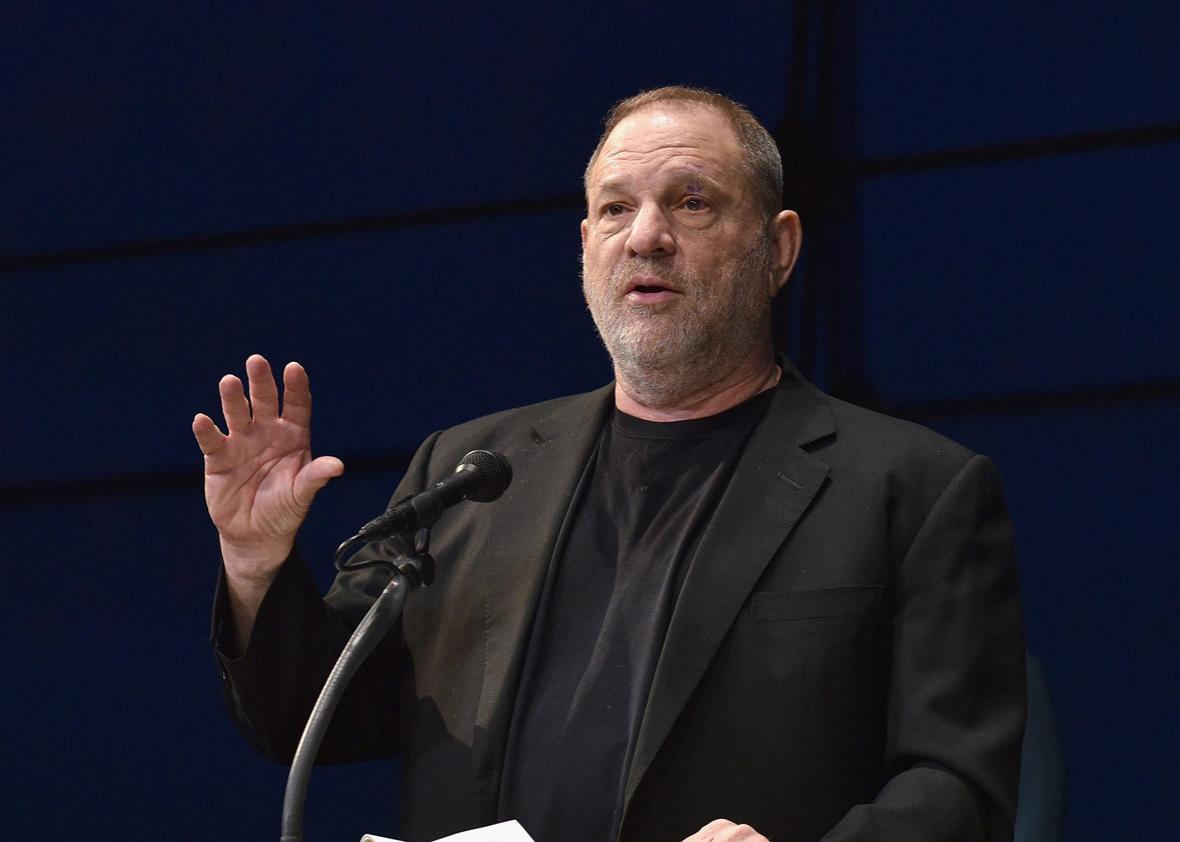

On this week’s episode of my podcast, I Have to Ask, I spoke with Jodi Kantor, an investigative reporter for the New York Times and a contributor to CBS News, who last week broke the Harvey Weinstein story wide open.

Kantor and her colleague Megan Twohey first published a massive account of Weinstein’s long history of sexual harassment and assault. She and Rachel Abrams then followed it up this week with more accounts of harassment by Weinstein from Gwyneth Paltrow, Angelina Jolie, and others. Meanwhile, the New Yorker released a blockbuster story by Ronan Farrow, including the accounts of several women who say they were raped by Weinstein, who has left his company and is likely to face some sort of legal action, unless he stays in Europe, where he has reportedly gone for “sex addiction” therapy.

Below is an edited transcript of the show. In it, we discuss Kantor’s process of reporting the Weinstein story, why a comprehensive account of Weinstein’s behavior hadn’t emerged in the press until now, why so many women eventually came forward, and whether Hollywood is really going to change.

