On Thursday, citizens of the United Kingdom will vote on the so-called Brexit: the momentous question of whether the country will leave the European Union. The referendum was set by the Conservative prime minister, David Cameron, who wants to “remain” in the EU but who also leads a divided party in which major figures (including Boris Johnson, the former mayor of London) are on the leave team. Also split is the Labour Party, although its new leader, Jeremy Corbyn (himself long skeptical of Europe) has joined the vast majority of the British establishment—from the Bank of England to most large businesses—in arguing for the status quo.

The case for Brexit has been driven in large part by a fear of immigration, especially from Eastern Europe. And although the vast majority of economists are opposed to the idea of leaving the EU, believing that it could potentially have worldwide economic effects, polls currently show a close vote. If Brexit passes, expect a major shake-up in both parties, a new prime minister, and a completely unknown future for both Britain and Europe. (Also uncertain is how the tragic murder of the pro-Europe, pro-immigration Labour MP Jo Cox, apparently at the hands of a neo-Nazi, will affect the vote; regardless, her death has drawn attention to the stridency of the campaign and the frequently hateful and bigoted nature of the leave side’s propaganda.)

To discuss the Brexit vote, and rising populism around the world, I spoke by phone with David Runciman, a professor politics and international studies at Cambridge and the author of The Confidence Trap: A History of Democracy in Crisis From World War I to the Present. During the course of our conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, we discussed the similar factors behind Donald Trump’s rise and the pro-Brexit movement, the poisonousness of intraparty conflict, and why the referendum may not really settle larger questions about Britain’s place in the world.

Isaac Chotiner: How much do you see the prospect of Brexit as something very specific to Britain, and how much do you see it as something that’s affecting many countries right now: a crisis of confidence in institutions and elites?

David Runciman: I don’t think you could make sense of it by thinking it’s just something going on in this country. It’s partly about Europe, but it’s not primarily being driven by specific U.K.-based concerns about the relationship between Britain and the European Union. It’s being driven by a loss of confidence among a significant portion of the voting population in institutions, and that includes political parties. It’s the kind of political event that doesn’t fit our party structure, and it also chimes with what’s been happening in America, which is that there is a feeling that the old rules don’t really apply anymore.

What do you think is driving this larger crisis of confidence?

Some of it has to do with a breakdown in the relationship between voters and political parties. What you’re seeing in the Brexit campaign is a kind of frenetic version of this, which is party leaders frantically looking for a way to tell their supporters to do what they want them to do. Their supporters are just rebelling, and they’ve lost the language, they’ve tried all of the conventional routes, to signal to their supporters that it really matters.

I think it parallels the United States in the sense that two-party systems, which we have and you have but most of Europe doesn’t have, can’t accommodate the range of opinion and the big divides in British political life that don’t fit the party divides. The big divide is the kind of cosmopolitan, metropolitan, urban people on one side and not just sort of rural or traditionalists but the wide range of people who feel left out.

Obviously there are a lot of Trump similarities there, from his unwillingness to fit with either party’s more coherent ideology to the lack of success elites have had signaling about him.

Exactly. We don’t have a Trump, but what we do have is what you describe, which is the big divisions that are driving this whole thing. Party leaders are flailing around, and just when they think they’ve got a message that works for one part of their constituency it alienates another. When Jeremy Corbyn says something that appeals to his well-heeled metropolitan supporters, he pisses off traditional working-class Labour supporters. If he says anything about immigration that appeals to them, he seriously alienates his liberal supporters in the city.

To turn to specific issues, what is driving Brexit? Is it mainly immigration?

In the background is the sense that this is a very dangerous world and that things are happening around the edges of Europe that if uncontrolled would be overwhelming. There’s a racial element to it as well, but the primary driver of it is people’s either real or perceived experience of immigration from Eastern Europe. The sense that European Union rules allow large numbers of people from Eastern Europe to come to Britain. The word that’s coming back from the parts of the U.K. which are strongly for “leave” is that people feel that access to housing, to jobs, and to public services is being squeezed by Eastern European migration.

That seems to be the primary driver of it, and it’s not all scaremongering. There is some basis in fact that the numbers of Eastern European migrants has been very high, but it’s not the case that the places where it’s highest are the places where people are most against remaining in the U.K. As always with these things, there’s often more fear of it in the places that are nearby than in the places where it’s really happening. That’s the primary driver, and some of the secondary stuff is about Syria and also terrorism, and it’s a pretty toxic mix.

What has been the counterargument to all this, much of which has contained a lot of demagoguery and fearmongering?

