This month marks the 50th anniversary of the murder of Che Guevara, the Argentinian guerilla who helped lead the Cuban revolution, fought in insurgent struggles from Latin America to Africa, and eventually met his end in Bolivia. Guevara’s reputation rests on his status as an iconic Cold War combatant and quixotic espouser of revolutionary ideals. That those ideals were often not matched by reality is part of what makes him both despised and tragic.

Jon Lee Anderson, the longtime New Yorker contributor and foreign correspondent, spent five years researching and writing Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, the definitive account of Guevara’s life. I called Anderson after he returned from Puerto Rico last week. During the course of our conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, we discussed why Che remains a totemic figure for so many, how Donald Trump, of all people, has shined new light on Che’s critique of America, and why the United States continues to view Latin America and the Caribbean as its colonial backyard.

Isaac Chotiner: How do you view Guevara’s legacy today, and has your view changed since you wrote your book 20 years ago?

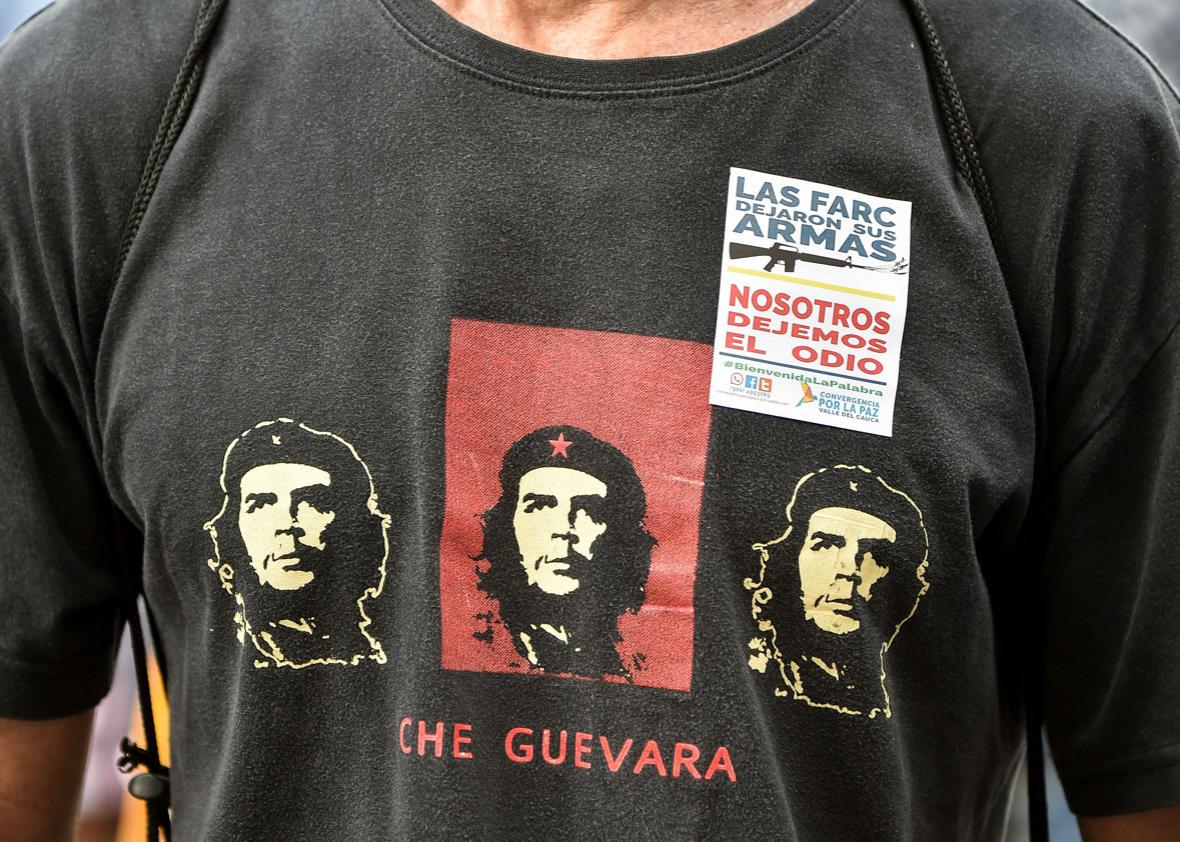

Jon Lee Anderson: I think Che’s legacy remains much as it was when my interest was first sparked in him in the late ’80s and pretty much through to the end of the book. While the world has changed somewhat, in the idea of an emblematic guerrilla, a universal paradigm for defiance against the status quo that appeals particularly to the young, Che remains the kind of universally recognized brand. Even if there are less guerrilla wars today, guerrilla wars have been replaced by terrorism. In that sense, he represents almost a rose-tinted throwback to a kinder, gentler era, as paradoxical as that may seem to some people. It’s still an unequal world and it’s full of political unrest, and to each generation and pretty much every culture he was the globally recognized brand of rebellion.

The paradox is that even though we live in this consumerized world in which everything is devolved down to a symbol, a visual symbol, that symbol in his case is nonetheless potent. It’s not just the same as seeing KFC on a storefront or the Coca-Cola sign. It’s Che’s face and it means something, and it means nonconformity against the global status quo and carries with it a suggestion of possible revolt or rebellion or political activism.

