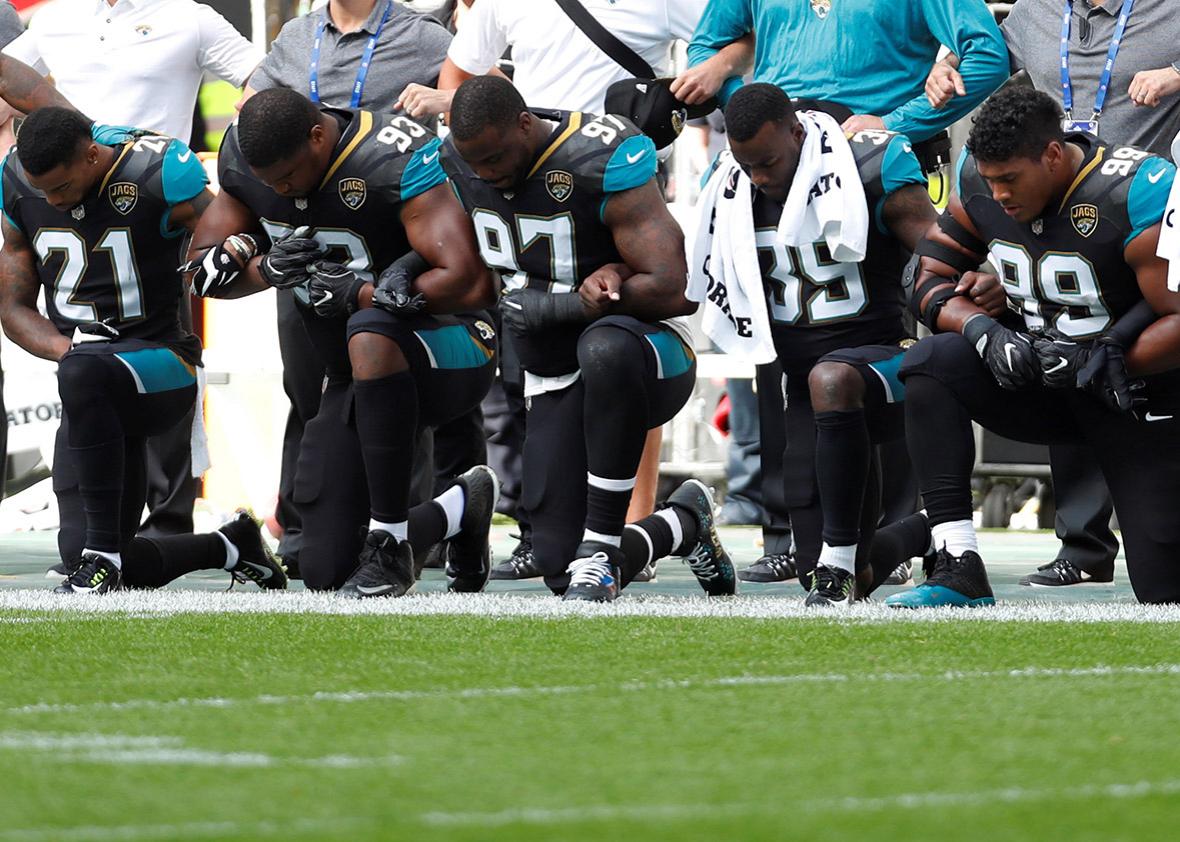

At a now-infamous rally on Friday night in Alabama, President Trump stated that NFL owners should fire players who “disrespect” the flag. On Sunday—during a weekend in which Trump kept tweeting about the issue, and then went after Steph Curry of the Golden State Warriors—sports commentators, coaches, and players across professional athletics not only criticized the president, but engaged in various acts of protest and solidarity.

To discuss the controversy and the intertwined histories of race, sports, and politics in America, I spoke by phone with Gerald Early, the chair of the department of African and African American Studies at Washington University in St. Louis. During the course of our conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, we discussed why sports and politics have always been intertwined, what is and isn’t unique about Trump’s comments, and the long history of viewing black Americans as ungrateful.

Isaac Chotiner: Do you see any historical precedent for Trump’s comments or the scope of the response to them?

Gerald Early: I don’t recall any incident where a sitting president went after a particular sports industry in the way that Trump did. I mean, there have been politics in sports, of course. But the idea that an entire industry, an entire sport, would be attacked in this particular way is, to my mind, unprecedented.

Athletes obviously have a very interesting place in our culture, and there are a lot of black athletes. Does the way we think about protest differ when it is athletes doing it?

Race and sports in the United States has a long and complicated history. What you had in the United States for a very long time was a crisis within sports itself, because sport was supposed to be this area of fair competition. It was supposed to be that an athlete succeeded on the basis of his or her skill, mostly his skill, and the like. And skin color, nothing else measured into this. So, it was supposed to be the epitome or realization of the whole idea of a liberal philosophy of the idea of fair play, and the individual and all this sort of thing

And it ran up against this other major reality in the United States: The United States was a racist state. And so, that was where the conflict occurred in sports, which resulted, for instance, in the late 19th century, the creation of two different types of professional baseball leagues that were based on race, and that existed in this country until the end of World War II. And you know, people talk about race and sports, and politics having no place in sports. But, I mean, the division of baseball in this country by race is explicitly, self-evidently political. [Laughs.] I don’t know what else you could call it.

You could look back to, of course, Muhammad Ali is the most obvious figure. But you could look at a figure like Curt Flood in baseball. You could look at a figure like Joe Louis, you could look at Jackie Robinson, you could look at an earlier figure like Jack Johnson.* You could look at a number of instances in American sports where the crisis with politics and sports in this country frequently has been over the business of race.

