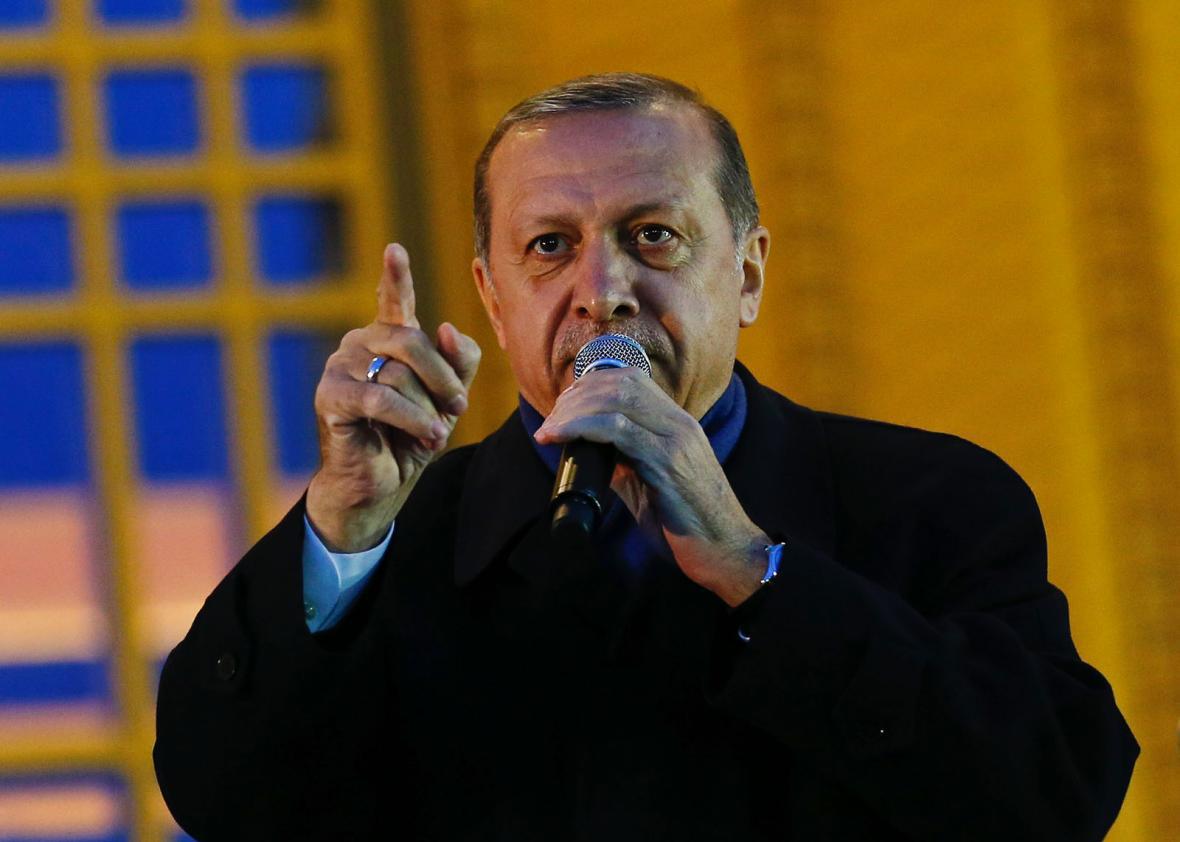

On Sunday, Turkish voters appeared to pass a referendum that granted new power to the country’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. A recount has been demanded by members of the opposition and European election observers have cited the vote’s unfairness, but Erdogan, who leads the Justice and Development Party (AKP), seems poised to tighten his grip. Turkey currently has a parliamentary system, but Erdogan is the most powerful man in the country, and since a failed coup last year, he has purged opponents from government and important institutions. Before the referendum, he undertook a campaign of intimidation against opponents who warned a “yes” vote would only further entrench his autocratic rule. (The referendum formally transfers enhanced powers to the presidency and gives the president more control over the judiciary.)

To discuss the vote and the imperiled future of Turkish democracy, I spoke by phone with Suzy Hansen, a journalist living in Istanbul who has covered Turkey for the New York Times and other outlets for many years. (Her new book, Notes on a Foreign Country: An American Abroad in a Post-American World, comes out in August.) During the course of our conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, we discussed the long-standing divisions in Turkish politics, the differences between Erdogan and Trump, and the type of autocracy Erdogan wants to establish.

Isaac Chotiner: Some analysts had speculated that a close victory for Erdogan might actually be the best result, because he would be humbled a bit, whereas if he had lost it would have meant chaos. Do you buy that optimistic reading, or is this just a complete disaster?