The people on the “remain” side have been trying to make a case based on the likely economic consequences driven by experts, economists, the Bank of England, the [International Monetary Fund], and so on, telling people that they would be crazy to risk Brexit, and that hasn’t been working. At the same time the people on the “leave” side have a message, which is simpler and connects about immigration. In a sense it’s the failure of the economic message to get any purchase because of people’s suspicion of being told by bankers what to do. You could say the simplest explanation for this is that in politics something beats nothing and the “remain” campaign has been nothing.

Do you think there’s a way in which bankers telling you that the economy’s going to do badly if you vote “leave” is not only ineffective but counterproductive?

Yes, probably. If you are suspicious of Europe and of finance and of globalization, being told by Christine Lagarde that she knows your interests better than you do is unlikely to work.

Obama came over and did the same thing.

He did say the same thing. It was meant to be him telling us what he really thought. He used this word queue, saying Britain will go to the back of the queue, not to the back of the line, which made people who care about these things notice that this was contrived, that it’d been scripted for him by the Brits because queue is our word not your word. That’s the kind of motif of the ways in which it looks to the people who are suspicious of elite conspiracies, which doesn’t mean that the things Obama was saying weren’t true. I suspect they were true, I suspect he believes them as well, but the messaging has been bad.

How do you think both the post-2008 economic crisis and Europe’s response to it have played into the Brexit campaign?

That’s the really complicated question, because most British people think, “Thank God we never joined the euro.” I think most people in Britain also had a kind of vague memory that elites, including the party leaderships, particularly the Labour party leaderships were very keen for us to join the euro and that often we were told we needed to join the euro or terrible things would happen. Now they realize that terrible things would have happened if we’d joined. People in Britain sense that they do not want to be dragged anywhere further into that mess. I don’t think British people feel particularly that they’re on the hook for Greece or that what we’ve had to do bail out southern Europe or parts of Europe. I think it’s more a fear of the possibilities of contagion and the more distance we can put between Britain and the mess that might be coming, the better. It’s as vague as that.

I suppose there’s a feeling that European institutions since the financial crisis haven’t done much to make the people of Europe have confidence in them. Certainly compared to the U.S., Europe’s recovery has been weak. All of the talk now, which is that to vote to leave might unravel the European project because it’s so fragile, is counterproductive. It makes people think, Well if it’s that fragile, we should get out.

If Brexit succeeds, how do you see British democracy or British institutions changing?

I don’t think there’s a good outcome here. If Brexit succeeds, I don’t think the immediate impact will be felt by people in the sense that there will be a massive run on the pound or people will suddenly notice that they’re poorer. I think the immediate impact would be on politics and party politics: The two main parties will find it very difficult to hold together.

The really kind of interesting question is: If the British people, in a referendum, vote to leave, one of the things they’re doing is reasserting the sovereignty of the British parliament, which you know that’s part of the argument here, that British sovereignty has been sacrificed to European institutions, so they’re saying, “We want to take sovereignty back to parliament.” Parliament is massively in favor of remaining in the EU; there would be an overwhelming majority if you had a vote in parliament to stay. The institution whose sovereignty is being asserted doesn’t want to leave, so that’s going to be chaotic I think, and the immediate consequences will play out in party leaders falling. Cameron won’t last long, Corbyn won’t last long, and British politics will be reconfigured. If the idea is that by leaving we will restore confidence in British institutions, by leaving we’ll put much more pressure on British institutions, and probably they’ll start to creak.

And if you stay?

The difficulty is that the safest bet is that it’s going to be close, so a large number of people are going to have voted to leave, and I think they will feel with some justification that every single weapon of the British state had been deployed to try and persuade them otherwise: the Bank of England, the Civil Service, all the party leaders, current prime ministers, former prime ministers Tony Blair, John Major, all these people, the Scottish party leaders, everyone has been wheeled out, the entire apparatus of the British state has been deployed to kind of stifle them. If still 48 percent of people voted to leave the key question for British politics would be, “Who’s going to speak for those 48 percent?” Because all of the main parties will have been on the other side. You have half of the voters who will need representation, and again I think that’s going to be very messy.

It could equally lead to the main parties splitting. There has been a lot of bad blood in this campaign. It’s definitely, in my lifetime, been the most personally vicious campaign. You see it with the Republican Party, right? When the big divisions are inside political parties it’s more personal, and there’s a much stronger feeling of betrayal. Yeah, Democrats hate Republicans, and Republicans hate Democrats, but people can live with that. When Republicans hate Republicans or when conservatives hate conservatives, that bad blood can last for decades.

How big will a “leave” vote be for Europe?

If we leave, I think almost certainly there will be some trigger effects around Europe. It’s hard to see other countries simply bracketing off Britain and saying, “That was just a special British case.” There’ll be equivalent demands in other parts of Europe, but if we vote to stay the elites will be very relieved across Europe. The other thing is that the British people are being told by the leaders of all the European governments to stay. The people who feel betrayed by elites are not going to feel that a British vote to stay has reinforced the legitimacy of their belief, they’re going to feel that it’s just another reason to be suspicious.

