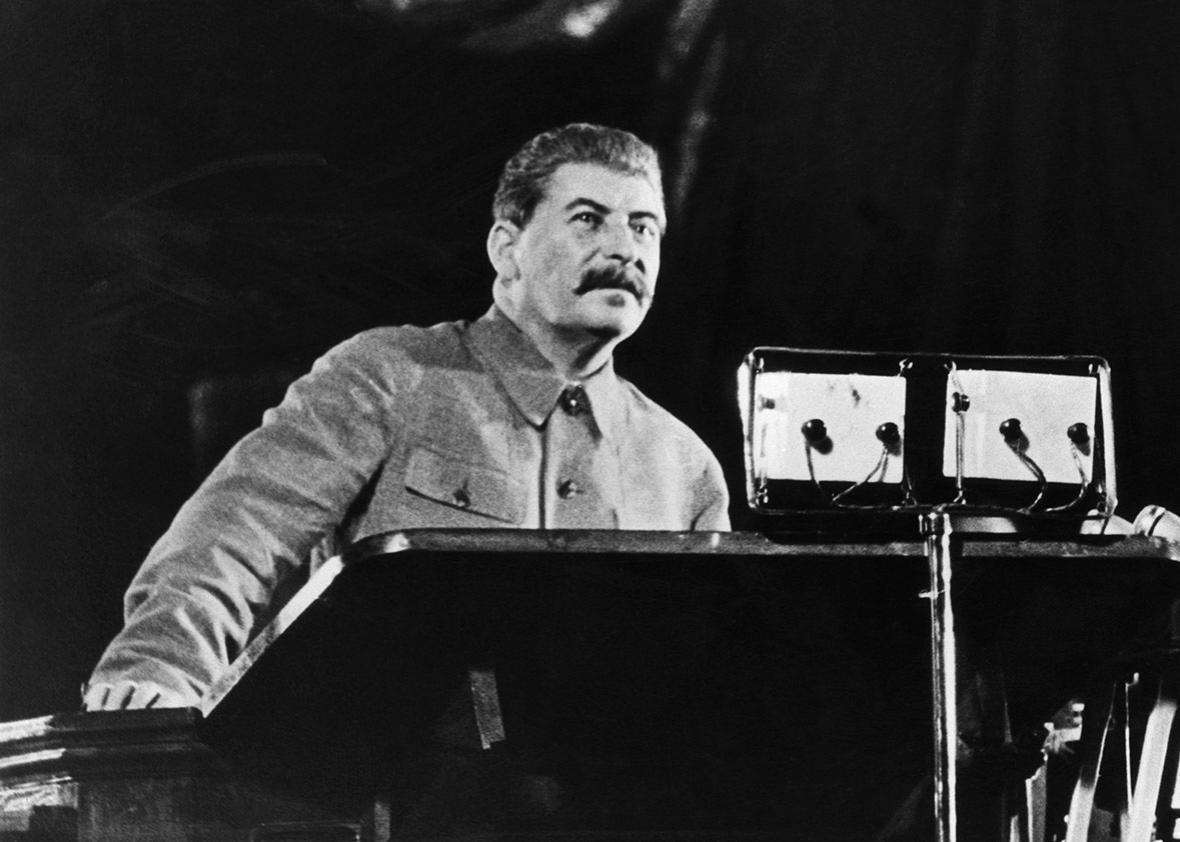

On this week’s episode of my podcast, I Have to Ask, I spoke with Stephen Kotkin, a historian of Russia and the Soviet Union who has just published the massive second volume of his Joseph Stalin biography, called Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929–1941. With another volume set to come, this one ends just on the eve of Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union.

Below is an edited excerpt from the show. In it, we discuss what people misunderstand about Stalin’s psychology, why he launched the purges in the manner he did, and the ways in which he differed from Adolf Hitler.

You can find links to every episode here; the entire audio interview is below. Please subscribe to I Have to Ask wherever you get your podcasts.

Isaac Chotiner: Why did you decide to embark on this massive 2,000-page, two-volume biography of Stalin? What did you feel like had not been said about Stalin?

Stephen Kotkin: Maybe I was crazy?

I wasn’t going to say it, but yeah.

