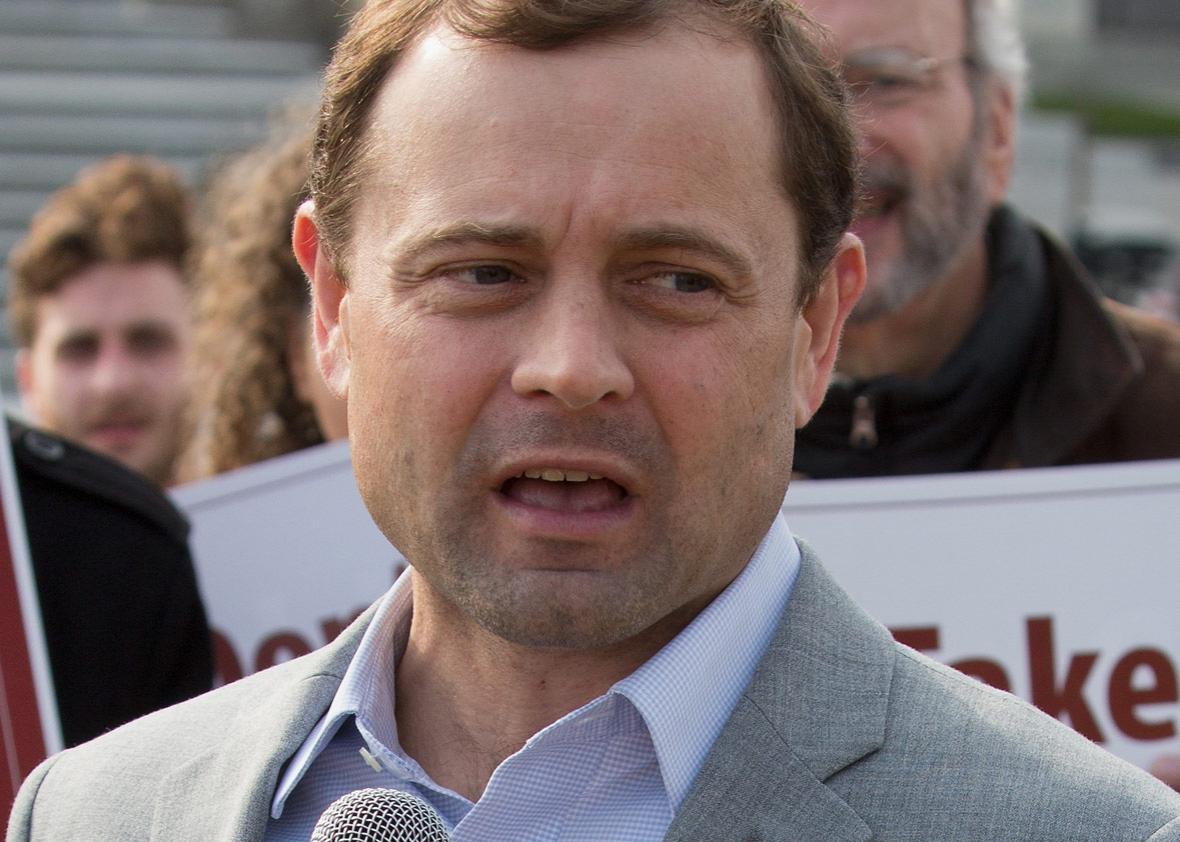

Last month, in the Democratic primary race to become the next governor of Virginia, Tom Perriello lost an election that some saw as a referendum on different wings of the party. Perriello, who served in both Congress and the Obama administration, ran a consciously anti-establishment and self-described “pragmatic populist” campaign but fell short, garnering 44 percent of the vote against the state’s Lt. Gov. Ralph Northam. (Northam, who supported George W. Bush twice, ran as a fiscal moderate.)

Perriello is now spending his time with a political action committee called Win Virginia, which aims to focus attention on the fight for Virginia’s House of Delegates and non-national races more broadly. During the course of our recent telephone conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, we discussed why Trump’s racism played especially well in the suburbs, why progressives give insufficient attention to state and local elections, and whether the Democratic Party can serve both an urban elite and those left behind by economic change.

Isaac Chotiner: In all the conversations about the future of the Democratic Party, what sticks out to you, or has been overlooked?