You used the word “brand” twice. There’s a certain irony in the word “brand” being associated with him given his place in the cold war, and his feelings about America.

Absolutely. He would groan if he were alive, roll over in his grave, any other cliché you want to think of he would probably do that. The fact of the matter is he came of age and became a mythologized global icon in the very decade that gave the world both the consumer society and pop culture.

He’s one of them. He’s one of the pop icons. There is a paradox in this idea of him being a brand. He, his family, the people who fought with him that are still alive, rail at this idea. We live in a world in which everything is a brand. He had one too, but he’s the only one of them which in a sense is not a consumer item or commodity. He represents an appeal to something different.

The further we get from the Cold War, at least in my opinion, the worse both sides seem. And Che embodies that as well. He was understandably enraged by America’s atrocious behavior; at the same time, his methods could be violent, and his own side perpetrated its own atrocities. Looking back on him and what he represents now, one sees tragedy and waste as much as idealism.

I’m not sure I agree entirely, Isaac. I’m not only speaking for myself here, but kind of as a perception of the world we live in, rather than a kind of deterministic comment. I think that we do respond. With differences in culture, I think worldwide we do respond collectively to romantic tragedy, if you will. This idea of vaunted and maybe abortive idealistic attempts to change things.

It may be a stretch to people who believe in Jesus Christ, but it’s not too far a stretch to compare him and this idea of yearning for a world that’s much more perfect and impossibly possible to achieve than the one we live in. With his own gripes, own travails, and ultimately miserable death, which we’ve turned into a religion, and Che’s odyssey on behalf of, as he saw it, of the poor and the downtrodden in Bolivia.

What is there to point to sweetness and light or optimism in Jesus Christ’s life? Yet, we for 2000-odd years, millions of people have been venerating him and in some cases, in some sects, actually praying and weeping fondly in the face of a carved wooden symbol of a bleeding man tacked to a cross. I’m just saying that I don’t know that in his failure or his tragedy it removes the idea of the legitimacy of his effort. I think it’s too easy to turn the page on history, or say that merely because his life was littered with death and ended in it, that it’s somehow ignoble or was pointless.

There is this idea that somehow it was his or Cuba’s fault for having created this paradigm for guerrilla warfare in the first place or guerrillas themselves, the left for having risen up as it were, and ultimately having failed and blaming them for the response of the United States and its counterinsurgency apparatus and the military dictatorships that seized power, and brutalized two generations and killed hundreds of thousands in response to the Cuban threat, or you could call it the Che threat.

Is that really a valid argument? Oh, so everybody should have just sat passively and allowed the future to take its course? I don’t think that’s the way history works. These weren’t ISIS. These were a cross section of Latin American society. It was a whole generation of youth. Not only Latin American. It was here in the United States as well. They were met with overwhelming violence in most cases. In a couple of cases they prevailed. We’ve seen the results. It’s a very, very mixed bag. Ultimately, it’s not a very pretty picture for the left in Latin America but it isn’t for the United States either. We’ve got Donald Trump in the White House.

How do you think Che’s legacy might have been different had he lived longer?

I’m not sure how familiar you are with Pepe Mujica, but he was the former Tupamaros guerrilla of Uruguay who became president a few years ago and held one term as president and kind of a wonderful, almost universally beloved figure. He was a Marxist, fought as a guerrilla, paid a very high price for it. I think he was 12 years in a hole. Nonetheless, he came out. Eventually became the president of his country. A small country that nonetheless has managed to restore a kind of democracy and have a level of civic freedom and, uniquely in Latin America, perhaps only seconded by Chile, rule of law that has eluded most other countries in the region.

Anyway, long story short, here’s a guy who once used violence or believed that violence was the only way to change society and has somehow found a way to adapt to the world and retain some kind of moral credibility. Che was a very different figure than Pepe Mujica. He was probably angrier and more outspoken and acerbic. I tend to imagine that if he’d somehow managed to survive he’d probably still be living in Cuba because it would have been the only place he could have survived. He would be curmudgeonly in the sense that he would always be willing to debate and he would be happy to debate on the world stage.

I think he would have evolved. He was evolving. I have pointed out to people that I feel he was evolving in certain ways when death caught him at the age of 39. People ask me about the firing squads of 1959 or his executions of traitors and so on in the Sierra in ’57, ’58. He was severe. He was damn radical. He was Robespierre for Cuba to the extent that it had one. Later on, he was different and in his last two guerrilla expeditions he didn’t execute anybody and he was a different man.

This is the Congo and Bolivia?

Yeah. He was coming up against walls. He was learning the limitations. He was maturing. He was evolving. I think he would have continued to.

How is he remembered in Cuba?

Well, I think to the extent that you could take a poll in Cuba, which you can’t, he remains the patron saint of revolution, he remains the both official and kind of socially recognized, nationally recognized validation of the revolutionary experiment in Cuba. He represented the high points. He is the emblematic figure that has been turned to and invoked officially in order to both validate what they’ve done and to re-inspire a new generation.

