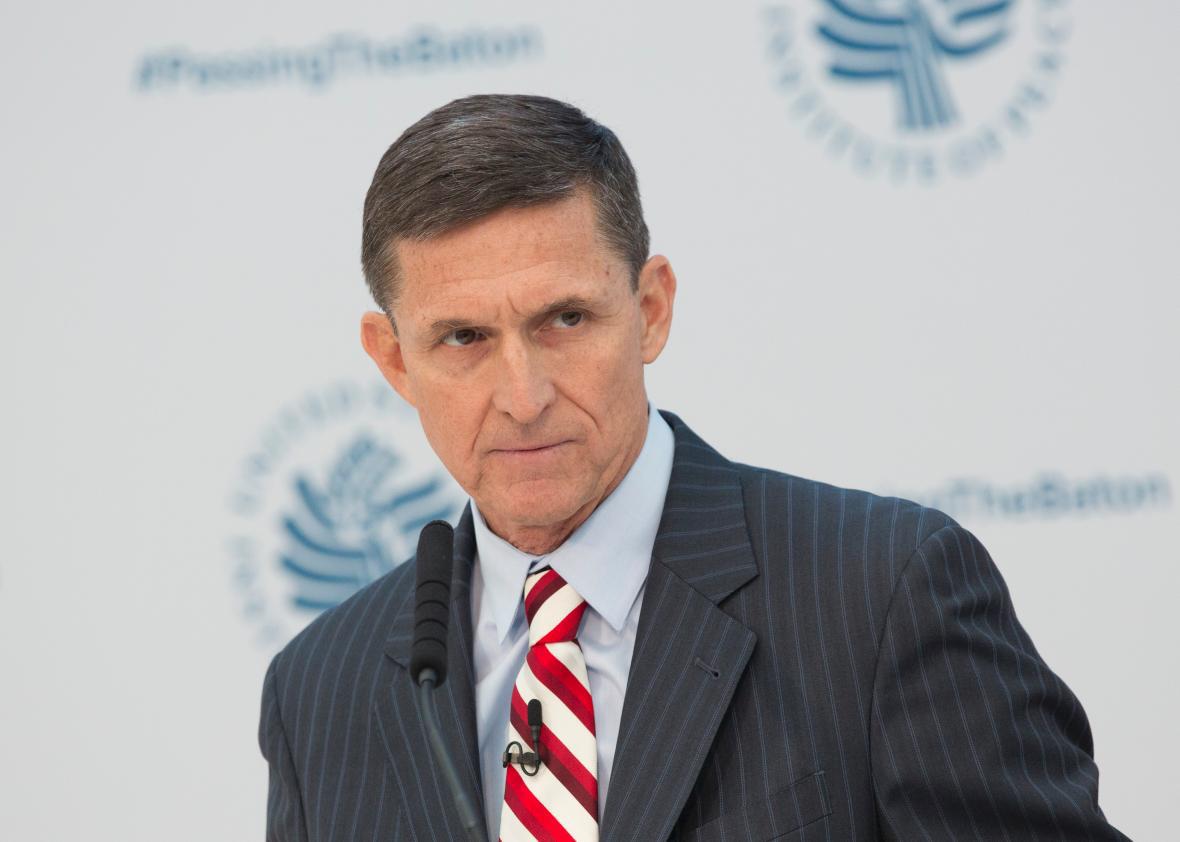

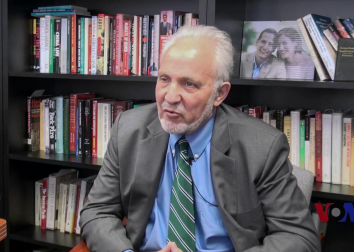

The resignation of National Security Adviser Michael Flynn this week was a stunning development, even for an administration that has generated more chaos and upheaval than Washington has ever seen in the early weeks of a presidency. With breaking news arriving nearly every hour, and with American foreign policy in an uncertain state, I spoke on the phone with James Mann, a journalist, expert on foreign affairs, and author of The Obamians: The Struggle Inside the White House to Redefine American Power.

During the course of our conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, we discussed what made Flynn such a unique national security adviser, whether the “deep state” is trying to undermine Trump, and the most boring part of the president’s job.

Isaac Chotiner: You wrote a piece for the New York Times in December arguing that Trump’s foreign policy team was built to fail. What has surprised even you about the past month?

James Mann: I have been surprised by the intensity of the fights over Flynn, and I have been surprised at what it produced within the administration, which is to say: intense skirmishing among high-level people at the White House. To be self-critical about that piece, probably what I had more in mind and sketched out was a clash between Flynn and the secretary of defense, James Mattis.

How different was Flynn’s brief tenure compared with people who have held his job?

Usually what happens is that a president-elect, early on, designates a national security adviser who then begins a fairly orderly process of putting together a staff. And actually, Flynn followed some of these precedents, staffing out a National Security Council. It was different in that it was heavily dominated by people from the military. But there were also three things that were different about Flynn.

The first was an intense regional focus on the Middle East and ISIS and terrorism. Flynn had no particular experience in dealing with other parts of American foreign policy or national security. Let’s remember that Flynn’s development of ties with Russia came from his efforts to work with Russia on the Middle East. Even Russia was seen through a Middle Eastern focus. That is very unusual, for a national security adviser to be that focused in a way that everything else is seen through that lens.