Tom Perriello: I think whichever party figures out the way to talk about and express the economic challenges of automation and monopoly will own the political landscape for the next few decades. I think that we’ve been trapped in a couple of false choices. One is whether this last election was about economic anxiety or racism. It was clearly about both of these dynamics and how they interrelate with each other. Second, there’s a more niche debate about whether the economic challenge of the day is primarily about automation or monopoly, when, again, it’s the toxic intersection or interrelationship of these two.

Why do you think your race turned out how it did, then, because you became known for the way you were talking about these issues, especially ones having to do with monopoly?

We did well with the groups Democrats struggle with in off years. Millennial voters, rural voters, and voters of color below the age of 65. Unfortunately, those groups do not make up a significant enough part of the Democratic primary. I think it also hurt us that we were essentially outspent 2 to 1. I give Ralph a lot of credit for running a great campaign and for raising the resources. I think, as I’ve said before, a candidate more talented than me could come along with some of the message we tested and probably do a lot better.

OK, but when you were talking about those issues, did you think they were registering?

Yeah. In fact, it was sort of funny, because for me, I’d have a lot of days where I would start outside the Beltway in either, you know, call it Trump country or key blue pockets outside of the Beltway. People would be raising these issues with me. So we’d have a very sophisticated conversation about them. Then I would end the day at an event inside the Beltway, where people were saying, “Tom, you can’t run on this message because those people aren’t sophisticated enough to understand these issues.” I’m like, “They’re the ones bringing it up to me!” Automation has killed more coal jobs than natural gas has. It’s not hard to go into these parts of the country, or the commonwealth, and have conversations about this. It’s already people’s lived experience.

A friend of mine suggested that one of the reasons you didn’t do as well in Northern Virginia as maybe you’d hoped was that the wealthier Democratic areas are becoming more and more allergic to populist messages, which creates a schism within the Democratic Party. Do you think that’s right?

Look, I think that there is genuine overlap in interest between much of our base and rural white voters today that did not exist before. But there is some tension between that set of issues—which certainly involves being more critical of corporations, in particular monopolies—than some of the urban elite part of our coalition is comfortable with. I think some of this, too, is that attitudes in rural Virginia right now towards mental health, criminal justice reform, and a living wage are in a much more progressive place than they are with some of the suburban Republicans that we would otherwise want to try to appeal to. I think there probably are some trade-offs there of which group we’re trying to entertain.

The core challenge here is: We either run on a platform that says the economy is basically working but we need to tweak it for groups that have been marginalized, or we need to understand that the economy is fundamentally broken for a growing number of people—and I think if we are essentially the status-quo-with-elites party, that’s going to appeal to a more and more narrow set of voters. If we actually think we might have something to learn from listening to folks about how broken the promise of social mobility has become, then it’s a different story. This is captured with the difference between whether you stand for the traditional approach of a $2,000 tax credit for tuition, or something like two years of free community college, or more. I think those are speaking to different experiences.

I also have a belief that was strongly reinforced by this campaign. I think Trump’s racism played as a bigger factor in the suburbs than it did in rural Virginia—in part because race has always played in rural Virginia, but I think the encroachment of immigrant communities are relevant. You see that with the fact that Corey Stewart, who ran on an explicitly neo-Confederate platform in Virginia, and was not taken very seriously, came within a point of becoming the Republican nominee. And he’s an elected official not in rural Virginia, but in Prince William County.

So why is that about racism and the suburbs, do you think?

Traditionally, trying to play on this dystopic vision of a violent, black, urban environment that threatens you, your family, is something much more directed at suburbs than rural communities. It’s not to say that racism doesn’t exist structurally and overtly in rural communities, but that has been relatively static. If you look, there are not very many people losing their jobs in rural Virginia who feel like they’re losing it, their job is being taken from them to be given to the black guy they see on the street. But that’s where we get into the automation point, which I’ll come back to.

In suburban communities, that’s where you have families who have done everything they think is right, probably got into college for free, gotten themselves a two-income home. … Granted, probably 1½ income. For 10 or 15 years, they haven’t seen a raise in a meaningful, inflation-adjustment sense. They haven’t gotten the country club, etc. And when Trump plays about political correctness, I think he’s creating close to a dystopic urban vision. Using terms like politically correct, he’s basically saying to that couple, “You know that your husband, frankly, didn’t get the promotion because it went to one of those other groups.”

