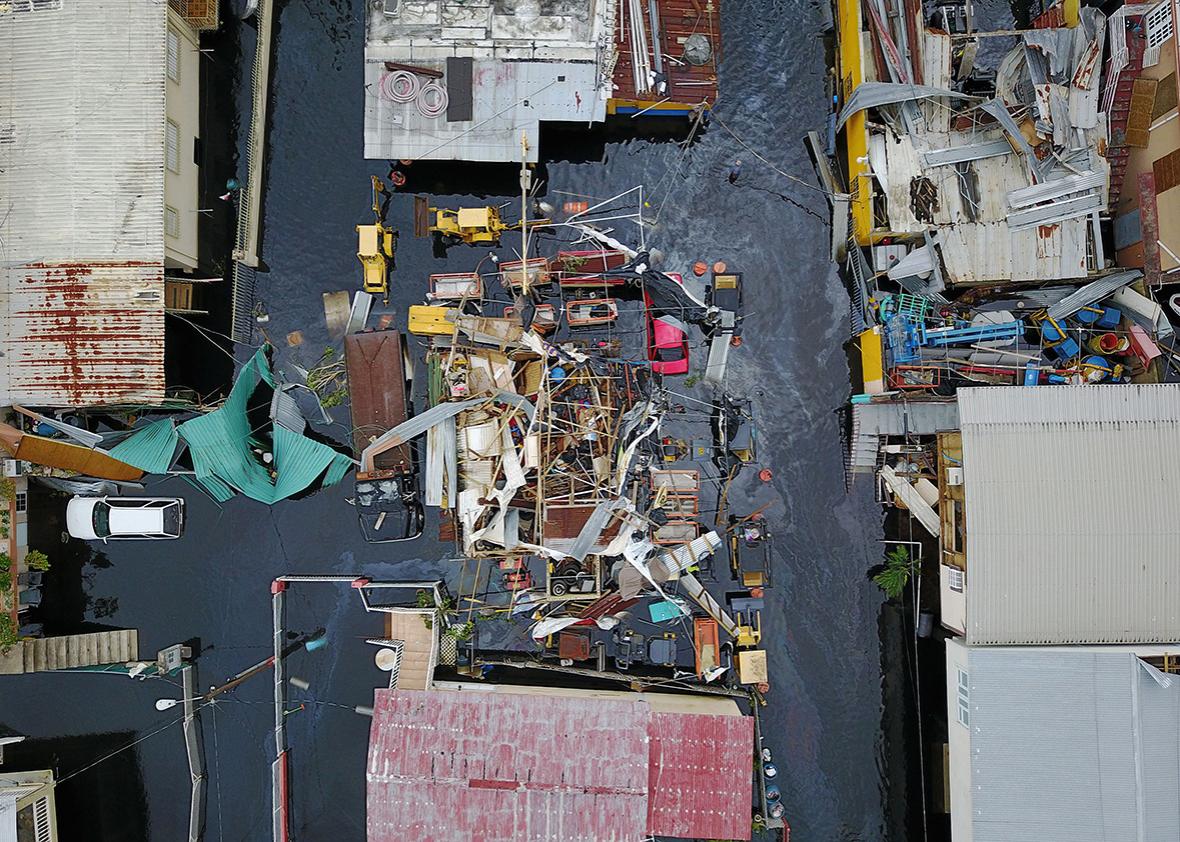

The devastation visited on Puerto Rico by Hurricane Maria over the past weeks—combined with the lackluster heartless response from the Trump administration—has for the first time in quite a while offered many Americans a window into the lives of people who they (erroneously) don’t necessarily think of as fellow citizens. Now, not only is the island facing a humanitarian emergency, but it also must cope with a teetering economy and a long-standing debt crisis that shows no signs of abating.

To discuss Puerto Rico’s past and future during the week that President Trump will visit the island, I spoke by phone with Ed Morales, an adjunct professor at Columbia’s Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race, and the author of the forthcoming book Latinx: The New Force in American Politics and Culture. During the course of our conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, we discussed the racist thinking that prevented Puerto Rico from becoming a state, the political importance of Puerto Rican identity, and why the hurricane is likely to damage any push for independence.

Isaac Chotiner: What about the unique history of Puerto Rico has made this crisis if not inevitable then perhaps not entirely shocking?

Ed Morales: Puerto Rico’s been a colony since the Spanish arrived at the end of the 15th century. Actually, when the United States had the war with Spain in 1898, Spain had granted Puerto Rico a form of independence, and that lasted for a couple of months until the U.S. then came and took possession of Puerto Rico. That’s one aspect: more than 500 years of being a colony.