I’m in Soviet history, and it’s one of these occupational hazards that after someone does some work on this and that, the Stalin temptation arises. Some people indulge it, and some don’t. What happened was, in the very late ‘90s, Stalin’s personal archive was released. This was about 1999–2000, and I had been thinking about whether the regime and his personal rule could be studied with the kind of depth that I applied to the single town that I wrote a book about previously.

It seems like you were resistant to the pop-psychological explanations of why Stalin became the man he became.

We have this fantastic phenomenon—Stalin, Mao [Zedong], Pol Pot. You begin to see a pattern here. You begin to see a kind of ruler, a type of rule, a way of going about tyranny, despotism, whatever you want to call it. Is it really personal, or how personal might it be? How do we study a phenomenon that seems to keep repeating itself? Clearly, there’s something not just in the person—the person matters a great deal—but there’s something bigger than that. And so we want to figure out the largest structures, the combination of ideas and institutions and politics that not only make possible a figure like Stalin but actually make it pretty likely. Certain systems bring about certain types of personalities, or at least they bring them to the fore.

What was it about the environment that Stalin was in that may have made someone like him more likely?

Here we have a guy who’s born into a poor family on the periphery of the Russian Empire, not someone who’s destined for the kind of role that he would later create for himself.

His father’s a cobbler. His mother’s a seamstress. He goes to school. He does well at school. He gets Russified because it’s the Russian Orthodox Church that builds the schools in Georgia on the southern periphery of the Russian Empire. If you looked at this life all the way through 1917, when Stalin would be 39 years old, you don’t see the future Stalin yet.

Some say his father beat him. Well, I got to tell you, my father beat me, too, and I haven’t killed 20 million people yet.

Still time, but yeah.

There’s maybe potential, you might say, but it looks unlikely in my case, right? So I decided to look at what people thought about him in real time—that is to say, not retrospectively. Thirty years later, if they survive, they remember when he was on the schoolyard when they were teenagers and he said, “Oh, I’m going to get you all.” So they predict that he’s going to kill 20 million people, somehow, later on. Well, that’s not the answer.

The answer has to do with Russian power in the world, this very difficult place, and its aspirations to be a great or the greatest power or providential power under God has to do with Bolshevik ideology and trying to build a new world that’s anti-capitalist.

There’s obviously this large debate about whether Stalin is sort of a continuation of the Russian revolution or a break, where the Russian revolution went wrong, and it seems like one of the points you want to make is the degree to which Stalinist behavior was actually brought about by Bolshevik ideology.

Lenin in 1917 called his action a coup. Lenin called his new regime a dictatorship. Lenin said, “We’re going to eliminate whole classes of people,” which he called the bourgeoisie, as well as the gentry and all that. Lenin said of all this, and he began to do this. So the idea that there was some kind of revolution in there, which was better than Stalin, is hard to square with the documents.

But that’s not the important point. The important point is building a dictatorship is really hard. It’s not something that anybody can do. It takes talent and perseverance, of course in a perverse way, but nonetheless we have to give Stalin credit, perverse credit, for this incredible achievement of building a dictatorship inside the dictatorship of Lenin’s revolution. So, that’s a big story. The story is not whether Stalin fulfills the revolution and usurps power from Lenin. The story is the incredible dictatorship that he produces.

But it seems like your book constantly highlights ways in which, even if that’s the case, that Stalin’s behavior did matter every single day, and he took huge decisions that another leader may not have taken.

The normal idea of an alternative to Stalin, as you alluded to, is a kind of social democratic pluralistic revolution in the 1920s, sometimes called the Bukharin alternative, sometimes imagined or fantasized as a social democracy. The alternative to Stalin was collapse of the regime. In other words, it took somebody like Stalin to consolidate this dictatorship and implement the Bolshevik ideology, the Marxism-Leninism.

Let’s think about 1928, which is where Volume 1 ends. One percent of the arable land in the country is collectively worked. So you’ve got a Bolshevik urban revolution, which is avowedly anti-capitalist, eliminating the bourgeoisie and creating state-owned and state-managed industry. You have a parallel separate peasant revolution where the peasants eliminate the gentry class and seize the land and become de facto landowners.