Suzy Hansen: I understand why someone would say it. There were a lot of people, when they were deciding which way to vote, who said, “It’s going to be a disaster either way.” And I think that is true, especially in terms of the economy because it would have been way more chaotic if it had been a ‘no’ vote. But it already is chaotic, and that’s something that isn’t being talked about as much, and I think Erdogan is going to have a really hard time fixing the economy.

But I don’t really think we can say that things are not going to be a disaster. I don’t think we really know how Erdogan is going to react because now we have a situation where he is victorious and paranoid. And I am not sure that for someone with his personality, especially with the way it has been changing in the past couple years, this will be a very good thing. We will see what happens with the people who are in jail. I think the next few weeks will be really interesting and important.

The weird thing about Turkey is that it used to be much more predictable and now everyone lives in a state of uncertainty. We don’t really know what is going to happen. Will he arrest more people or let them out of jail? Nobody really knows. He’s just become much more volatile and because everything depends on him, the state of the country depends on that. Look what he said when the European election monitors said it wasn’t a fair election. He said, “Know your place.” This is a recent development; he wasn’t always like this.

Did the size of the “no” vote surprise you?

After the vote came out, a lot of people from the United States emailed me and said, “What are they doing? How could they have chosen him again?” And in fact I thought that the vote was actually kind of amazing in terms of how many people said no. I was really quite inspired by it. In the conditions of this referendum campaign, it would have been a difficult thing to resist. There was no information, clear information, about why you should reject this constitutional package. And there was so much pressure. Basically at this point he controls and creates reality, to some degree. It really kind of feels that way. The fact that so many people were able to say no and remain independent and think for themselves is really quite incredible, and I would hope that people would realize that actually the opposition is much bigger and people are actually more displeased with this man than we have seen.

I think an interesting effect of this election will be whether or not people continue to believe in the power of their vote. If this election was in fact in some way stolen, that is an unprecedented event in Turkey’s history. Turks love elections, they vote in huge numbers, and they believe deeply in the power of their own vote. In many ways, free and fair elections were the one thing the Turks had left, in terms of their sense of the country’s democracy. And if large numbers of people come to believe that their vote didn’t count this time, then that could be tragic.

You brought up a couple things I want to go back to. For starters, what specific economic troubles were you referring to?

The tourism issue is bigger than it might seem. It’s an enormous part of the economy. But also the construction sector is slowing and so there is a whole chain. Most of the economy, which appears to have grown—everybody always talks about how the Turkish economy is so great—has been from foreign investment, and a lot of that is decreasing because of security situation.

A couple more Trump towers will solve things.

I don’t think that will help much at this point. The problem is that you hear the average person talking about how they are suffering and how times are hard, but it hasn’t been totally acknowledged here by the state. But you hear it from everybody, from the man who works at the market to very wealthy people.

How do you think Erdogan’s personality has changed?

I think a lot of people, after Trump was elected, compared them to each other. They said to me, “Now we understand how the Turks must feel and must have felt.” And I think that it is really, really, quite different. In 2007, he was a much more conciliatory person. At that time the AKP was talking about the EU, and they had made all of these EU reforms. And he himself used this very democratic language. I would say it was the language of liberalism, human rights, etc.

It was a different kind of language, and it has become much more nationalistic, and much more about Erdogan himself, and volatile and sometimes erratic. Not rational. He is really on television and the radio all the time. It has this effect of somehow convincing people of what he says because it is the only thing you are hearing. But also driving people insane. I really do think Erdogan and Trump are very different though. Erdogan has run this country pretty well for a long time.

Yeah, that is not happening here.

Erdogan knew how to be a politician and actually was a politician. He had run a city and improved services in the country to an extraordinary degree. All of these things are true. But now it’s all about whether people are pleasing him and doing what he wants. You have seen these examples of megalomania. It feels unstable.

Do you think Erdogan was always going to try and gain absolute power and the attempted coup merely sped it up, or do you think the coup fundamentally changed him and Turkey in some way?

He had a tremendous amount of power at that point and has always wanted to change the system to a presidential system. This has been his dream for a long time. But the coup was such an enormous thing. There have been four coups in Turkey’s history already. The memory of them, especially the 1980 coup, looms large in everybody’s mind. The aftermath of that coup was pretty brutal and changed the country forever. People are really aware of the impact of a military coup. And of course when we talk about what changed him, I think this fight with the Gülenists [the group Erdogan accused of launching the attempted coup] was part of it.

It probably genuinely scared him. It was from within his own state and within his own party. They had a tremendous amount of power and are very smart and very educated and have an international network. So I think when you look at the reasons why a leader would suddenly panic or become more paranoid, this is a pretty strong reason actually. What do you do after an attempted military coup, and if it is by a group that is quite large and quite influential the question of how you handle it is an interesting one that hasn’t really been addressed yet.

