why Stephen Breyer has similarly moved rightward, proving to be the swing vote in this term’s blockbuster case allowing displays of the Ten Commandments on state grounds, and joining the court’s conservatives in matters as vital as the presidential power to detain enemies in wartime. We don’t hear much from the media about Breyer’s occasional defections to the conservative team, and certainly liberal pundits don’t call for his impeachment the way Phyllis Schlafly does each time Justice Kennedy strays from the reservation. But it remains true that strong centripetal forces on the court tend to pull everyone slightly toward the middle. *

What does all this say about the likelihood of a John Roberts “evolution” to the left? Rank speculation suggests that he may drift somewhat, but not a whole lot. Roberts’ intellectual confidence points to a man unlikely to be swayed by the siren song of the opinion pages, and his ability to get along with everyone suggests that he may not only withstand Scalia’s barbs but could assume the role of leader of the conservative wing—attracting moderates like Kennedy and Breyer back to the fold. Roberts’ extensive experience in the executive branch and his role as successful advocate for conservative positions means he likely has a well-thought-out judicial philosophy on hot-button issues like abortion and gay marriage, and that, unlike Souter or O’Connor, he won’t be crafting his views as he goes. Roberts is also a deeply religious man, which may keep him from sliding toward the center the way Scalia and Thomas have resisted the pull.

But, unlike Scalia and Thomas, Roberts seems to recognize the fundamental role and value of moderation in the law. He respects its glacial pace and tends to understand that his job is to guide, not shape, the law. In short, Roberts may shift toward the middle over time, but he is highly unlikely to become the court’s staunchest liberal. However, 30 years is a long time. And Linda Greenhouse is most charming.

* Correction, August 5, 2005: The original piece suggested that centrifugal force pulls objects toward the center. The correct word should have been centripetal force, which in fact pulls objects toward the center. Click here to return to the corrected sentence.