You can find links to every episode here; the entire audio interview is below. Please subscribe to I Have to Ask wherever you get your podcasts.

Isaac Chotiner: Tell me a little bit about how you got on this story. When did you start and what was the impetus?

Jodi Kantor: The Times has made a real commitment to sexual harassment reporting this year. My colleagues Emily Steel and Michael Schmidt did the Bill O’Reilly story and Katie Benner had done some really startling reporting on women in Silicon Valley. So basically we said as investigative journalists we can look at the whole pattern here, and not just focus on one individual woman’s experience. Let’s see if there is a pattern of allegations over time.

So the editors came to us and said basically: What do you think are the biggest untold stories? And I did some research and I did some reporting and, you know, the Weinstein story was intimidating. It was clear that a lot of people had tried it over the years. It was so shrouded in rumor. It was very odd because on the one hand it was kind of an open secret, but on the other hand, almost nothing had been documented.

When you say it was an open secret—you read that “everyone knew” or everyone in the media knew or everyone in Hollywood knew—but when you started on the story, was it just at the level of rumor?

I will tell you something that looks really strange now. There is nothing more important in the film business than the Oscars, right? So if you look at the Oscar announcements in 2013, the comedian Seth MacFarlane is announcing the nominees … and says, “Congratulations ladies, you no longer have to pretend to be attracted to Harvey Weinstein.” I have listened to the tape and there is a lot of laughter on the tape. It is sort of like everyone in Hollywood was joking about a known thing.

But then, as we got further in our reporting, we found out that there were really serious allegations dating from as recently as 2015. And so it is sort of like people were laughing about this in the open when behind the scenes the alleged abuse was still going on.

How long were you on this story, in total?

About four months.

Was it a matter of you hearing all these stories and trying to confirm them as true, or getting people to go on the record versus off the record? Basically, what was the biggest challenge in taking your reporting and turning it into a story the Times can publish?

I think all along what we were looking for was clear evidence. And that can come in a lot of different forms. If you look at the two big stories we have done so far, which were the initial investigation that we published last Thursday, and then the story that we published [Tuesday] about the casting couch with these well-known actresses going on the record, they have a variety of forms of evidence. They do have on-the-record accounts from women, and those are really important, but they also have settlement information. There is the financial trail of the money that was paid out over the years. And then also there are internal company documents, which was a really important element of the first story, because we were able to show that these were live issues at the Weinstein Company. There is a woman named Lauren O’Connor who was a junior executive and in 2015 she wrote a stem-winder of a memo documenting sexual harassment allegations at the company. These were really upsetting incidents. She had a colleague who was forced, she says, to give Harvey Weinstein a massage in his hotel room when he was naked. The memorable line from that memo is, “The balance of power is me: 0, Harvey Weinstein: 10.”

So we were able to get that document and figure out that not that much had been done to address her complaints. That was very powerful proof, and I was happy we were able to get those written records because I felt, in a way, that we were taking some of the pressure off the women to come forward. And I say that with very mixed feelings as a reporter. Because on the one hand, of course I believe in women coming forward. That is in many ways what this entire project has been about. But on the other hand, there is something really unfair in sexual harassment reporting. In the course of reporting the story, some of the alleged victims would say to me, “How come it’s my job to address this? I was the victim. I don’t necessarily want to go public. I didn’t do anything wrong. Why do I have to do this?”

Now, obviously, as a reporter, I believe in people coming forward and believe it is my job to make it safe for people to tell the truth, but I really sympathized with their arguments about the kind of pressure that these victims faced. So that is why we wanted as many documents, as many records of settlements … and we wanted it to be irrefutable, because a lot of these things happened in the privacy of a hotel room, and we didn’t want a story that could be easily knocked down by Weinstein coming back and saying, “Hey, I was the only person there, and I am telling you that nothing happened, and that’s definitive.” We wanted other forms of proof about what happened, or I should say, the allegations.

Is your sense that you were able to get further on this story than other journalists, you and your colleagues and Ronan Farrow, because there has been a change in the air culturally, or that, as a friend suggested, maybe women were willing to come forward because the stories about President Trump led to a feeling that this was an especially important time that these stories be told?

I can tell you what our sources told us broadly.

I should have just asked that. What did your sources tell you?