And Stalin looks at this and he says, “We can’t have this.” This is socialism in the cities and capitalism in the countryside. And any Marxist will tell you that class determines the political system, social relations of production determine the political system, so as the Marxists around Stalin also believed, this was not permanently stable. The thing that he did, which they couldn’t understand or couldn’t believe he could do, was to forcibly collectivize the entire Eurasia, more than 120 million peasants either deported internally or forced into collective farms. And he did this despite the fact that there was massive famine, despite tremendous opposition that arose, mass peasant resistance, and he did this because he was a true believer in the socialist future.

How does your analysis of the famine differ from other historians’?

We have very good documentation on what happened during the famine between 1931 and 1933 bleeding into 1934, a little bit, between 5 million–7 million people starved to death or died of related diseases. That’s a pretty horrific famine. Another 50 million–70 million people starved and survived. Much of the literature wants to make this an intentional famine. Stalin intended, by this count, to kill these peasants—especially because many were Ukrainian, and he supposedly committed a genocide against the Ukrainian nation.

So we have documentation of Stalin’s intentional murders that could completely overwhelm this studio, if it was all stacked up. We have hundreds of execution lists that he signed, hundreds, thousands of orders where he ordered torture or murder of individuals. So why don’t we have that for the famine? In other words, if Stalin wanted to clean up his regime and eliminate documents showing him in an ill light, he failed, because those documents are in abundance, and for the famine we don’t have such a document.

Let’s turn to the purges and the executions, which are set off in 1934 when there is a murder of a man named Kirov, who is a party member, and this was kind of what Stalin used as a pretext to begin the purges. There’s been a long historical debate about whether Stalin himself had Kirov murdered as an excuse to do this, sort of like the Reichstag fire in Germany.

So once again, we’re dealing with well-trod mythologies about Stalin: that he was a mediocrity, he was a usurper, he destroyed rather than fulfilled the revolution, he intentionally killed the peasants and intentionally tried to commit genocide against the Ukrainian nation. And, of course, that he murdered Kirov in order to begin his so-called purges or what is better known as the Great Terror. So none of this is true.

There is, in fact, quite a lot of evidence that Stalin did not kill Kirov. I lay out this evidence in the book. Other people have written about this as well, but it’s still a minority view. Most textbooks and most analysts hold Stalin responsible for Kirov’s murder in December 1934 because he benefited from the murder. That’s their deduction. However, this did not launch the so-called Great Purge. The Great Terror begins not right after December 1934, Kirov’s murder, but two years later. So we need a new explanation.

It turns out that Stalin was criticized for collectivization. He felt that it was his greatest achievement. He felt that he had done what nobody thought was possible—force those capitalist, breeding peasants, those 120 million souls, into these collective farms and destroy capitalism in the countryside. He did that. No one else could have done that but a figure like him, just as we had a figure like Mao in the Chinese example and Pol Pot in the Cambodian example. Once again, it’s no accident that these types of figures are necessary to carry out what only mass bloodshed can carry out.

They criticized him for what he regarded as his greatest achievement. They called for his removal, not openly, but they whispered about it behind his back. Instead of congratulating him, instead of lauding him and saying, “You know, we were wrong. You were right,” they talked about how he had caused all of this excess bloodshed, unnecessary bloodshed.

To him it was absolutely necessary. There was no other way, and he was right, so his resentment began to boil over. This resentment had developed earlier because of Lenin’s so-called testament calling for Stalin’s removal. This happened in the 1920s, and I cover that in Volume 1. And now, in Volume 2, we have the boiling-over resentment from the criticism in the party. All during the Great Terror of 1936, ’37, and ’38, Stalin refers more to criticism of collectivization than to any other factor.

One of the most fascinating psychological aspects of the purges and executions are the confessions that they came along with. What is your reading psychologically of what was going on there? Why did Stalin feel the need to have these confessions, even though many of them were fake?

You’re right. It’s a puzzle. Here we have a guy who gives instructions to the secret police about what should be in the confessions. When the confessions come back to him, he reads these confessions. Some of them are hundreds of pages long. He reads the so-called testimony. It comes back to him very close to what he instructed. He then edits it, and sends it back for further torture in order to extract the edited versions of the confessions that he prefers.

And then, when it’s to his liking, he begins to show it to his other minions and say, “See, I told you, spies and wreckers are all over the place. They’ve infiltrated everywhere. Look, and they’re implicating your own.” That is to say, his minions’ own subordinates. “You see this? You trusted so-and-so, and so-and-so is now implicated. What do you have to say for yourself?” So it’s almost inexplicable that a guy would act upon, and seem to believe, confessions that he himself dictated the content of; but these are the documents that we have for the Great Terror.