We’re in a really tight bind here, and I think it is equivalent to some of the things going on in the U.S. with your presidential election. It’s hard to see the outcome that kind of re-calibrates the system so that people feel it’s working again. If Hillary wins, it’s a bit like us voting to stay in.

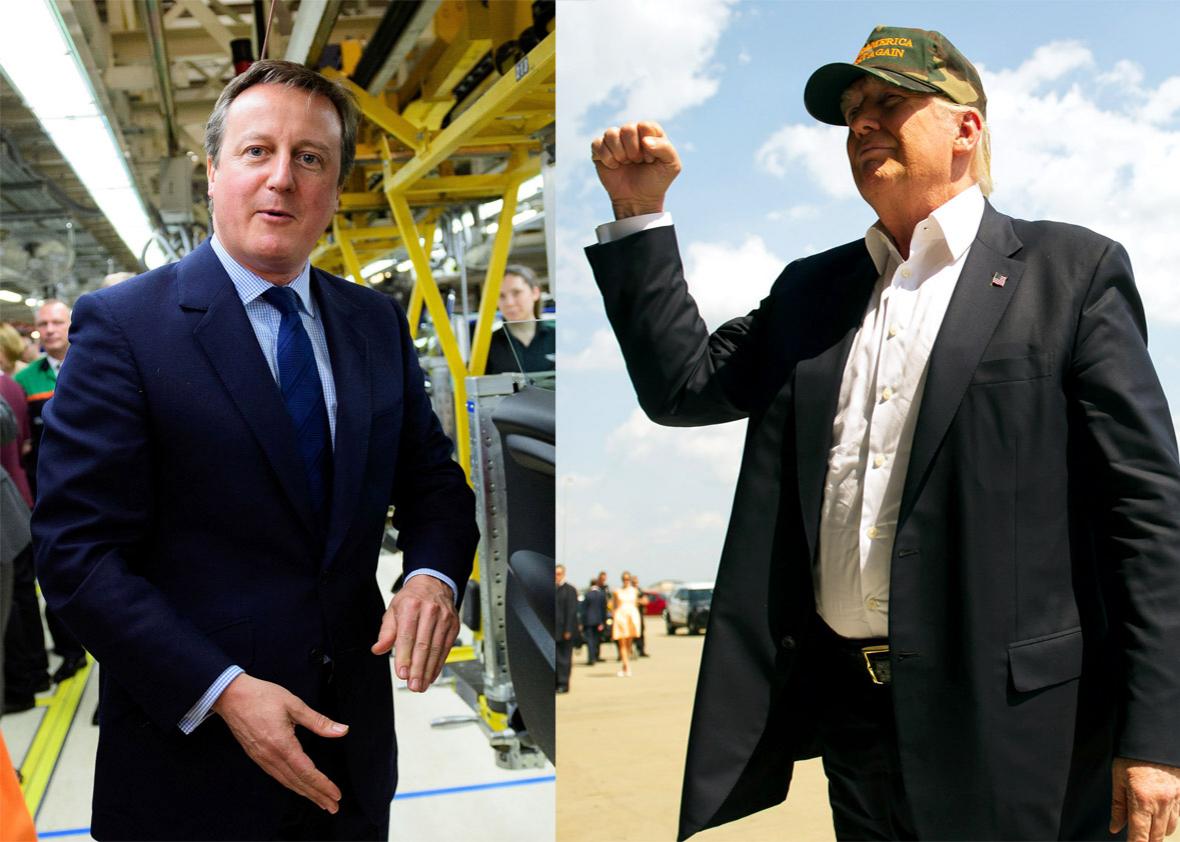

Right. You have Hillary Clinton and David Cameron, who I don’t think are the most impressive embodiments of the American and British establishments, and yet they both appear at this crazy moment like they are all that stands between us and everything falling apart.

Yeah, exactly. That’s the feeling about it. Cameron came close to something pretty disastrous with the Scottish referendum, but he got away with it. He came through our general election that he was not expected to win. If he gets through this one people won’t conclude that therefore he’s a very successful politician; they will just think he’s incredibly lucky. And so your democratic legitimacy is founded on the idea that you get away with it each time, and at some point someone’s not going to get away with it. Maybe not here, maybe not in your general election, maybe in the French general election, who knows, but it’s hard to see over the next two to three years that the luck is going to hold, because it’s not as though the economic situation is looking particularly rosy. At some point someone’s luck is going to give out and it might be this month.

I definitely hope it’s not in November.