When you said the thing about sports was supposed to be a place with fair rules that sort of upheld the American ideal: Do you think black Americans saw it that way too, or just white Americans?

I would say that white people clearly believed something like that and promoted that ideology around sports in the United States. I would say black people believed it too, but they believed it for different reasons. They believed it because OK, in sports, if I’m given the fair opportunity, I can show what I can do because it was the belief by both parties, for a long time, that sport itself was not inherently political. It was other type of manipulations that were making it political, but that sport itself was this area that was nonpolitical. So black people believed that if only we were given our fair shot we could succeed in this. All we want is a fair shot at succeeding in this. And whites for a long time had, of course, the liberal ideology of, oh, there was fair competition, merit wins out in the end, best athlete wins.

So both parties came to it but for different reasons. Believing, wanting to believe that sport is the area of liberal colorblindness. Now, naturally, as black people performed in sports and became involved in sports, they realized that in fact it was no haven of colorblindness. It wasn’t any raceless sort of thing. It’s a product of a society, it’s functioning in a society, it’s meant to promote a kind of belief in a society—and in a country that was also a racist state as the United States was, it was also meant to endorse that ideology as well. A racist ideology. So, black people found themselves finding that sports was not what they had hoped it would be.

Do you think the protests like the ones we have seen around police brutality should stay focused on systemic racism, or do you think they should be more about Trump? Because it sort of became a Trump thing this weekend.

Well, what happened yesterday was clearly in response to Trump. And you know, I guess one of the things that Trump did that was kind of surprising was that he brought labor and management together yesterday, because people thought that their industry was being attacked, so that’s why they were able to come together the way that they did. But, originally with Colin Kaepernick, and with other kinds of things that were happening before this, for instance with LeBron James and guys in the Cleveland Cavaliers wearing shirts that said “I can’t breathe,” and everything, it was really starting out as … an increasing kind of awareness or radicalization, whatever word you would want to use, of African Americans over these high-profile police brutality cases.

This new wave of protest I think would have its origins probably with the Trayvon Martin case. And then it intensified incredibly with Ferguson and the Michael Brown case. And then it was Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice, and other cases that occurred. But, it was all, I think, on the part of these high level athletes who are very well paid and so forth, to show that they had … they understood that they were still black people. That they wanted to express solidarity with black people and what they were experiencing. And they wanted to use the platform that they had. I think that they hoped they could legitimize it because of their standing in the culture. And because in some ways, these black athletes are bridge figures. I mean, they reach more white people and are admired by more white people than most black people are.

I think shifting to Trump is maybe problematic. You might be deflecting from the original intention and the original purpose of what these protests were about, and what people were trying to express originally with these protests. And for black people, in doing this, in doing this with the national anthem and so forth, it was basically saying, look, we’re not the same kind of Americans as other people are. We are a different kind of American. Our experience has been different. And our feeling about the country is different. And we feel that that should not only be recognized, it should be respected.

And so, the Trump thing is, to my feeling, to my mind, in some ways it’s good because it’s kind of intensified things. But on the other hand, it kinda in some ways moved things away from the original purpose of this. Then it becomes involved with the movement [against] Trump, which I think it’s a kind of mixed blessing. It’s not necessarily entirely good to be involved in fooling with Trump. And Trump is not an idiot.

We disagree there, but go on.

I think Trump did this in part because he wanted to play a certain kind of race card. Because he was focusing on sports, where there are a high number of African Americans. And to his base, these African Americans who are very successful in these sports, are very highly paid, and so, it’s easy for him to use them to many of the disaffected whites who are Trump supporters, to say look at these ungrateful black people.

That seems right. Most Americans do not like Trump, so you get the broader appeal, but you do lose the original focus.

It deflects from what the original thing was. And I think the original thing that was driving people out there—with the police brutality stuff, with the rise of Black Lives Matter, and so forth—was in some ways to me more important than being part of an anti-Trump movement.

About the “highly paid” stuff, Chris Rock made this comment about how actually athletes are people who made it on their own and their success is due to their work, unlike inheriting real estate money from your dad, just to pick a random example.

Sure.

But Trump is trying to portray these guys as, like, spoiled. Is there a history that you can think of within American racism specifically, about trying to say that black people are actually privileged or they’re actually elites?

I think it definitely goes back to the rise of affirmative action. I think affirmative action has always been seen as people who are getting stuff that they shouldn’t be getting that they don’t deserve. And I think it’s been a great cause of white resentment in that regard. But, you know, oddly enough, arguments about black people being well treated and things like this, believe it or not, go back as far as slavery.

There were, in the South during the days of slavery, pro-slavery people who argued very much that black people were in fact well treated under slavery, and were in fact quite privileged and better off than whites who were working in the industrial North. They were being taken care of. They were being provided with their needs. So, actually there’s been, if you look at the history of this country as a racist state over the past few hundred years, it’s always been an undercurrent of an argument here that actually black people have been treated well, and people don’t recognize this. And black people don’t appreciate it. And in fact, black people have been unfairly resentful for the way they’ve been treated.

After all we’ve done for them.

And I think there’s always been this sense that black people don’t have gratitude. And I know that sounds incredible to say that with slavery. But, I mean, the pro-slavery argument was well, we took them out of this savage Africa.

It’s the pro-colonial argument.

Yeah, it’s the colonial argument, exactly. We gave these people civilization. We gave them a religion. We’ve brought these people up. And dammit, they don’t seem to appreciate what we’ve done.

*Correction, Sept. 26, 2017: This article originally misspelled Joe Louis’ last name. (Return.)