Moving toward World War II, what differences and similarities do you see between Stalin and Hitler?

So there’s a [few] people in Stalin’s category, and that would be Hitler and Mao, really. Hitler is also an incredible story in the fact that he’s Stalin’s contemporary and principal nemesis, which is really striking. What you have with Hitler is a guy who in some ways is even crazier than Stalin. That is to say, Hitler will take risks. He won’t take calculated risks. He’ll take risks, which are considerably uncalculated, and sometimes will pan out, and he’ll get lucky and sometimes won’t.

But the thing about Hitler and Stalin is that they both had ambitions. They both had aspirations for their countries to rise again as great powers in their own racist or class-determining ways. The Versailles Treaty of 1919, which many people blame for World War II, was an anomaly. The only way you could get that treaty was if both Germany and Russia were simultaneously flat on their backs. This has happened only once in modern world history, that time, post–World War I. And so the treaty was imposed on Germany without the participation of Russia. What happened was Hitler and Stalin brought their countries from their knees back to great power status in a single generation—and, of course, they then clashed against each other.

Why do you think Stalin was so unwilling to believe his advisers and his intelligence that Germany, in 1941, was on the verge of attacking the Soviet Union?

We have to look at the actual documentation, not what people later in their memoirs claim they said. For example, Churchill claimed he warned Stalin. There is no such warning in the documentation in real time. We have to look and see what Stalin was actually getting. What he was getting was a mess of information that was all hearsay. No foreign intelligence service ever got its hands on Operation Barbarossa, the Nazi invasion plan. That was only after the fact we saw that—that is to say, after the Nazis were defeated in World War II.

Stalin had overheard conversations, reported hearsay. Moreover, that hearsay was contaminated with disinformation. Because the Nazis understood that the Soviets had an extensive spy network, the Nazis used that spy network against Stalin, sort of like in judo when you use the strength of your opponent against that opponent. So they fed these Soviet spies with lies, and the lies were varied. But the key one—and the one that Stalin wanted to believe and therefore fell for—was that the massive German troop buildup in the east, right on the Soviet border, was not an invasion force but was to intimidate and blackmail Stalin so that he would yield Ukraine and other territories to Hitler without a fight. And this disinformation contaminated even the best spies that Stalin had, and that’s what he was reading and chose to believe on the eve of the war.

What has changed the most in your analysis from the time when you went in thinking something about Stalin before Volume 1 to now?

One of the things that I really didn’t understand was the depth of Stalin’s charm. I knew he was a very effective ruler in some ways, but I didn’t understand how not just intimidation, not just threats and blackmail, but his incredible charm was so effective for his rule.

He would bring people into his office. It was called the little corner. The Kremlin is a triangle, a citadel, a fortress unto itself, and Stalin’s building inside the Kremlin was a triangle inside the triangle, and his office was on the second of three floors in the corner, a little corner. And they would come, and he would know everything about them. They’d be summoned. They’d show up. They had never met him. They had only seen him in newsreels or from afar.

He would look at them. He would tell them everything about them and their work. He would explain the technology that they were developing. He had read the dossiers and prepared. He would give advice. He would give them a new apartment, or he would give them a telephone or some other perquisite, but it was the inspiration that they derived from seeing how in command of his brief he was, how lively a conversationalist he was, how conversant in modern technology he was, and they would leave that office ready to kill for him. He did that again and again and again. The more you see the inside of the regime, the more you see the profound loyalty to his person.

Was it ever emotionally exhausting to do these books, not because of the amount of work you were putting in, but because of the subject matter?

Yeah, and it still is. You know, evil is difficult to live with on a day-to-day basis.

There’s never been a regime more powerful than the Stalin regime, and let’s hope there never is a regime as powerful again. But living with this on a day-to-day basis, coming across documents where there’s blood, dried blood—it’s no longer red; it’s sort of a maroonish color. It’s fading, but it’s the blood of the people who were being interrogated and beaten to a pulp and in some cases beaten to death in order to make these confessions that you alluded to earlier. You live with that and, of course, it has an effect. At the same time there is this big story, which is the story of this individual, Joseph Stalin, and as you move forward in time, his biography, his personal story more and more resembles an entire history of the world.