In a big new academic paper that has occasioned much discussion in the world of political science, Joshua Kalla and David E. Broockman put forth the possibility that campaigns may matter a lot less than everyone—from average citizens to Beltway pundits—assume. “We argue,” they write, “that the best estimate of the effects of campaign contact and advertising on Americans’ candidates choices in general elections is zero.”

There are some crucial caveats here: The authors are studying general elections, rather than primary campaigns; they are working with a sample size; and, as they write, “campaign contact in general elections appears to have persuasive effects if it takes place many months before an election, but that these effects decay before Election Day.”

To discuss the study, and what it means for how we should think about politics, I recently spoke by phone with Kalla, a graduate student at the University of California–Berkeley. During the course of our conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, we discussed whether this research should change the way the media covers politics, what campaigns can still do to change people’s minds, and why hardening partisanship may alter how a candidate’s money should be spent.

Isaac Chotiner: How did you come to the conclusion you did?

Joshua Kalla: I think there are very important caveats in the paper, but at the very least, our one general takeaway should be skepticism that there is a big persuasive effect in American politics from an additional TV ad or an additional knock on the door or an additional mailer; that the effects that come from these direct campaign contacts are probably very small, if not zero; and that any argument to the contrary should be met with skepticism and should require some sort of evidence behind it. That’d be one takeaway.

How we went about answering this question was from really building on two decades of experimental research in campaigns. Just like how in clinical medicine we test whether a new drug is effective at lowering cholesterol by conducting a randomized experiment: We get a bunch of people who have high cholesterol, and we enroll them in a clinical study, and we randomly assign half of them to get the existing cholesterol drug and half of them to get this new drug we want to test.

This model that has existed in medicine for 100 years, in the last two decades, has really taken hold in political campaigns. Just like you can randomly assign people to take drug A or drug B, you can randomly assign people to get the knock on the door from the campaign, or to not get the knock on the door, to get this mailer, or to get that mailer, and you can measure whether or not it changes people’s attitudes or whether or not it changes their voting intention.

So what we do is we build on, first, 40 of these experiments that have been conducted over the last two decades, and then we conducted nine new ones of our own in 2015 and 2016 during those elections. We took all 49 of these and combined them together where many studies is more informative than just one study. It’s called a meta analysis. By combining these 49 studies, you’re looking at very precise answers on the effects of campaign ads.

But how do you define what a campaign is? Campaigns have definitely gotten longer over time, so when you’re defining something like “early in a campaign” or a “late in a campaign,” how do you define that?

I want to be very clear that campaigns encompass lots of activity. The things that we study are the direct campaign contacts: It’s that piece of mail, it’s that knock on the door, it’s that phone call, it’s that additional advertisement. Campaigns are obviously more than that.

Campaigns are what issues the candidate chooses to emphasize and take on, who the candidate is. It’s those press interviews. It’s those press narratives. It’s those campaign biographies. None of those things we actually study in our paper. Our paper is much more focused more specifically on those campaign advertisements and those campaign tactics, those kinds of direct outreach between the campaign and the voter. Those other things that I mentioned, they might matter, we just don’t really know at this point. We don’t really, in our work, speak to that.

To answer your question on early versus late timing, how we define it in the paper is, two months before Election Day we define as late in the campaign, and anything prior to two months we define as early in the campaign.

Do you have a theory on why some outreach early in campaigns tends to work even if it does dissipate over time?

It’s one of the things that we hope in future research to really unpack, which is why that persuasion early seems thoughtful but doesn’t last. If I were to speculate, early in a campaign many people aren’t paying that much attention to politics, they might not know the rest of the campaign activity that’s going on, they might not know about the other candidates. So early on, they might be persuaded by that knock on the door, that piece of mail, but by the time the campaign runs around, either they’ve forgotten that early contact or they’re returning home to some sort of starting point that they already had.

That’s an interesting thing about returning to the starting point, because I think one of the crucial things about your paper is that you’re talking about general elections, not primaries. And as we know about primaries, there’s not the same partisan pressure on someone to vote a certain way. Even if you know Bernie Sanders versus Hillary Clinton is fraught, there’s not that kind of tribal feeling about it.

What I thought reading your paper, at least, was that early in the general election campaign, your sort of tribal feelings, in our polarized political environment, have not been totally activated, and so you’re kind of more open. We saw this with Trump. Early on, his approval ratings, even among Republicans, were not great. Eventually, by Nov. 8, that tribalism just became fully entrenched.

Yeah. I think that’s very consistent with what we find—which is in primary elections we do see persuasive effects. Also early in a general election, we don’t really have data on this, but I think you’re right in speculating that early in an election, people’s partisan identities are not fully activated, but closer to Election Day, as those get activated, any sort of out-party persuasion is much less effective.