He has Muslims on the brain.

Yes. [Laughs.] The second was a bureaucratic animus. He had it in for the regular intelligence community. Whatever grievances he had, he wore them on his sleeve. There were two different grievances. One was in favor of the guys in field versus the people in Washington, and the other grievance was against the CIA. Those are old fights, and a national security adviser doesn’t usually bring those to his new job. The third is the matter of temperament, which isn’t totally unrelated to the bureaucratic animus. This is a guy who exuded anger in a way that past national security advisers didn’t. And fourth, I would add, is an almost cheerleader quality for the president-elect. There is really no precedent I can think of for a national security adviser having stood up at a political convention and suggesting that the opposing candidate should be locked up.

One of the surprises is that all of this is taking place without all that much input from the secretaries of state and defense. This is really a very narrow bureaucratic battle in which two or three of the leading figures in the bureaucracy seem to play little of a role. What I am used to, much more often, is a full-scale, all-out war between the leading Cabinet secretaries, which was true in the Reagan administration and under George W. Bush. Or a battle between the national security and the online policy makers.

What do you mean by that?

Meaning the people carrying out the policy with China or Russia day to day. What’s amazing is that Flynn never got to the questions that should have hit him about how operational he should be—should he be in what is normally called the Brent Scowcroft model, where the national security adviser is sort of the arbiter? As an aside, even Scowcroft didn’t follow that model, but it is the ideal that often gets put out there.

When have national security advisers departed from that ideal?

The first national security adviser to really break that mold was [Henry] Kissinger. In my mind, the single moment that was the most humiliating that you could possibly imagine for a secretary of state came as Kissinger was leaving on his secret trip to China, and they hadn’t even told Secretary of State [William] Rogers that he was going. First they told him a lie, which was that this came up quickly as he was leaving for Pakistan. Then someone felt guilty, and they sent Kissinger’s deputy, who was Alexander Haig, to inform Rogers that, oh yeah, Kissinger has been negotiating with the Chinese, and has also been conducting secret talks with the North Vietnamese in Paris, and talks on arms control.

Were you surprised by the amount of opposition Flynn and the president have faced from the bureaucracy?

I guess I am not all that surprised. It would be one thing if Trump was just trying to change policy, but he is trying to change policy while belittling the motives and sincerity and patriotism of everyone before him. Flynn and Trump were impugning the motives of the entire U.S. intelligence community, and in the case of Flynn, he was telling untruths, which people in the intelligence community had access to. And they had legitimate access to it. I can’t believe the back-and-forth about monitoring these phone conversations. They weren’t monitoring Flynn; they were monitoring the Russian ambassador. And above all, you had the perception that Flynn’s untruths might be, in the view of some in the intelligence community, betraying the interests of the United States to an adversary.

Does the extent of the leaks worry you? People are using phrases like deep-state coup.

I find those fears overblown. This is a unique case in which someone at the level of the national security adviser was saying things that were not true about his conversations with the government of one of the United States’ two leading adversaries in the world. The fact that people within the bureaucracy wanted to come out—I don’t see that as all that worrisome. I certainly don’t see it as something like a deep-state coup, in your words.

How likely is it that Trump will make a major effort to staff multiple levels of the bureaucracy with allies, and how possible is that for him to pull off?

I think he is going to try. I think that is possible, if he is willing to find people who are willing to deal with Congress and the press and other governments in something other than an angry and conspiratorial way. Anything lower down requires experience with policy areas, whether it’s a country or region or an area like proliferation or counterterrorism. Most of the people in those policy areas have a body of knowledge, which Trump seems to mistrust. If there is a resentment of all expertise, then it is hard to get experts.

Why can’t he staff these positions with Stephen Miller and Steve Bannon types?

The problem is that those nonexperts are going to have trouble winning support from the congressional committees, which know a little bit about the areas they are working on; from foreign governments that may know about the Middle East or Asia a little more; from journalists who cover particular areas. You won’t have a policy if you don’t have people who can draw up a policy.

Along the lines of what you were saying earlier, it’s interesting that the person tapped to be the next national security adviser, Robert Harward, is supposed to be very close to Mattis.

Exactly, yes.

Maybe things will start running more smoothly.

It could hardly run less smoothly. Let me add on that: By the natural order of things, foreign policy is still moving forward. It has to. Like with [Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo] Abe’s visit last weekend, you can envision a scenario—maybe for good reasons, more likely for ego reasons—where Trump begins to like having foreign leaders come either as supplicants or bringing money and investment. He might get into at least the summit aspect of it. You can envision things settling down and that he might somehow get some pleasure out of the routine aspects of high-level diplomacy.

On the other side of that, and I have heard this from Obama officials and in general, a good part of a president’s job is going to high-level multilateral meetings. There is a wonderful anecdote where during the Trump-Obama meeting, Obama just said he was going to go to APEC [the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum], and Trump asked what it was. Obama described it, and Trump said, “That sounds boring.” And in fact some of those meetings are. Obama himself used to get annoyed at some of those meetings he had to sit through, with four hours of speeches, while his top aides went off into bilateral meetings on topics that might be more interesting. He would be left there. It’s not clear to me how [Trump] is going to get out of those, but I don’t see him sitting through long meetings. But I can see him enjoying, eventually, well, I don’t know.

None of us really know, unfortunately.

[Laughs.] Yeah.