Now, have they always re-inspired new generations? No. The revolution has become a gerontocracy, as it’s had to grapple with some of its own failures and limitations, especially in the last 30 years since the fall of the Soviet Union.

What do you think he’d make of Cuba today?

Che kept his criticism to himself at the time when he left, but he was increasingly critical over the need to Sovietize Cuba. He was critical then, especially of the Soviets. He would be critical today of paths not taken, opportunities lost. He would nonetheless be a loyalist. He would look across the Gulf of Mexico, to Florida and the United States, and feel reaffirmed in his ideological decision all those years ago that the United States was a kind of bully or monster that was ruining the world.

He would look across the Caribbean to countries like Mexico with its drug war and corruption to Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador which are engulfed in gangland violence, and to the countries of Latin America which have gone from being rural to urban shanty towns. The poor are now in urban shanty towns in the Latin America where he once aspired to see a new socialist man rise up from the frontiers of the countries.

He would be deeply saddened I think. I think it would reaffirm probably his notion that capitalism was the ultimate evil and that some kind of new socialism was needed where egalitarian societies could come about in this kind of syncretic new world. Would he become a hedge fund guy? No. He would still be a revolutionary.

A lot of what drove Che Guevara, according to your biography, was the United States’ behavior in Latin America and the Caribbean in the Cold War period. Even though Puerto Rico is part of the United States, having just come back from there, do you have any thoughts about the fundamental colonialist nature of the relationship between America and the Caribbean? Have you considered these past weeks through the prism of Che?

I have absolutely. I first went to Puerto Rico four or five years ago. I was really struck because it felt like a kind of plantation. I was struck by its neocolonial status. This idyllic country in a perpetual state of dependency and a lack of definition of its actual status. A nation that could have been a contender but never was. I felt rather mortified really as an American that we had allowed that situation to continue for over a century. Certainly I would regard Puerto Rico as a place that is still in a kind of colonial situation vis-à-vis the United States. I think President Trump’s attitude and his remarks reflect his own racism towards anybody who is not of German descent seemingly, but of brown skin clearly, and also reflect those racial stereotypes that one is very familiar with in New York City where Puerto Ricans are always, at least for a number of decades and for people of Trump’s generation, were always looked down upon. Really, these are a people that have never been able to come together as a nation and therefore they are dependent and they’ve been in a vulnerable situation for decades.

I think Che would be extremely vociferous about the need for Puerto Ricans to separate themselves, to be independent, and he would be actively working just as he was in life in trying to inspire and in some cases actually materially help Puerto Rican revolutionaries who did try, in the ’70s especially and early ’80s, to rid themselves of the colonial subject’s mentality and to become a true nation, to become a people of a true nation.

Did you sense being there that feelings of independence could spark up after the way our government has dealt with the hurricane?

It’s difficult to figure out the percentages in Puerto Rico, although most people are tithed, so to speak, to the United States. It’s their safety valve, it’s where they go if they can’t find work in Puerto Rico. They’ve kind of been bought off. Also, in the sense of welfare, food stamps. They have family in the States. In a way, it’s an advantage over, let’s say, other people of the Caribbean, of the region. On the other hand, that very dependency doesn’t allow them to progress. This may change things or it could completely atomize the island once and for all.

What I did feel amongst all Puerto Ricans I met was that nobody’s happy with the status quo. They feel it’s the safest thing. It’s a pragmatic choice. All of them are deeply resentful at different levels. Deeply resentful of Trump, afraid of him. They recognize him for the bully-boy racist that he seems to be. They felt offended by him and his statements.

Hearing you talk today, you seem more positive to me on Che and his legacy than I got from reading your book. You have brought up Trump a lot, too, and I was wondering if he has changed the way you conceive of America.

I’m still figuring it out. I was never a fellow traveler or a drum-beater of Che. What I’ve always said is I was fascinated by him and I chose to write the biography about him and people have asked me, “How did you feel at the end of writing the book?” And I said, “I felt exactly the same way,” which is true.

I continue to feel that way today. Do I think I would have liked Che personally? Maybe not. There were aspects of his character I didn’t like. There were certainly periods I didn’t like. Overall, I am not personally or philosophically opposed to the idea of a legitimate revolution, historically speaking, when it seems to be the only way forward. I’m saying that very generally. Certainly, I think that the United States has behaved abysmally in its role as a superpower. It has mishandled its power and influence repeatedly in my own life. I have to say that it’s been very negligent, where it’s not been in some cases downright abusive in its relationships with some of our neighbors and our poorer neighbors.

But it goes beyond Donald Trump. It’s a problem of truly embedded racism and greed, frankly. If those people voted Trump into the White House in order to exclude others, to have more themselves, then you go back to some of Che’s fiery speeches, the one he gave at the U.N. and so on, and you know what? He wasn’t far wrong.

Maybe when I was doing the biography and the first years afterwards, I was seeing him as a historical figure. As time goes on, and I realize the United States itself is not settled in its own skin, that it hasn’t really evolved past civil rights, or we’ve gone forward and we’ve gone backward, and it’s worthwhile taking another harder look. I think we merit really harsh criticism.