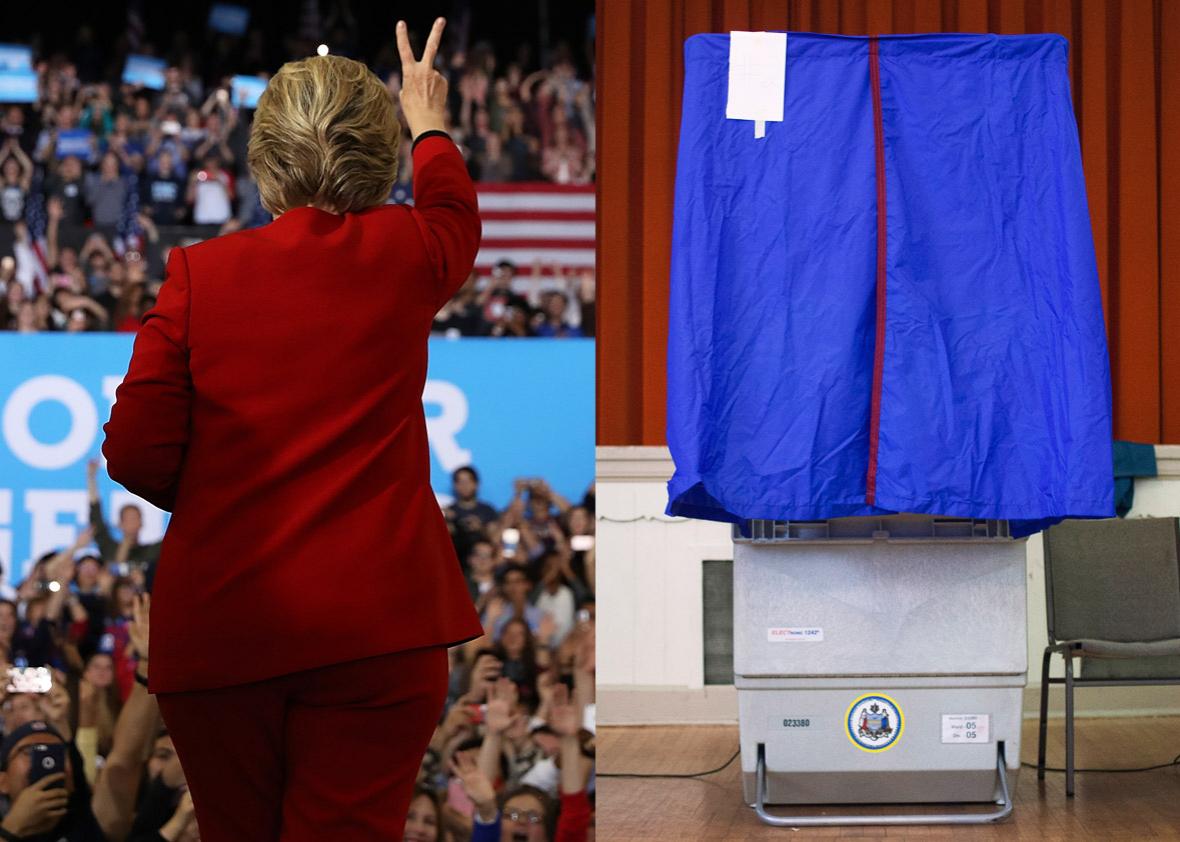

What does your paper make you think about the way politics is analyzed by the press and political pros? We’re still having debates almost a year later about whether Hillary Clinton should have made two more stops in Wisconsin which, to me, always seemed crazy. Maybe that’s my bias, but it does seem like, if your paper is accurate, or at least if we don’t have a political science version of the opposite take, that it really calls into question some of the ways we analyze politics.

Yeah. I think being retrospective is always very easy. Monday morning quarterbacking is easy. How a lot of campaigns are thought about is: Your candidate won, everything that that campaign did must have been effective, and if your candidate lost, everything that candidate did must have been ineffective and must have been wrong. I think these kind of anecdotal stories are probably misattributing what campaigns get right and what they get wrong. I think when it comes to evaluating these retrospective claims about what campaigns should or should not have done, one big issue is we often don’t know. There’s not good evidence on what is the effect of a candidate campaign rally in a battleground state a week before the election. We don’t know what the answer is to that question.

One takeaway from this paper should be that it’s possible to scientifically evaluate campaigns and campaign tactics, and once we know what works and what doesn’t work and why, then I think we can have much more informed debates on these retrospective evaluations about what campaigns should or should not have done.

OK, but when you say what campaigns should or should not have done, if it doesn’t matter, what should campaigns do? What’s the upshot here?

First, we do know that campaigns have activities that matter. I think a key one, which we talk a little about in the paper, is that there’s two decades of research on voter registration and voter turnout which show that campaigns can be very effective at shaping the electorate in ways that are favorable to them and mobilizing their base to get out and vote. That’s clearly one thing that campaigns should keep doing and there’s really, really good research behind it.

And then when it comes to persuasion, we find that there are oftentimes pockets of persuadable voters who campaigns can reach, but that knowing who these persuadable voters are is very hard. A focus group probably is not the right way to figure out who these voters are, but an experiment with the latest advances in machine-learning or algorithms can tell you who are the voters who are actually moving the vote choice, and campaigns should use that to strategically charge those voters.

I think that’s one thing that more campaigns ought to be doing. I think the final thing is clearly voters change their minds. Some voters voted for Obama in 2012 and Donald Trump in 2016. There is persuasion happening in American politics. That persuasion probably isn’t because of a piece of direct mail, but the fact is that persuasion exists in American politics because there are people who are changing their minds from Obama to Trump or from Romney to Clinton. That means that there are tactics that campaigns could develop and could use to their advantage.

I think one comparison is this work that David and I have around deep canvassing and changing attitudes around transgender rights. The campaign script that [the Los Angeles LGBT Center] used and that worked, which really took them six months to develop and eleven iterations, draws on a lot of ideas from social psychology, political psychology, political communication, and uses that to come up with an effective way to change voters opinions around transgender discrimination.

I think it is possible to change people’s minds on the very hard issues. I don’t think campaigns should totally give up on persuasion. I think campaigns should re-evaluate what it is they currently do and question a lot of the assumptions that they currently have, so that they can develop new ways to effectively persuade voters.