To what degree do you interpret this vote as a referendum on Erdogan, and to what degree do you think it was more a reflection of cleavages in Turkish society between things like religion and secularism that have been evident for decades?

That’s a really interesting question because I think the vote has been stripped of its complexity. I don’t think it is only about Erdogan. The question of “What is the world going to look like without him?” is probably a pretty scary one for some people. It’s a conservative reaction; I don’t think it’s that surprising. And there are the people who hate him. But a lot of people were also just thinking in a practical way that they like their system and why does he want to change it? That was another practical response. But there hasn’t been a really vibrant debate so I don’t know if we can talk about all the political ideas really truly being out in the mix.

One of the big things that has been missing is that the leader of the Kurdish party, Selahattin Demirtaş, has been in jail, and many other politicians have as well. And they had injected a kind of complexity and new ideas into the debate. That’s been gone. That’s one of the biggest reasons why this referendum doesn’t feel representative or fair.

What was it like in Istanbul, which narrowly voted against the referendum, over the last couple of days?

It was really surprising that Istanbul and Ankara both did. That means that some of the working classes that used to be Erdogan’s base, and used to be very faithful to him, have shifted. That’s why I think the referendum is actually quite inspiring. People were able to make an independent decision even though they were constantly being told that the world would end if they didn’t vote “yes.” In Istanbul there have been some protests but it has been subdued. It’s funny about Turkey. I was thinking about the story I wrote, and people said, “Oh it sounds so awful there.” And of course it is awful what’s happening. But day-to-day life is quite nice and you don’t feel it on the street.

How will an Erdogan with expanded powers manifest himself on the foreign stage?

We don’t know except that if he decides to take this as his mandate, he will become more defiant than he already has been. The question is the Europeans. The fact that the election monitors came out against him is not going to help. You still have the refugee issue, and this issue in the European Court of Human Rights where people are filing cases against the post-coup purges, and the Court hasn’t taken up any of those cases yet. But if they start doing that then he will take that as an attack on him, and you might have another showdown coming. But the problem is that the Europeans, as upset as they are about Turkey and Erdogan, are not going to do anything as long as there is this refugee problem. And that is what has frozen foreign relations in a lot of ways.

The original fear about Erdogan was that he was going to be an Islamist, and the question was whether Islamism and democracy were compatible. Is your fear now Islamism, or rather that Erdogan will just be a typical strongman, of the type that lots of countries have had and Turkey has had under previous military rule?

I think he is new. I think that the only reason that he could have assumed so much power was that there was a system in place that allowed for it. Some of the liberals and leftists who supported him in 2007 might have thought the institutions were strong enough in Turkey to withstand one very powerful leader or party and that turned out to be not the case. And I think in many ways he is acting like the military generals of the past. However, in terms of the amount of power that he has, the lack of diversity in the media and control in the economy and just, again as I said, this sense of creating reality, does feel new. And the fact that Turkey has become a wealthier country—whereas it used to be very, very poor—has brought him more power, and is a really new thing.

OK, but do you see him entrenching an Islamist autocracy—there had been fears that he would do things like make women wear headscarves—or a more generic autocracy?

I think that it is really interesting that that was the fear. And it was such an enormous fear, obviously. And a lot of those things that people feared in the beginning haven’t happened. Nobody is being forced to wear headscarves. Now, of course there is a different kind of effect when you have the leaders of the country behaving in outwardly religious ways or using religion in speech, and I think people feel that.

But the problem is that people still have those fears about headscarves and making the country more Islamic. I think that is coming back. You see people feeling nostalgic for Atatürk more than ever. Women especially will always have that fear, and when I ask about it now, they will remind you of the fact that there has always been this long history of political Islam in Turkey. Erdogan was not the first, and there have been many different kinds of Islamic brotherhoods and movements which have been trying to figure out how to gain power. And so there is a feeling of: this is a long time coming and we don’t really know what he might impose or might desire.

I would still say it has been 15 years and if he really wanted to make all those changes, considering all the power he has, he would have. But for me personally, the fear is not an Islamist dictatorship. I don’t really know what that would look like. It’s more the increased power. He is controlling the media, and having a huge impact on academia; imagine all the ways in which the society is changing from one view being constantly presented to people. A lot of diversity is being squashed in ways we aren’t even seeing right now. The nature of the country will change because of that.

But I don’t want to discount the fears of a lot of Turks because they have their reasons for having those fears. And I think that a lot of people didn’t listen to them in 2007, and It’s possible that that opposition in 2007 did see something in him that everyone else didn’t.