And then there was the Downes v. Bidwell case. The language, that Puerto Rico belonged to the United States but was not a part of it, has a resonance to me with separate but equal. It turns out that some of the Justices that decided on separate but equal also came up with the Downes v. Bidwell decision.

If the main reasons why Puerto Rico was never seriously considered as a state after 1898 was that a lot of senators from the South brought up this idea that Puerto Rico had too many members of, they would call it, a mongrel race. Other times they were just talking about black people because there is an African component of the Puerto Rican racial mixture. It can be argued that a strong motivation for Puerto Rico never having been considered being admitted as a state is the racism that existed particularly virulently at the end of the 19th century.

You used the word colony, and I think when most people hear that word they might assume that Puerto Ricans therefore just wanted to be independent. But was this situation less clear-cut during the 20th century?

Yeah, it was definitely complicated. There were some people that favored the ties that we currently have, which is neither independent nor a state, and that’s based on the idea that Puerto Rico has a significantly different culture than the United States. Puerto Rico’s culture really resembles Cuba and the Dominican Republic. We have our differences, but they’re really similar. The other thing is there was a significant contingent or group of political leaders who did want to push for statehood at the beginning of the 20th century.

Interestingly enough, in terms of the race aspect, some of those leaders like José Celso Barbosa were part black. There was an idea about Puerto Rico becoming part of the United States to get away from the ruling elite that still existed from Spain, many of whom were lighter-skinned. There were some darker-skinned Puerto Ricans who favored statehood because they felt that there would be. … It would make Puerto Rico more egalitarian. They really believed in the idea of the U.S. A lot of that faded as it became clear that the U.S. was not serious about admitting Puerto Rico as a state.

Then when you move out from there, you get the citizenship, which happened in 1917. There’s a theory that the reason the U.S. did that was because they wanted more soldiers because they were running out of soldiers to draft for the latter part of World War I. But the prospect of citizenship was never offered to Puerto Ricans; it was basically granted or imposed. There was never an asking of the Puerto Ricans whether they wanted it or not.

It seems like what we have seen lately then is the worst of both worlds: Puerto Rico is not independent and it’s not a state, and it’s fallen in this horrible middle ground where they don’t really have autonomy, but they also don’t get the benefits that you get from being a state.

Yeah, that’s true. One thing I should say about that is commonwealth status, which is kind of a euphemism they use to describe it. That actually was reaffirmed recently in a Supreme Court decision that had to do with the debt, where there was some doubt about whether Puerto Rico could declare bankruptcy because it has this special autonomous status. Then the court said, no, it couldn’t because it’s an unincorporated territory of the U.S.

One thing that a lot of people who do Puerto Rican studies, that’s not my only field but I’m involved in it, talk about is that Puerto Rico has been used as a labratory by the U.S. over the decades. Some of the earliest examples are how a lot of Puerto Rican women were sterilized or used in birth control experiments that used drugs that hadn’t been allowed yet. A lot of Puerto Rican women were sterilized between 1930 and 1960.

The other thing is that when the U.S. began to give corporations tax breaks to set up malls, factories, and light industry, and then also all the chain stories and the American businesses, which are very common down there, they were practicing how they would use workers in a place where they didn’t speak English and that essentially were from a different culture. They paid Puerto Ricans slightly below the U.S. minimum wage, so the tax breaks and the slightly lower wage was something that was really advantages for these big companies that went down there to set up shop. When they passed NAFTA, then they got access to all these workers. This is something that really had a negative effect on the Puerto Rican economy. You could see that even though Puerto Rico’s economy had really begun failing as early as the 1970s, but it really begins to [get worse] after NAFTA.

What effect do you think Washington’s response to this crisis will have on how the island thinks about its status in the United States?

There’s already been, over the last five to 10 years, a lot of out-migration because of the economy. That’s going to accelerate. Some people are interested in really coming to the U.S., and living in the United States, and interacting with this culture. Other people are just leaving because they feel like they have to economically, and they’re just trying to survive. But the independence movement has really taken a huge blow with this because I just can’t imagine someone who would argue for independence right now, because the island is so decimated. It’s like, what do you start with? Statehood was also very unlikely. Now it’s even more so, but the U.S. actually is probably going to have to make some kind of federal investment, if only to create an atmosphere for its bondholders to at least get nominally repaid.

I think that one thing you can say about Puerto Ricans is they have a very strong sense of identity and culture. No matter what happens, that’s not going to go away.