I will tell you what they said because I think their reasons are more important than mine. Some of them were really heartened by the fact that the Times had such a strong recent record of sexual harassment reporting—that the O’Reilly story had worked and the Silicon Valley story had worked, and in all of those cases the women were believed and there was a lot of impact and a lot of accountability. And that made them feel, I hope, like we had the playbook and we had the experience to handle these stories right. Another reason they gave was, yeah, they did feel that the culture had changed somewhat, and the days of women being slimed for allegations, they hoped, at least, were over.

To be honest I think some of it is that Weinstein was a lot less powerful in Hollywood than he was years before. So many, many people were still afraid of him and I don’t want to understate that. But there was more of a feeling that he was at the end of his career.

And then I have to tell you one more thing if I am being honest: A couple of sources said they spoke to us because we are women reporters with a long history of reporting on women. There were sources who had never spoken to any other journalist who said things like, “Every other journalist who has approached me is a man and I want to speak to a woman about this.”

Did you come across people who had tried to tell their stories to other publications or journalists and felt like their stories were mishandled or ignored?

[Pauses.] I … don’t think I have anything interesting to tell you on that one.

You sure?

Well first of all I am not getting into confidential source conversations. I am willing to broadly characterize the attitude of sources. So the combination of that and not being sure of their—not being sure of people’s experiences, it’s just not—

Let me rephrase that. Do you feel like there was a broad feeling among people you talked to for this story, whether they were victims or not victims, that the press had failed to hold Harvey Weinstein accountable over the past several decades?

You’d have to ask them that, but honestly I think a lot of them were more consumed with their own feelings. We spoke to a lot of former Miramax executives and Weinstein Company executives who were quite tortured on these issues, and there were a number of people who I think ended up helping us because they had never really felt resolved with some of the things they had seen and witnessed there.

Were you nervous about getting any pushback, or about the pushback you got? I think the first I heard of this was the Hollywood Reporter story saying Weinstein may sue the Times and the New Yorker. How anxious were you about that and how much pushback was there, and when did it start?

I am just thinking about your question. [Long pause.] I’m just letting the last week sort of rest with me for a second before I talk. [Pause.] I knew we were going to get pushback. I will tell you the way I felt. Harvey Weinstein assembled this really large team to deal with us. So in the final days of preparing the story, we were interfacing with Lanny Davis and we were interfacing with Lisa Bloom and with Harvey and he hired this powerful attorney, Charles Harder. And part of the experience of closing that story had to do with their responses [being] very varied and [kept] changing. If you picture a piano where apology is on the left hand of the keyboard and denial is on the right hand of the keyboard, they were playing both sides of the keyboard and everywhere in between, and it kept moving. So I think in terms of the pushback, part of what I was concentrating on as a reporter was this sort of fundamental question like “are they denying this? Or is he apologizing? Is he disputing the facts here?” Because whatever his reaction is, we want to capture it correctly, but we are hearing a lot of different reactions from him.

That’s interesting, because I thought that was the problem with their PR strategy. It wasn’t clear whether they were saying “we are going to go after you because it is bullshit” or they were saying “we are somewhat contrite but not totally contrite.” It was a somewhat confusing public strategy as well as private strategy.

[Laughs.] Your observation.

Did you get a sense that Weinstein-like behavior is a bigger problem in Hollywood than you imagined? Did people talk about this as more or less common than we think, and did it change the way you think of the industry at all?

Yes. I had a lot of conversations with actresses about this topic and here’s what I would summarize of what I have learned. Based on everything I have learned, I think casting couch behavior is not at all dead in Hollywood. It still persists. But a lot of it is relatively casual. A lot of actresses will say, “Yeah, a few times in my career I have had an unwelcome hand on my thigh from a producer,” or “I have had a leering, inappropriate comment at an audition.” But Weinstein’s harassment appears to have been different. And part of the journey of the reporting over the summer was beginning to see and understand that he appears to have had a system and a methodology.

Megan Twohey and I had a version of one of those journalistic “aha” moments where you have been putting all these puzzle pieces together and then you begin to grasp that there is a larger mechanism that you are looking at. What we became convinced of, and then very committed to documenting, was that this wasn’t a case of a producer hitting on some women at a bar, right? This was much more organized than that. What I think we have now been able to prove, both through interviews with actresses, but also the assistants and the executives, is that there was a lot of facilitation here. Weinstein’s MO, as far as we understand the allegations, is that he lured women to private places, usually hotel rooms, with the promise of work. He would say, “I want to discuss a script with you,” or “I want to discuss your Oscar campaign for this movie,” which for an actress is like—who isn’t going to go to the hotel room to have that conversation? Those meetings were set up like work meetings. If you listened to Gwyneth Paltrow’s story, she says of course I went to the hotel suite because the meeting was set up on a fax from CAA. It was my agent telling me to show up at that suite, so it really did seem like a normal work thing.