In the rural communities, they just think they’re getting screwed by a rigged system. Which, quite frankly, they have been. I also think this is why the conversation about automation is important. When I was in more rural areas that were Trump counties, I would say, “Look, I’m as pissed off as Trump is that we’ve lost 5.7 million manufacturing jobs in the last decade. Can anyone tell me where 85 percent of them went?” And every hand in the room would go up, and they would say, “Automation,” Or, “Technology.” Or, “Robots.” I would ask the same question in the inner-ring suburbs, and people would actually say China or India.

I think the other important piece of this, though, that’s related to monopoly is economic consolidation. Here, I think, is one of the real areas that we have to address, not just politically, but because it’s a genuine policy challenge. During the Clinton recovery, 70 percent of new businesses were created in small and medium-sized towns. During this most recent recovery, 83 percent of new businesses were created in the big, urban areas, 17 percent in medium-sized towns and counties, zero percent in small towns and counties. So when people are feeling like their region is being left behind, they’re correct. We have this great sorting that’s going on right now that I think is being driven by a combination of factors, including both automation and consolidation in the economy.

Why does the Democratic Party have so much trouble addressing these voters who have been impacted by the changes you are discussing? It’s hard to avoid the sense that it has something to do with the fact that the Democrats are a multiethnic party, which immediately makes it harder for them to appeal to a working-class majority.

I think it comes back to this point: that if the lived experience you see is “this destroys your community,” is “corporations going overseas, jobs now being replaced by technology,” and you see the Democrats as the party of Silicon Valley and California and Wall Street, then it’s not hard to jump to that conclusion. We can’t get into a false choice where you hear people say, “Democrats seem to care more about where someone goes to the bathroom than whether or not my family can put food on the table.” That’s the trap we can’t let ourselves go into, because we clearly need to stand for attacks on the vulnerable, including the LGBTQ teenage group, which is one of the most at-risk groups in the country. Or what the hell are we doing this for? And at the same time, not allow ourselves to be in a place where it seems to many parts of the country that that’s the only thing we care about.

To me, the answer on that is not to go softer on civil rights and cultural issues; it’s to go stronger on economic issues. When we are very clear in that space about being the ones fighting for everyday folks, then we not only counterbalance that, but then we actually convert more hearts and minds on issues of equality.

It’s not uncommon that I would go to meet with African American leaders and have them say, “Whatever happened to the trade schools and apprenticeship programs, and those pathways into the middle class?” Then I’d be out in Trump country that afternoon, and they’d be saying, “Hey, whatever happened to the trade schools and the apprenticeship programs?” Certainly, the community college system—and someone like Mark Warner was way ahead of the curve on this—has really been a crucial part of reviving the notion that … the Democratic Party needs to be much more embracing of trade schools and apprenticeship programs and the community college system. I think there’s a lot of false correlation in the data about the importance of four-year degrees.

You are now going to focus on state and legislative races and so on. Why do you think it is that liberals seem less good at that than conservatives?

The first one that’s often overlooked is simply volume of resources. There’s long been this false sense that somehow the two sides have similar amounts of money to play with. The Republicans and conservatives are playing with such a vastly larger amount of money that they’re able to play on multiple playing fields at the same time. And they’re able to invest in groups that can take kind of the 10- or 15-year strategy. Whereas Democrats and progressives tend to end up piecing just enough together to get through the next fight.

Why is that?

A lot of it is just return on investment. For every progressive billionaire who’s out there, there are 10 on the other side. And the 10 on the other side will get back everything that they’ve spent within a single tax cut from the Bush administration or what would have been the Romney administration. You have an enormous amount of corporate money over the years bankrolling these groups for similar reasons. They get a single regulation through, and that’s paid for itself. You don’t really have the equivalent on the progressive side.

The second is a longer tradition, which is coming out of the civil rights movement. Progressives came to see states as a barrier to progress, and the federal government as the driver of that progress. But we have to remember: At other points in our history, states have been actually the laboratories of progress. It was progressive states that pushed back against the Fugitive Slave Act, and then the Alien and Sedition Acts. So I think right now we’re coming to understand what it means for California or New York to really be able to road-test a bold idea, and understanding how much we got our asses whupped in the redistricting fight a few years ago.