And then once he had the women alone, that is when they say the tables were turned and they realized the work was just a pretext and they felt very lured and manipulated, and they were really there for him to make advances on. And all of that demanded support and facilitation. There were logistics with the hotels, assistants who set it up, there were travel agents, there were people who arranged the meetings. There are even accounts of Weinstein Company executives having to wait downstairs in the lobby, and when the women came down, they would be helped with casting and finding agents, etc.

Do you have some sense of the effect this will have or not have in Hollywood? I mean, this is still a place where, as you say, this goes on, and still a place where Roman Polanski has no trouble casting his movies with famous and big-name actors and actresses.

We are a couple days out from when we published so I think it’s a little early to discuss the impact. We know the impact in terms of conversation is enormous, but I think the impact will be constructive and this is the reason: Very late in the reporting process, someone said to me, “Because Harvey got away with this for so long, it sends a message to everybody else that they can get away with it too.” And essentially there is no accountability for serious sexual harassment allegations in Hollywood. My hope is that now that all these women have spoken up—it’s been an incredible array of women, ranging from actresses who are kind of barely even actresses, barely even in the industry, to top, top people like Angelina Jolie and Gwyneth Paltrow, they have collectively said, “This is a big problem.” And Hollywood now has to grapple with the moral question of, really, how you can accumulate 30 years of allegations and nobody stopped it? Who was protecting the women? And who was protecting Harvey Weinstein?

And then you have all of this cultural history in question. All of these years of Oscars and Sundance and Cannes and awards shows and movies that you and I watched on the big and small screens. There are all these questions about those years and what really happened then and what kind of abuse may have been happening off screen. Now that all of that is in question, I do think it forces a powerful conversation in Hollywood.

You must have been aware that Ronan Farrow was working on something. How much of an impetus was there to have the first story, and when his story came out—and I would ask him the same question if I have him on the podcast—how much had you heard about the various accounts and just weren’t able to nail down?

We were kind of dimly aware that he was working on something and then at times it came into sharper focus. It was a little confusing for us because at first I guess he was reporting it for NBC, and then he was reporting it for the New Yorker. It all makes sense now, but at the time we were confused about what his project was or what direction he was going in. We were aware of it, and then when I read his story—and by the way I congratulate him on his reporting. To state the obvious, I think it is a case of how journalistic competition can be really healthy. When I read Ronan’s story, part of me thought, “There appear to be more than enough allegations to go around.”

What does it mean that you can do this entire long New York Times investigation that’s thousands and thousands of words, and then a few days later you can do this enormous New Yorker investigation that is thousands and thousands of words and the accounts are both filled with these devastating allegations, and yet there is remarkably little overlap between the two stories. I think it is a great demonstration of how we now have to ask ourselves, “What is the size and scope of this thing, and how much more is out there that we haven’t even learned about.

Do you have any idea why his story didn’t appear on NBC News in some form?

Oh, I can’t speculate on his project.

Sharon Waxman has come out with a report saying that the New York Times in 2004 “gutted” a piece she wanted to do about Weinstein because of pressure brought to bear on editors at the Times. Was her version of this story something you were aware of and have you talked to anyone in the building about it?

Not really.

Can you say, when you were reporting the story, was there any pressure brought to bear on the Times that was then communicated to you by any people at the Times?

Yeah, I will tell you what the pressure from the Times was. The pressure was “nail the story.” The pressure was Dean Baquet saying, “Deliver the goods. Go get it.” The pressure was seeing the publisher, Arthur Sulzberger, in the cafeteria and knowing that he was protecting us, and knowing the institution was standing by us. So Megan Twohey and I felt enormous pressure to deliver the best, strongest story we could. And it was so meaningful when we were talking to the alleged victims to say, “The New York Times is so committed to this. This institution is willing to lose advertising and this institution is willing to stand up to this guy who can be a very intimidating figure.” Anyway, I should leave it there, but there was a tremendous amount of pressure, but the pressure was to get the story, not to abandon the story.